Definition/Description

Cervical myelopathy refers to compression on the cervical spinal cord. Any space occupying lesion within the cervical spine with the potential to compress the spinal cord can cause cervical myelopathy.[1][2] Cervical myelopathy is predominantly due to pressure on the anterior spinal cord with ischaemia as a result of deformation of the cord by anterior herniated discs, spondylitic spurs, an ossified posterior longitudinal ligament or spinal stenosis[3]

The spontaneous course of myelopathy is characterised either by long periods of stable disability followed by episodes of deterioration or a linear progressive course. The presentation of a cervical myelopathy varies in accordance to the severity of the spinal cord compression as well as its location.[4]

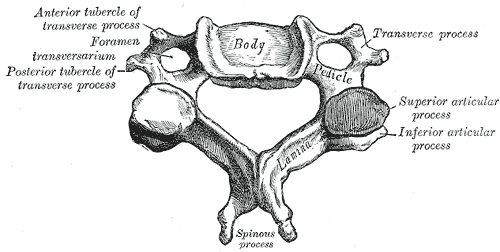

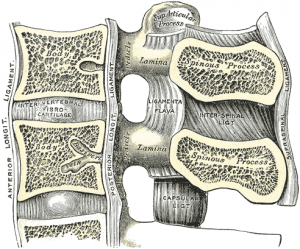

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

There are seven cervical vertebrae and eight cervical nerve roots.[2][5] The spinal cord is the extension of the central nervous system outside the cranium. It is encased by the vertebral column and begins at the foramen magnum.[6] The spinal cord is an extremely vital part of the central nervous system, and even a small injury can lead to severe disability.[7]

A complex system of ligaments serves to stabilise and protect the cervical spine. For example, ligamentum flavum extends from the anterior surface of the cephalic vertebra to the posterior surface of the caudal vertebra and connects to the ventral aspect of the facet joint capsules. A ligament that is often involved in this condition is the posterior longitudinal ligament. It is situated within the vertebral canal, originating from the body of the axis, where it is continuous with the tectorial membrane, and extends along the posterior surfaces of the bodies of the vertebrae until inserting into the sacrum.[7]

Chronic cervical degeneration is the most common cause of progressive spinal cord and nerve root compression. Spondylotic changes can result in stenosis of the spinal canal, lateral recess, and foramina. Spinal canal stenosis can lead to myelopathy, whereas the latter two can lead to radiculopathy.

Epidemiology

Cervical spondylotic myelopathy is the most common disorder of the spinal cord in persons older than 55 years of age.[5][8][9] Radiologic spondylotic changes increase with patient age – 90% of asymptomatic persons older than 70 years have some form of degenerative change in the cervical spine. Cervical spine myelopathy resulting from sagittal narrowing of the spinal canal and compression of the spinal cord is present in 90% of individuals by the seventh decade of life.[10] Both sexes are affected equally. Cervical spondylosis usually starts earlier in men (50 years) than in women (60 years). It causes hospitalisation at a rate of 4.04 per 100,000 person-years.[5][11]

Pathological Process

The causes of cervical myelopathy can be divided into different categories:

- Static factors: A narrowing of the spinal canal size commonly results from degenerative changes in the cervical spine anatomy (cervical spondylosis) such as disc degeneration, spondylosis, stenosis, osteophyte formation at the level of facet joints, segmental ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament and yellow ligament hypertrophy, calcification or ossification. Patients with a congenitally narrow spinal canal ([4][10][11][12]

- Dynamic factors: Due to mechanical abnormalities of the cervical spine or instability.[4]

- Vascular and cellular factors: Spinal cord ischemia affects oligodendrocytes, which results in demyelination exhibiting features of chronic degenerative disorders. Glutamatergic toxicity, cell injury and apoptosis may also occur.[4]

Cord compression is thought to be a combination of static compression and intermittent dynamic compression from cervical motion (flexion/extension).

Characteristics and Clinical Presentation

Cervical myelopathy can cause a variety of signs and symptoms. Onset is insidious, typically in persons aged 50-60 years.

The symptoms usually develop slowly. Because of the lack of pain, there may be an interval of years between the onset of disease and first treatment. Early symptoms of this condition are ‘numb, clumsy, painful hands’ and disturbance of fine motor skills.[4] Weakness and numbness occur in a non-specific/non-dermatomal pattern. As spinal cord degeneration progresses, lower motor neuron findings in the upper extremities, such as loss of strength, atrophy of the interosseous muscles and difficulty in fine finger movements, may present.

Additional clinical findings may include: neck pain and stiffness (decreased ROM, especially extension), shoulder and scapular pain, paresthesia in one or both arms or hands, signs of radiculopathy, Babinski and Hoffman’s sign, ataxia and dexterity loss.[5][13][14] Typical neurological signs of long-tract involvement are exaggerated tendon reflexes (patellar and achilles), presence of pathological reflexes (e.g. clonus, Babinski and Hoffman’s sign), spastic quadriplegia, sensory loss and bladder-bowel disturbance.[12]

Once the disorder is diagnosed, complete remission to normality never occurs and spontaneous temporary remission is uncommon. In 75% of the patients, episodic worsening with neurological deterioration occurs, 20% have slow steady progression, and 5% experience rapid onset and progression.[4]

Common Symptoms

- Distal weakness

- Decreased ROM in the cervical spine, especially extension.

- Clumsy or weak hands

- Pain in shoulder or arms

- Unsteady or clumsy gait

- Increased reflexes in the lower extremities and in the upper extremities below the level of the lesion.

- Numbness and parasthesia in one or both hands

- Radiculopathic signs

Diagnostic Procedures

A detailed and thorough neurological examination plus MRI is the current standard to diagnose the presence of cervical myelopathy.

Plain radiographs alone are of little use as an initial diagnostic procedure. A magnetic resonance image (MRI) is considered the best imaging method for confirming the presence of spinal canal stenosis, cord compression, or myelomalacia, elements germane to cervical spine myelopathy. MRI of the cervical spine can also rule out spinal cord tumours.

An MRI is most useful because it expresses the amount of compression placed on the spinal cord and demonstrates relatively high levels of sensitivity and specificity[5][13]. Anterior-posterior width reduction, cross-sectional evidence of cord compression, obliteration of the subarachnoid space and signal intensity changes to the cord found on MR imaging are considered the most appropriate parameters for confirmation of a spinal cord compression myelopathy[5]. More than half of patients with cervical spine myelopathy show intramedullary high signal intensity on T2-weighted imaging, mainly in the spinal gray matter[15]. Radiographic cervical spinal cord compression and hyperintense T2 intraparenchymal signal abnormalities (MRI) correlate well with the presence of myelopathic findings on physical examination[16].

Clinical Examination

The diagnosis of CSM is primarily based on the clinical signs found on physical examination and is supported by imaging findings.[8] According to Cook et al,[17] selected combinations of the following clinical findings are effective in ruling out and ruling in cervical spine myelopathy. Combinations of three of five or four of five of these tests enable post-test probability of the condition to 94–99%:

- gait deviation

- +ve Hoffmann’s test

- inverted supinator sign

- +ve Babinski test

- age 45 years or older

Other clinical examination tests often used for myelopathy include:[5][8]

Although these tests exhibit moderate to substantial reliability among skilled clinicians, they demonstrate low sensitivity and are not appropriate for ruling out myelopathy. One method used to improve the diagnostic accuracy of clinical testing is combining tests into clusters. These often overcome the inherent weakness of stand alone tests.[5][17]

Outcome Measures

Differential Diagnosis

Management

There is no consensus about the treatment of mild and moderate forms of cervical myelopathy. Surgical treatment has no better results than conservative treatment over two years of follow-up[20]. Patients with cervical myelopathy that are treated with a conservative approach (anti-inflammatory medication and physical therapy) may have some short term benefit in relief of painful symptoms. Because the condition is degenerative and progressive, slow and continued progressive neurologic deterioration will occur.

Medical Management

People who have progressive neurologic changes (such as weakness, numbness or falling) with signs of severe spinal cord compression or spinal cord swelling are candidates for surgery. Patients with severe or disabling pain may also be helped with surgery.[21] When myelopathy is caused by factors of a progressive nature, such as spinal cord tumors, surgical treatment is likewise indicated[22][23].

People who experience better surgical outcomes often have these characteristics:

- The symptom of an electrical sensation that runs down the back and into the limbs

- Younger age

- Shorter duration of symptoms

- Single rather than multiple areas of involvement

- Larger areas available for the cord

The principal aim of surgery for cervical myelopathy is decompression of the spinal cord. Surgical techniques include multi-level discectomies or corpectomies with or without instrumented fusion, laminectomy with or without instrumented fusion or laminoplasty[4]. Surgical decompression is generally considered if the symptoms affect daily life, but early surgical intervention is thought to be more effective. Therefore, early detection may be the key to minimise postoperative degeneration[15].

Final outcomes from the surgery vary. Typically, one-third of patients improve, one-third stay the same, and one-third continue to worsen over time, with respect to their pre-surgical symptoms[9][21]

Physical therapy management

Patients can be treated conservatively. Kadaňka et al. found no difference in long term outcomes (2 years after the intervention) between patient who received conservative or surgical treatment[24] (LoE 2B). Even after 10 years, there were no differences found between the surgery and conservative group[25] (LoE2B). Fouyas et al also confirmed these findings. [26] (LoE1A) The only prognostic factor in which surgery can be generally recommended is with a circumferential spinal cord compression seen on an axial MRI.[27] (LoE2B)

Rhee JM et al. describes myelopathy as a typically progressive disorder and that there is little of evidence that conservative treatment halts or reverses its progression. So they recommend routinely not prescribing non-operative treatment as the primary modality in patients with moderate to severe myelopathy.[28] (LoE 1A)

The goals of physiotherapy treatment are: [4] ( LoE5)

- pain relief

- to improve function

- to prevent neurological deterioration

- to reverse or improve neurological deficits

Cervical myelopathy can be treated symptomatically. Possible therapies include:

- Cervical traction and manipulation of the thoracic spine: useful for the reduction of pain scores and level of disability in patients with mild cervical myelopathy. Other signs and symptoms, such as weakness, headache, dizziness, and hypoesthesia, can also be positively affected[29] ( LoE4). Cervical traction can be combined with other treatments like electrotherapy and exercises. Joghataei et al. reported a significant increase in grip strength after 10 weeks of this combined treatment[30](LoE1B)

- Manual therapy techniques: used to reduce the neck pain with natural apophyseal glides and sustained natural apophyseal glides for cervical extension and rotation[21](LoE5) Manipulation and mobilisations can be effective when they are combined with exercise therapy. When you use them without exercises, there is only poor evidence that it could be effective[31](LoE5)[32](LoE1A).

- Exercises: the effects of exercise therapy specifically on cervical myelopathy have not been studied, but there is evidence for exercises for mechanical neck pain. For example: stretching, strengthening exercises, active range of motion exercises, home exercise programmes[26] (LoE1A)

- Cervical stabilisation exercises: when there is anteroposterior instability of the vertebral bodies of a degenerative nature, vertebral segment stabilisation of the cervical spine can be performed with a pressure biofeedback unit (PBU),[21].(LoE5)

- Dynamic upper and lower limb exercises (flexion and extension) with the use of the PBU on the neck.[21](LoE5)

- Proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation: for the upper and lower limbs.[21](LoE5)

- Improve posture

- Motor training programmes may improve arm and hand functioning at function and/or activity level in cervical spinal cord injured patients[33](LoE1A).

- Mobility and proprioception exercises

- Aerobic exercises [21](LoE5)

- Balance training e.g. standing on one leg with eyes open and evolving to eyes closed; standing on a stable platform and evolving to an unstable platform with a rocker board [21](LoE5)

- Core stability exercises [21](LoE5)

In surgical cases, the physiotherapist still has an important role, both before and after the surgery. In the pre-operative phase, the physiotherapist needs to become thoroughly familiar with the patient’s history and about their activities of daily living that they are aiming to return to. The physiotherapist will inform the patient about the treatment program and the expectations after the surgery. There are different tests to develop a thorough picture of the patient’s baseline pre-operative status such as walking tolerance, Neck Pain and Disability Scale, Neck Disability Index and lung function. Nomura et. al found that the maximum voluntary ventilation should significantly increase after surgery[34] (LoE2B).

Exercises to improve mobility and proprioception are given to the patient. The patient starts with unencumbered stabilisation exercises and then progresses to more active mobilisation exercises. During the day the patient is encouraged to perform their usual ADLs. Intensity of the exercises is increased the following day and are progressed to include standing and walking exercises. Assuming typical progress with rehabilitation, the patient can go home after the ninth day. Physiotherapy continues in the home environment with active exercises and the ability of the patient to perform their normal ADLs is monitored, whilst increasing the intensity of the exercises as appropriate.

If there are no completions with rehabilitation, there are no recommended limitations with normal ADLs for the patient. Posture education is an important aspect[35](LoE5)[36] (LoE4)

Presentations

Case Studies

Clinical Bottom Line

Cervical myelopathy is the result of spinal cord compression in the cervical spine and is a common disorder in persons older than 55 years of age. Cervical compression in myelopathy is predominantly due to pressure on the anterior spinal cord with ischaemia and to deformation of the cord by anterior herniated discs, spondylitic spurs or an ossified posterior longitudinal ligament. Early symptoms of this condition are ‘numb, clumsy, painful hands’ and disturbance of fine motor skill. The diagnosis of cervical myelopathy is primarily based on the clinical signs found on physical examination and is supported by imaging findings of cervical spondylosis with cord compression. Once the disorder is diagnosed, complete remission to normal fucntion never occurs and spontaneous remission is uncommon. Exercises and techniques that may help relieve symptoms of cervical myelopathy include: cervical traction, manual therapy techniques, proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation, cervical stabilisation exercises and dynamic upper and lower limb exercises.

References

- ↑ Richard K. Root Clinical Infectious Diseases: A Practical Approach, 1999

- ↑ 2.02.1 Kong LD, Meng LC, Wang LF, Shen Y, Wang P and Shang ZK. Evaluation of conservative treatment and timing of surgical intervention for mild forms of cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Exp Ther Med. 2013 Sep;6(3):852-856.

- ↑ Dai L, Ni B, Yuan W and Jia L. Radiculopathy after laminectomy for cervical compression myelopathy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998 Sep;80(5):846-9.

- ↑ 4.04.14.24.34.44.54.64.7 Boos N and Aebi M (Eds). Spinal disorders: Fundamentals of Diagnosis and Treatment. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. 2008.

- ↑ 5.05.15.25.35.45.55.65.7 Cook C, Brown C, Isaacs R, Roman M, David S and Richardson W. Clustered clinical findings for diagnosis of cervical spine myelopathy. J Man Manip Ther. 2010 Dec; 18(4): 175–180.

- ↑ Cramer GD and Darby SA. Basic and Clinical Anatomy of the Spine, Spinal Cord, and ANS. 2nd Edition. Elsevier 2008.

- ↑ 7.07.1 Selzer ME and Dobkin BH. Spinal Cord Injury (American Academy of Neurology Quality of Life Series). Demos Medical Publishing (New York). 2008

- ↑ 8.08.18.2 Amenta PS, Ghobrial GM, Krespan K, Nguyen P, Ali M, Harrop JS. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy in the young adult: a review of the literature and clinical diagnostic criteria in an uncommon demographic. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2014. 120:68-72.

- ↑ 9.09.1 Kadanka Z, Bednarík J, Vohánka S, Vlach O, Stejskal L, Chaloupka R et al. Conservative treatment versus surgery in spondylotic cervical myelopathy: a prospective randomised study. Eur Spine J. 2000;9(6):538-44.

- ↑ 10.010.1 Cook C, Roman M, Stewart KM, Leithe LG, Isaacs R. Reliability and diagnostic accuracy of clinical special tests for myelopathy in patients seen for cervical dysfunction. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009 Mar;39(3):172-8. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2009.2938.

- ↑ 11.011.1 Koakutsu T,Nakajo J, Morozumi N, Hoshikawa T, Ogawa S, and Ishii Y. Cervical myelopathy due to degenerative spondylolisthesis. Ups J Med Sci. 2011; 116(2): 129–132.

- ↑ 12.012.1 Yonenobu K. Cervical radiculopathy and myelopathy: when and what can surgery contribute to treatment? Eur Spine J. 2000; 9(1): 1-7.

- ↑ 13.013.1 Harrop JS, Naroji S, Maltenfort M, Anderson DG, Albert T, Ratliff JK et al. Cervical myelopathy: a clinical and radiographic evaluation and correlation to cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010 Mar 15;35(6):620-624.

- ↑ Park SJ, Kim SB, Kim MK, Lee SH and Oh IH. Clinical features and surgical results of cervical myelopathy caused by soft disc herniation. Korean J Spine. 2013;10(3):138-143.

- ↑ 15.015.1 Sato T, Horikoshi T, Watanabe A, Uchida M, Ishigame K, Araki T et al. Evaluation of cervical myelopathy using apparent diffusion coefficient measured by diffusion-weighted imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2012; 33(2):388-392.

- ↑ Harrop, James S; Naroji, Swetha; Maltenfort, Mitchell; Anderson, D. Greg; Albert, Todd; Ratliff, John K; Ponnappan, Ravi K; Rihn, Jeffery A; Smith, Harvey E; Hilibrand, Alan; Sharan, Ashwini D; Vaccaro, Alexander. Cervical Myelopathy: A Clinical and Radiographic Evaluation and Correlation to Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy. Spine 10 February 2010 [epub ahead of print]

- ↑ 17.017.1 Chad Cook, Christopher Brown, Robert Isaacs, Matthew Roman, Samuel Davis, and William Richardson. Clustered clinical findings for diagnosis of cervical spine myelopathy. J Man Manip Ther. 2010 December; 18(4): 175–180.

- ↑ 18.018.118.2 Vitzthum H and Dalitz K. Analysis of five specific scores for cervical spondylogenic myelopathy. Eur Spine J. 2007; 16(12): 2096–2103.

- ↑ Tanaka N, Konno S, Takeshita K, Fukui M, Takahashi K, Chiba K et al. An outcome measure for patients with cervical myelopathy: the Japanese Orthopaedic Association Cervical Myelopathy Evaluation Questionnaire (JOACMEQ): an average score of healthy volunteers. J Orthop Sci. 2014 Jan;19(1):33-48.

- ↑ Kadanka Z, Bednarík J, Vohánka S, Vlach O, Stejskal L, Chaloupka R, Filipovicová D, Surelová D, Adamová B, Novotný O, Nemec M, Smrcka V, Urbánek I. Conservative treatment versus surgery in spondylotic cervical myelopathy: a prospective randomised study. Eur Spine J (2000) 9 :538–544

- ↑ 21.021.121.221.321.421.521.621.721.8 Almeida GP, Carneiro KK and Marques AP. Manual therapy and therapeutic exercise in patient with symptomatic cervical spondylotic myelopathy: a case report. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2013 Oct;17(4):504-9.

- ↑ Massimo Leonardi, Norbert Boos , Degenerative disorders of the cervical spine

- ↑ 7 Law MD Jr, Bernhardt M, White AA 3rd.Cervical spondylotic myelopathy: a review of surgical indications and decision making. Yale J Biol Med. 1993 May-Jun;66(3):165-77.

- ↑ Kadaňka, Z., et al. “Conservative treatment versus surgery in spondylotic cervical myelopathy: a prospective randomised study.” European Spine Journal 9.6 (2000): 538-544.

- ↑ Kadaňka, Zdeněk, et al. “Cervical spondylotic myelopathy: conservative versus surgical treatment after 10 years.” European Spine Journal 20.9 (2011): 1533-1538.

- ↑ 26.026.1 Fouyas, Ioannis P., Patrick FX Statham, and Peter AG Sandercock. “Cochrane review on the role of surgery in cervical spondylotic radiculomyelopathy.” Spine 27.7 (2002): 736-747.

- ↑ Shimomura, Takatoshi, et al. “Prognostic factors for deterioration of patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy after nonsurgical treatment.” Spine 32.22 (2007): 2474-2479.

- ↑ Rhee, John M., et al. “Nonoperative management of cervical myelopathy: a systematic review.” Spine 38.22S (2013): S55-S67.

- ↑ Browder DA, Erhard RE and Piva SR. Intermittent cervical traction and thoracic manipulation for management of mild cervical compressive myelopathy attributed to cervical herniated disc: a case series. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004;34(11):701-712.

- ↑ Joghataei, Mohammad Taghi, Amir Massoud Arab, and Hossein Khaksar. “The effect of cervical traction combined with conventional therapy on grip strength on patients with cervical radiculopathy.” Clinical rehabilitation 18.8 (2004): 879-887.

- ↑ Binder, Allan I. “Cervical spondylosis and neck pain.” BMJ: British Medical Journal 334.7592 (2007): 527-531.

- ↑ Kay TM, Gross A, Goldsmith C, Santaguida PL, Hoving J, Brontfort G, et al, Cervical Overview Group. Exercises for mechanical neck disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005

- ↑ Annemie I. F. Spooren, Yvonne J. M. Janssen-Potten, Eric Kerckhofs and Henk A. M. Seelen. Outcome of motor training programmes on arm and hand functioning in patients with cervical spinal cord injury according to different levels of the icf: a systematic review. J Rehabil Med 2009; 41: 497–505

- ↑ Nomura, Takuo, et al. “A subclinical impairment of ventilatory function in cervical spondylotic myelopathy.” Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation 85.7 (2004): 1210-1211.

- ↑ G. Aufdemkampe, J.B. Den Dekker, I. Van Ham, B.C.M. Smits-Engelsman, P. Vaes. Jaarboek fysiotherapie-kinesitherapie 2000. Bohn Stafleu Van Loghum, 275 p

- ↑ Ogawa, Yuto, et al. “Postoperative factors affecting neurological recovery after surgery for cervical spondylotic myelopathy.” Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine 5.6 (2006): 483-487.