Original Editor – Jin Yoo

Top Contributors – Jin Yoo

Introduction [1]

In the acute care setting, intravenous (IV) lines have varied functions:

- to infuse fluids, nutrients, electrolytes, and medication

- to obtain venous blood samples

- to insert catheters into the central circulatory system

Common areas of placement are in the forearm or back of the hand.

There are two types of venous access: peripheral and central.

Peripheral IV (PIV) [2]

Overview:

- Common and preferred method for short-term therapy (

- A short intravenous catheter is inserted by percutaneous venipuncture into a peripheral vein

- Held in place with a sterile transparent dressing to keep site sterile and prevent accidental dislodgement

- Upper extremities are the preferred sites for insertion

- Usually attached to IV extension tubing with a positive pressure cap

Safety Considerations:

- Increased risk of systemic complications in cardiac and renal patients as well as pediatric patients, neonates, and the elderly

Central Venous Catheter (CVC) [2]

Overview:

- Also known as a central line or central venous access device

- Inserted into a large vein in the central circulation system (guided by ultrasound)

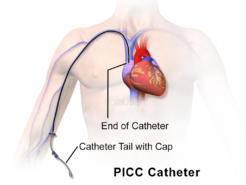

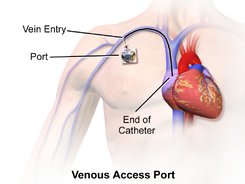

- Tip of catheter terminates in the superior vena cava leading to an area just above the right atrium

- Can remain in place for more than a year

Sub-types:

- Peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC)

- Subcutaneous or tunneled central venous catheter (“Hickman”, “Broviac”, “Groshong”)

- Implanted central venous catheter (ICVC, or port-a-cath)

Commonly seen in patients who:

- require antineoplastic, toxic medications, multiple, vesicant/irritant medications

- are seriously/chronically ill

- require central venous pressure monitoring

- require long-term venous access/dialysis

- require total parenteral nutrition

- have poor vasculature

- have had multiple PIV insertions/attempt

Safety Considerations:

- Heightened risk for developing a nosocomial infection (need strict adherence to aseptic technique)

Complications [2]

| Phlebitis | – inflammation of the vein’s inner lining (tunica intima)

– localized redness, pain, heat, and swelling which can track up the vein leading to a palpable venous cord |

| Infiltration | – non-vesicant (IV solution) is inadvertently administered into surrounding tissue

– pain, swelling, skin around insertion site is cool to touch, change in quality or flow of IV, tightening of skin around IV site, fluid leaking from IV site, and frequent alarms on IV pump |

| Extravasation | – vesicant solution (medication) inadvertently leaks into surrounding tissue causing tissue damage

– similar signs and symptoms as infiltration but with additional burning, stinging, redness, blistering, or necrosis of tissue |

| Hemorrhage | – bleeding from puncture site |

| Local Infection at IV Site | – purulent drainage from site

– usually 2 – 3 days after an IV is started |

| Pulmonary Edema | – also known as “fluid overload” or “circulatory overload”

– caused by excess fluid accumulation in the lungs due to excessive fluid in the circulatory system |

| Air Embolism | – presence of air in the vascular system that travels to the right ventricle and/or pulmonary circulation

– reported more frequently during catheter removal than insertion – sudden SOB, continued coughing, breathlessness, shoulder/neck pain, agitation, feeling of impending doom, light headedness, hypotension, wheezing, increased heart rate, altered mental status, and jugular venous distension |

| Catheter Embolism | – small part of cannula breaks off and flows into vascular system |

| Catheter-related Bloodstream Infection | – microorganisms are introduced into blood through puncture site, hub, or contaminated IV tubing/solution

– can lead to bacteremia or sepsis * perform hand hygiene and strict aseptic technique |

Additional Complications with the CVC

| Catheter-related Thrombosis (CRT) | – long term CVC use may lead to the development of a blood clot

– mostly occurs in the upper extremities – pain, tenderness to palpation, swelling, edema, warmth, erythema, and development of collateral vessels in the surrounding area (most are asymptomatic) – prior catheter infections increase the risk of developing a CRT |

Method of Infusion [2]

Gravity

The infusion rate will be regulated by using a clamp on the IV tubing which can either speed up or slow down the flow of IV fluids.

Electronic Infusion Pump (EID)

The infusion rate is regulated by an electronic pump to deliver the fluids at the correct rate or volume. An IV pump will commonly be used for all CVC devices, opioid infusions (PCA), pediatric patients, and infusion rates below 60 ml/hr.

Physiotherapy Implications [3]

Key points for management :

- Ensure there is adequate tubing to roll, sit up, and ambulate the patient without pulling lines

- Note the dosage/rate of drugs being delivered (especially by infusion pumps)

- Check patency of drip

- Check if there is blood tracking in the tubing

- Check if the IV line has tissued

Key points for pump management

- For patient controlled analgesia (PCA), note if the system is in patient ‘lock-out mode’ (patient will not be able to use delivery button until the mode is cleared)

- Keep note of the alarm silence button

- While all pumps run on battery, ensure that cords are still plugged into the wall supply when patients are non-ambulant

- All pumps can be transferred to mobile intravenous poles (may need nurse assistance of the pumps are locked)

References

- ↑ Dutton M. Introduction to Physical Therapy and Patient Skills. New York: McGraw Hill; 2014.

- ↑ 2.02.12.22.3 Doyle GR, McCutcheon. Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care. Victoria, BC: BC Campus; 2015 Available from: https://opentextbc.ca/clinicalskills/ [Accessed 18th April 2019].

- ↑ Main E, Denehy L. Cardiorespiratory Physiotherapy: Adults and Paediatrics. 5th ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier. 2016.

- ↑ The Ottowa Hospital. 7. Patient Controlled Analgesia. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3P15bzVXObg [last accessed 18/04/2019]