Definition/Description

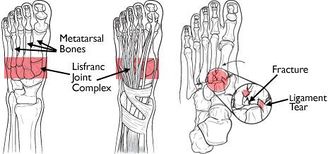

Lisfranc injuries involve the displacement (or dislocation) of the metatarsal bones from the tarsus, particularly as it relates to the second tarsometatarsal (tarsometa-tarsal) joint and the Lisfranc ligament. [1]

The severity of the injury can range from simple to complex and may involve several joints and bones of the mid-foot. It is commonly misdiagnosed as a sprain, particularly if the mechanism of injury is a simple twist and fall,

Clinically relevant anatomy

The foot can be subdivided into three parts : the forefoot area which contains the toes, the midfoot area consisting the small bones called navicular, cuneiform and cuboid. The third part is the hindfoot consisting of the talus (lower ankle) and the calcaneus (heel).

The Lisfranc joints are tarsometaral articulations. In the normal Lisfranc joint complex, first 3 metatarsal bases articulate with their respective cuneiforms, and the lateral 2 metatarsals articulate with the cuboid. The second metatarsal base is tightly recessed in a mortise formed by the 3 cuneiform bones. The intertarsal ligaments, dorsal and plantar tarsalmetatarsal (TMT) ligaments, and transverse ligaments provide soft tissue stability.[2]

The Lisfranc ligament is a large band of plantar collagenous tissue that spans the articulation of the medial cuneiform and the second metatarsal base.[3][4]

While transverse ligaments connect the bases of the lateral four metatarsals, no transverse ligament exists between the first and the second metatarsal bases. The joint capsule and dorsal ligaments form the only minimal support on the dorsal surface of the Lisfranc joint. [4]

The basy architecture of this joint, specifically the ‘keystone’ wedging of the second metatarsal of the cuneiform forms the focal point that supports the entire tarsometatarsal articulation.[4]

For a more detailed and review of the ankle and foot anatomy.

Epidemiology /Etiology

Injuries to the Lisfranc joint are usually the result of combined external rotation and compression force. Injuries can be caused by either direct or indirect trauma. Injuries to the joint are often missed due to anatomical complexity and rarity.[6] They may be caused by a low-energy injury such as a simple twist or fall. They commonly occur when a person stumbles over the top of a plantar flexed foot. Direct trauma such as a fall from a high may also cause a Lisfranc injury. These high-energy injuries can result in multiple dislocations and fractures in the foot. There is a high incidence amongst football players.

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation

Clinically, with the calcaneus held stable, abduction or pronation of the forefoot will produce pain over the midfoot. Typically, there is difficulty weight bearing, minimal swelling over the midfoot, and palpable tenderness along the tarsometatarsal joints.[7] Athletes may have pain with running on the toes and with push-off phase of running.[8]

Lisfranc injuries can include sprains, dislocations, fractures of all three at the same time. An injury can be caused by an indirect or direct trauma. A direct trauma is can be caused when an external force works on the foot, for example when you drop something heavy on it. An indirect trauma is caused when a twisting of the foot happens after it gets caught on something. An injury at the Lisfranc joint is mostly the result of the combined external rotation and compression force.[6]

Like in most cases of injury, an injury to the Lisfranc joint can have some complications. The most common complication is post-traumatic arthritis of the joint. Post-traumatic arthritis mimics degenerative arthritis, but it’s course is accelerated because of severe injury. This can cause chronic pain in the injured joint. [9]

Another complication is called the compartment syndrome. It occurs when traumatic injury causes swelling and bleeding to raise the pressure within the tissues of the body.[10] The incidence of the Lisfranc joint fracture dislocations is one case per 55,000 persons each year. As many as 20 percent of the Lisfranc joint injuries are missed on initial anteroposterior and oblique radiographs.[4]

Differential diagnosis

The injury was first noticed in the early 1800s by the French surgeon Jacques Lisfranc. The injury was caused when soldiers were thrown of their horses and their foot was stuck into the stirrup. Now automobile accidents, falls and sport injuries can also lead to an injury on the Lisfranc joint. This kind of injury is more and more seen by football players, gymnasts and ballet dancers. The injury can be potentially career ending.[11]

The Lisfranc joint injury isn’t easy to be diagnosed, apart from when there is a marked swelling and radiographic changes noticeable. The most common symptoms are [12]:

- Swelling of the foot and/or ankle

- Bruising of the foot and/or ankle

- Pain usually in the middle part of the foot

- Widening of the midfoot area

- Large bump on the top midfoot area

- Not being able to put any weight on the injured foot

Differential diagnosis to Lisfranc injury includes: midfoot sprain, metatarsal fracture, cuboid fracture, posterior tibialis tendon dysfunction, and compression injuries to the navicular.[7]

Diagnostic procedures

Currently, there are no specific clinical tests to confirm the extent of an injury. Therefore, diagnosis of ligmentous injuries may be based on a high level of suspicion. In suspected Lisfranc injuries, use of imaging modalities is warrented. Recommended radiographs include anteroposterior, lateral, and 30 degree internal oblique projections in weight-bearing.[2]

The injury can be seen on x-ray. Sometimes there is a x-ray needed of the uninjured foot to see if there is an injury or not. A weight-bearing radiograph is necessary, because a non weight-bearing x-ray may not reveal any injury[3].

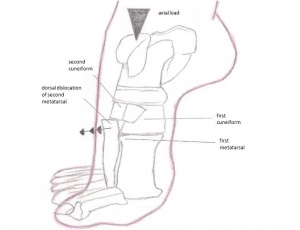

On x-ray, dislocation of the tarsometatarsal joint is indicated by :

- Loss of in-line arrangement of the lateral margin of the first metatarsal base with the lateral edge of the medial cuneiform.

- Loss of in-line arrangement of the medial margin of the second metatarsal base with the medial edge of the middle cuneiform in the weight-bearing anteroposterior view.

- The presence of small avulsed fragments, which are further indications of ligamentous injury and probable joint disruption.[13]

The Lisfranc injury can also be physical examined. When Lisfranc joint complex injury is suspected, palpation of the foot should begin distally and continue proximally to each tarsometatarsal articulation. Tenderness along the metatarsal joints supports the diagnosis of midfoot sprain with potential for segmental instability.

Pain can localize to the medial or lateral aspect of the foot at the tarsometatarsal region on direct palpation, or it can be produced by abduction and pronation of the forefoot while the hindfoot is held fixed.[3]

The dorsalis pedis pulse and capillary refill should also be evaluated. It can be disrupted in a severe dislocation.

Computed tomography should be reserved for questionable cases such as the severely injured foot where adequate positioning cannot be obtained or cases where the multiplicity of fractures and dislocations makes complete evaluation difficult. Computed tomography should also be used when adequate reduction cannot be achieved to determine the presence of bony fragments or entrapped soft tissues that may be hindering reduction.[14][15]

Medical management

Medical management to Lisfranc injuries may be operative or non-operative depending on severity. In mild to moderate sprains, the lower extremity may be immobilized for approximately six weeks. More severe injuries may be treated with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF). Following ORIF, the foot is usually immobilized for 8-12 weeks.[8]

If the injury is severe and its believed that the damage is beyond repair, a fusion may be recommended as the initial surgical procedure. A fusion is a “welding” process in which the idea is to fuse together the damaged bones so that they heal into a single, solid piece.

Physiotherapy management

If a mild sprain is the case and the radiograph shows no diastosis, immobilization is suggested. If there is a minimal displacement of the bones, a stiff walking cast applied for approximately eight weeks is an appropriate alternative. However, the most common treatment is to secure the fractured and dislocated bones with either internal (screws) or external (pins) fixation.[10]

Physiotherapy intervention begins shortly following immobilisation in both surgical and conservative treatment. Interventions include: oedema reduction, strengthening to address post immobilisation atrophy, flexibility exercises, gait training, and manufacturing of foot orthoses to help support the tarsometatarsal articulations. [7]

Other therapeutic exercises are doing stairs, swimming, walking in the pool, standing on toes, jump rope, squats.[13]

Here are some other exercises for a Lisfranc injury: [16]

- Range of motion exercises: Plantarflexion, dorsiflexion, inversion, eversion and writing the alphabet with your toes.

- Toe and midfoot arch flexibility stretch: Let your heel rest on the ground and put up your toes up against a wall. Now gently try to press your toes into the wall so you can feel the stretching of your foot sole.

- Midfoot arch massage.

- Calf stretches to regain the flexibility in the calves.

- Ankle and foot strengthening exercises: These exercises are the same exercises as the range of motion exercises, but with a resistance band. You can also do towel scrunches (lay down a towel and scrunch the towel with your toes).

- Balance exercises: On 1 leg, with your eyes closed, standing on a foam pillow, standing on a wobble board.

- Plyometrics and jumping exercises: Jumping and landing, single leg hop, drop jump.

According to Reinhardt KR et al. primary partial arthrodesis is a beneficial therapy for a Lisfranc injury. To prove this, there has been a study with 25 patients (12 with a ligamentous Lisfranc injury and 13 with a combined Lisfranc injury) with a median age of 46 years and an average follow-up of 42 months. The score of the American Orthopedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) was 81/100. Most of the patients lost some points for mild pain, limitations of recreational activities, and fashionable footwear requirements. In the last follow-up, the patients regained an average of 85% of their pre-injury physical activity and 21 patients expressed satisfaction of the therapy. Conclusion: Primary partial arthrodesis produces well clinical and patient based outcomes.[17]

Another study tells us that primary arthrodesis does not have any benefits regarding severe fracture-dislocations. Open reduction and temporary screws or K-wire fixation is in this case the treatment of choice.[18]

A systematic review compared primary partial arthrodesis to ORIF and this study shows that the AOFAS-score of ORIF patients was 72.5/100. The AOFAS-score of patients with primary partial arthrodesis was 88% within one year of follow-up. This study compared six articles to 193 patients. Conclusion: Both therapies have equivalent results but the primary partial arthrodesis has a small advantage in terms of clinical outcomes.[19]

After the primary partial arthrodesis patients need a plaster cast. Afterwards, they can start the revalidation process. First of all, they’ll need a walker. They use the walker when they try to stand up or while they are walking. The patients can do exercises without the walker, but then they have to sit down. After 4 weeks, patients start wearing the walker less and less. When this is successful, patients can start doing exercises while standing up. They start with low intensity exercises (plantar flexion and dorsal flexion of the foot and toe stand (2x/day, 3x 10-15 repetitions). Then they start with more difficult exercises (cycling, rowing, stepping). Watch out, never cross the pain threshold during the exercises.

References

- ↑ Wynter S, Grigg C. ↑ 2.02.1 Wadsworth DJ, Eadie NT. Conservative Management of Subtle Lisfranc Joint Injury: A Case Report. JOSPT 2005:35(3):154-164.

- ↑ 3.03.13.2 Trevino SG, Kodros S. ↑ 4.04.14.24.3 Englanoff G, Anglin D, Hutson HR. ↑ Lisfranc Injuries – Everything You Need To Know – Dr. Nabil Ebraheim. Avalaible from:↑ 6.06.1 Nunley JA, Vertullo CJ. ↑ 7.07.17.2 Reischl SF, Noceti-DeWit LM. Current concepts of orthopaedic physical therapy. 2nd edition. Alexandria: Orthopaedic Section, APTA, 2006

- ↑ 8.08.1 Burroughs KE, Reimer CD. Fields KB. ↑ Teo YH, Verhoeven W. ↑ 10.010.1 Orthopedics About. Lisfranc injuries. What is a Lisfranc injury? Available from: ↑ Medscape. Lisfranc fracture dislocation. Available from: ↑ Very Well. Lisfranc Injury. ↑ 13.013.1 Myerson M. ↑ Pearse EO, Klass B, Bendall SP. The ‘ABC’ of examining foot radiographs. The Royal College of Surgeons of England 2005;87:449–451.

- ↑ Brow D, Gumbs RV. Lisfranc fracture dislocations: report of two cases. Journal of the national medical association 1991;83(4):366-369.

- ↑ Brett Sears, PT. Exercise Program after a Lisfranc Fracture and Dislocation (Starting an Exercise Program After a Lisfranc Fracture) October 29, 2017

- ↑ Reinhardt KR, Oh LS, Schottel P, Roberts MM, Levine D. ↑ Mulier T, Reynders P, Sioen W, Van Den Bergh J, De Reymaeker G, Reynaert P, Broos P. ↑ Sheibani-Rad S, Coetzee JC, Giveans MR, DiGiovanni C. function gtElInit() { var lib = new google.translate.TranslateService(); lib.setCheckVisibility(false); lib.translatePage('en', 'pt', function (progress, done, error) { if (progress == 100 || done || error) { document.getElementById("gt-dt-spinner").style.display = "none"; } }); }

Ola!

Como podemos ajudar?