Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is the fifth most common reason for physician visits, which affects nearly 60-80% of people throughout their lifetime. The lifetime prevalence of low back pain is reported to be as high as 84%, and the prevalence of chronic low back pain is about 23%, with 11-12% of the population being disabled by low back pain[1].

There are different definitions of low back pain depending on the source. According to the European Guidelines for prevention of low back pain, low back pain is defined as “pain and discomfort, localized below the costal margin and above the inferior gluteal folds, with or without leg pain”[2] Another definition, according to S.Kinkade, which resembles the European guidelines is that low back pain is “pain that occurs posteriorly in the region between the lower rib margin and the proximal thighs”.[3] The most common form of low back pain is the one that is called “non-specific low back pain” and is defined as “low back pain not attributed to recognizable, known specific pathology”[2].

Low back pain is usually categorized in 3 subtypes: acute, sub-acute and chronic low back pain. This subdivision is based on the duration of the back pain. Acute low back pain is an episode of low back pain for less than 6 weeks, sub-acute low back pain between 6 and 12 weeks and chronic low back pain for 12 weeks or more.[2]

Low back pain that has been present for longer than three months is considered chronic. More than 80% of all health care costs can be attributed to chronic LBP. Nearly a third of people seeking treatment for low back pain will have persistent moderate pain for one year after an acute episode[4][5][6]. It is estimated that seven million adults in the United States have activity limitations as a result of chronic low back pain[7].

A fairly recent study looked at low back pain and the treatment with a long course of antibiotics in a certain population. The inclusion criteria was a previous disc herniation, >6 months back pain and type 1 modic changes adjacent to the previous herniation on MRI scan. Modic changes are where oedema is present in the vertebral body. These patients were treated with 100 days of antibiotics and at reassessment and 1 year follow up there was a statistical significant improvement in their pain levels. Therefore this is potentially something to consider in this population. [8][9]However, recent clinical guidelines issued by the NICE in the UK[10], The Danish Health Authority[11] and American College of Physicians[12] do not mention the use of antibiotics in the treatment of low back pain. Another guideline issued by the KCE in Belgium in 2017[13] states that it does not recommend the use of antibiotics, at any stage, for the treatment of low back or radicular pain.

Low Back Pain Examination[14]

The first aim of the physiotherapy examination for a patient presenting with back pain is to classify the patient according to the diagnostic triage recommended in international back pain guidelines[15]. Serious (such as fracture, cancer, infection and ankylosing spondylitis) and specific causes of back pain with neurological deficits (such as radiculopathy, caudal equina syndrome)are rare[16] but it is important to screen for these conditions[15][17]. Serious conditions account for 1-2% of people presenting with low back pain and 5-10% present with specifics causes LBP with neurological deficits[18]. When serious and specific causes of low back pain have been ruled out individuals are said to have non-specific (or simple or mechanical) back pain.

Non-specific low back pain accounts for over 90% of patients presenting to primary care[19] and these are the majority of the individuals with low back pain that present to physiotherapy. Physiotherapy assessment aims to identify impairments that may have contributed to the onset of the pain, or increase the likelihood of developing persistent pain. These include biological factors (eg. weakness, stiffness), psychological factors (eg. depression, fear of movement and catastrophisation) and social factors (eg. work environment)[14]. The assessment does not focus on identifying anatomical structures (eg. the intervertebral disc) as the source of pain, as might be the case in peripheral joints such as the knee[14]. Previous research and international guidelines suggest it is not possible or necessary to identify the specific tissue source of pain for the effective management of mechanical back pain[15][17][20]. Therefore the use of diagnostic imaging, especially in the first month, is not recommended. Diagnostic management should only be used if low back pain does not respond to recommended protocols and the management of the condition needs to be changed or more serious pathology is suspected.[21]

Leg pain is a frequent accompaniment to low back pain, arising from disorders of neural or musculoskeletal structures of the lumbar spine. Differentiating between different sources of radiating leg pain is important to make an appropriate diagnosis and identify the underlying pathology. Schäfer et al[22] proposed that low back-related leg pain be divided into four subgroups according to the predominating pathomechanisms involved. Each group presents with a distinct pattern of symptoms and signs although there may be considerable overlap between the classifications. The importance of distinguishing low back-related leg pain into these four groups is to facilitate diagnosis and provide a more effective, appropriate treatment:

- Central sensitization with mainly positive symptoms such as hyperalgesia

- Denervation with significant axonal damage showing predominantly negative sensory symptoms and possibly motor loss

- Peripheral nerve sensitization with enhanced nerve trunk mechanosensitization

- Somatic referred pain from musculoskeletal structures, such as the intervertebral disc or facet joints.

Management strategies

There has been a recent move away from a pathoanatomical approach to managing individuals with back pain. No longer do we aim to diagnose a structure at fault and aim our treatment at that particular structure. Research and international guidelines suggest it is not possible or necessary to identify the specific tissue source of pain for the effective management of mechanical back pain[15][17][23]. Instead a stratified approach to managing low back pain has become popular.

Recent guidelines[10][11][12][13]recommend advice and non-pharmacological management such as physiotherapy interventions that include exercise and manual therapy. Acupuncture is now only recommended by the ACP[12] for the management of individuals with back pain. To direct these treatment plans stratified care has been suggested as an appropriate approach[24]. Stratified care is the targeting of treatment to subgroups of patients based on characteristics. Foster et al[24] suggest that there are 3 different approaches to stratification that have good evidence:

In a clinical trial study conducted by Finta et al [25][26].

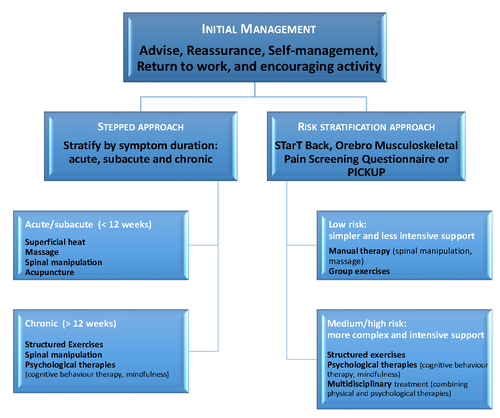

Recently Almeida et al suggest two approaches, based on recent clinical guidelines, when considering the management of patients with non-specific low back pain[30].

- The traditional approach – stratifying patients by symptom duration – acute (less than 6 weeks), sub-acute (6-12 weeks) and chronic (more than 12 weeks) and then using a stepped approach to treatment beginning with simple therapies and only progressing to more complex treatments if there is no significant improvement. This approach is recommended by the US[12] and Danish[11] guidelines.

- The use of Risk prediction tools, such as STarT Back, [10]

and Belgian[13] guidelines, to determine the best treatment protocol based on their risk of poor clinical outcome.

The use of these different stratification approaches vary around the world and there are overlaps between these three different approaches. A perfect subgrouping approach would include all three of these approaches. These models don’t replace clinical reasoning or experience but they do warrant judicious exploration in clinical practice in appropriate settings.

Contraindications

There are few contraindications to physiotherapy interventions for mechanical back pain as long as the diagnostic triage has been applied to identify people with serious causes of back pain. Osteoporosis is a contraindication to most manual therapy. Importantly, physiotherapists work in a model where effects of treatments are closely reassessed to minimise the likelihood of increasing symptoms or adverse events[14].

Prevention of Low Back Pain

Prevention is also categorized according to three types:

- Primary prevention is defined as “specific practices for the prevention of disease or mental disorders in susceptible individuals or populations. These include health promotion, including mental health; protective procedures, such as communicable disease control; and monitoring and regulation of environmental pollutants. Primary prevention is to be distinguished from secondary prevention and tertiary prevention.”[31]

- Secondary prevention is defined as “the prevention of recurrences or exacerbations of a disease that already has been diagnosed. This also includes prevention of complications or after-effects of a drug or surgical procedure”[31]

- Tertiary prevention as “measures aimed at providing appropriate supportive and rehabilitative services to minimize morbidity and maximize quality of life after a long-term disease or injury is present”.[31]

The guidelines discuss different possibilities to prevent low back pain. Physical exercise is recommended to prevent consequences of low back pain, such as an absence of work and occurrence of further episodes. Physical exercise is especially useful in training back extensors and trunk flexors in conjunction with regular aerobic training. There is no specific recommendation of exercise frequency or intensity.[2][3][32] With regard to the back school programs, a high intensity program is advised in patients with recurrent and lasting low back pain but not in preventing low back pain. The program consists of exercises and an educational skills program. Education and information alone or based on the biomechanical model has only a small effect. Education and information in combination with other interventions, in a treatment setting based on the biopsychosocial model has a better effect. Information based on the biopsychosocial model is focused on beliefs in low back pain and reducing work loss caused by low back pain. This attitude of giving information has a positive effect on back pain beliefs.[2] It is important to know that individually tailored programs and intervention may have more results in comparison to group interventions.[32] Lumbar supports, back belts and shoe insoles are not recommended in the prevention of low back pain. Lumbar supports and back belts have also been shown to have a negative effect on back pain beliefs and are therefore are not recommended in preventing low back pain.[2][3] Specific mattresses and chairs for prevention have no evidence in favor or against. Medium support mattresses may decrease existing persistent symptoms of low back pain.[2] Ergonomic adjustments regarding work environment can be necessary and useful to achieve earlier return to work.[2][33]

Guidelines

Related Pages

Failed to load RSS feed from http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=129mA77YOoV: There was a problem during the HTTP request: 422 Unprocessable Entity

34.↑ Finta R, Nagy E, Bender T. The effect of diaphragm training on lumbar stabilizer muscles: a new concept for improving segmental stability in the case of low back pain. Journal of pain research. 2018;11:3031.

Como podemos ajudar? Presentations

Recent Related Research (from

References

Ola!