Original Editors Ashley Bohanan, Alisha Lopez, Hannah Duncan, Neha Palsule, Brittany Buenteo

Lead Editors

Search Strategy

Databases Searched: Definition/Description

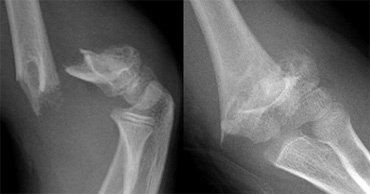

Pediatric humeral fractures can occur in several locations including the proximal humerus, shaft (diaphysis), or the distal humerus (supracondylar ridges, medial and lateral epicondyles). Of these, supracondylar fractures are the most common[1] followed by lateral humeral condylar fractures.[2] These fractures can result from a direct hit or a fall onto an outstretched hand (FOOSH).[1] In addition, these injuries occur predominantly in the younger population because their bodies are still in development.[1] (Photos Courtesy of The Radiology Assistant)

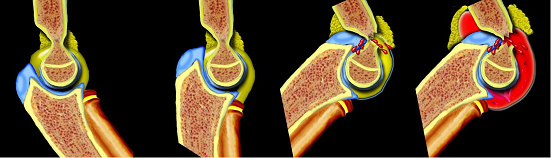

Upper extremity fractures are more common than lower extremity fractures in children.[1] Proximal humeral fractures should be the first diagnosis considered in children between 9 and 15 years of age that sustained a shoulder injury.[1] Additionly, this fracture can occur in newborns due to a birth-related injury.[1] Humeral shaft fractures are uncommon in children. If this injury occurs without a major trauma, it should increase the suspicion for a possible non-accidental trauma (child abuse).[1] Lateral humeral condylar fractures account for 12-20% of all pediatric elbow fractures and occurs mostly in children about 6 years of age.[2] Medial epicondyle fractures make up 11-20% of all injuries of the elbow in children with 30-55% of cases associated with a dislocation of the elbow.[3] Supracondylar fractures comprise 65-75% of all elbow fractures in children.[4] These injuries are the most challenging and have the highest complication rate.[1] Supracondylar fractures mostly occur between the ages of 5 and 10[5] with the peak incidence occurring between 5-8 years of age (after this, dislocations become more frequent).[4] This injury occurs during this time period due to greater likelihood of falls, general ligamentous laxity, weak bone structure at the supracondylar region,[1] and a joint position of hyperextension.[6] Supracondylar fractures are more common in males and on the non-dominant side.[4] Mechanism of injury:

Proximal humeral fractures

Lateral humeral condyle fractures

Supracondylar fractures

Hyperextension Injury

Extreme Valgus (Photos Courtesy of The Radiology Assistant) Appropriate age and mechanism of injury are highly suggestive factors when diagnosing a pediatric humeral fracture. Upon presentation, physicians should screen for neurovascular compromise and always be mindful of non-accidental injuries.

Supracondylar fractures Lateral Condyle Fractures (Photos Courtesy of The Radiology Assistant)

Currently, there is no standard scale or functional measure used to assess the effectiveness of treatment in pediatric patients with a humeral fracture. Numeric pain rating scale (NPRS), girth measurements, and range of motion (ROM) measurements should be included in the examination and can be used as outcome measures. The Mayo Elbow Performance Scale (MEPS) is a commonly used physician-based elbow rating scale that has been utilized in studies investigating pediatric humeral fractures.[8]

History:

It is essential to obtain a thorough explanation for the fracture in order to distinguish accidental from non-accidental injuries (pathological fractures, child abuse).The following questions should be addressed:[9][4] Common signs of child abuse:

Observation:

Palpation:

Neurological Exam: Assessment of joints above and below injury:

Special tests:

Circulatory/Vascular:

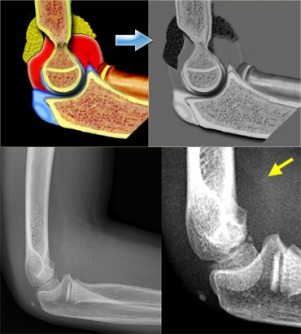

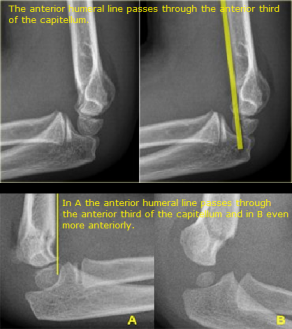

Examination procedures should be performed with caution as the child will experience intense pain and fear during the exam. Reassurance and comfort to the patient and their parent/guardian is important.[1] Radiography Interpreting radiographs of pediatric humeral fractures is often challenging due to changing epiphyses during childhood[4] and a child’s cooperation. Standard imaging includes: anteroposterior view with the elbow extended, lateral view with the elbow flexed to 90° and forearm in neutral, oblique views, and images of joints above and below.[6] Normal Findings: Anteroposterior View Lateral View Abnormal Findings:

Anterior Humeral Line Fat pad displacement

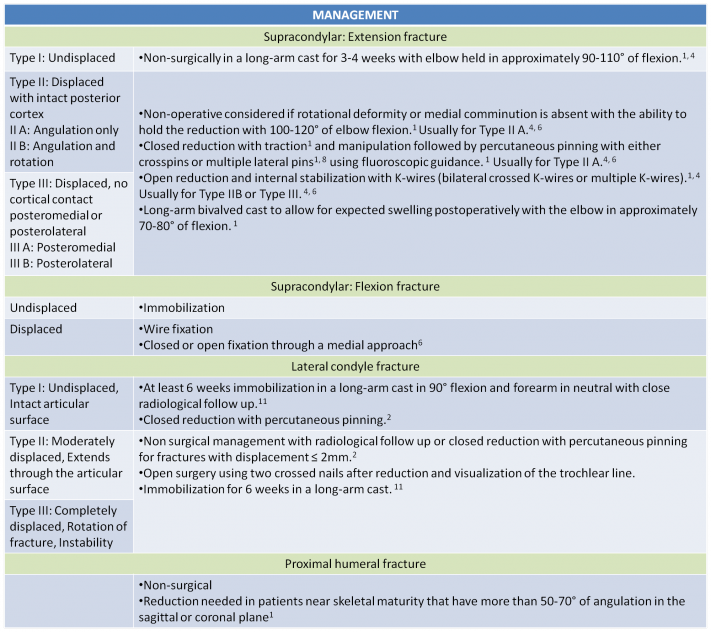

(Photos Courtesy of The Radiology Assistant) Management Gartland’s 1959 classification[1][7][6] and its subsequent modification by Wilkins[6] are the most widely used classification systems. These classifications guide the standard of care for treatment for supracondylar fractures.[1][8][10] Additional factors such as radiographic displacement, mechanism of injury, and soft tissue status are considered to determine the most appropriate treatment.[10] Complications

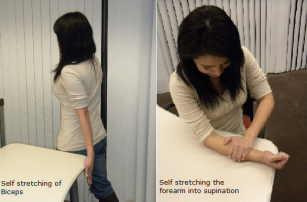

Lateral humeral condyle fracture Supracondylar fracture The indications for physical therapy after supracondylar humeral fractures in children are not clear in the literature, even in the presence of an active or passive limitation of elbow joint motion.[12] Much of the controversy is partly due to an initial recovery in elbow motion with progressive improvements for up to a year regardless of physical therapy.[12][13] Physical therapy is not unsuccessful or totally contraindicated. Children who received physical therapy achieved a more rapid return of normal or near normal elbow range of motion.[12] The primary goals of treatment should focus on pain reduction, healing, rapid recovery of mobility, and avoidance of late complications.[9] At two weeks post proximal humeral fracture gentle pendulum and passive ROM exercises should be implemented.[1] For supracondylar and humeral shaft fractures after the cast is removed, passive and active motion, soft tissue stretching techniques, and strengthening exercises should be implemented to maximize functional outcome.[1][12][4] Moreover, patient education should focus on instructing parents on how to monitor the child’s neurovascular status, recognize signs of compartment syndrome, and skin care around the cast.[1] Recovery is slower in children who are older, immobilized longer, and have a more severe injury.[13] Supracondylar humeral fractures are common in the pediatric population. The child’s age, ossification periods, and mechanism of injury are important to consider. Examining the patient’s neurovascular status is imperative and should be monitored throughout the course of treatment. Stiffness and limited range of motion are common impairments that should be addressed in physical therapy. There is limited evidence for physical therapy treatment and therefore clinicians should implement an impairment based approach.

Failed to load RSS feed from http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=1BE6Yf6ex8rdDS0mLxL9WuK: There was a problem during the HTTP request: 422 Unprocessable Entity

Epidemiology/Etiology

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation

Differential Diagnosis

Outcome Measures

Examination

Medical Management

Physical Therapy Management

Key Research

Resources

Recent Related Research (from

References

see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ 1.001.011.021.031.041.051.061.071.081.091.101.111.121.131.141.151.161.171.181.191.201.211.221.231.241.251.261.27 Hart ES, Grottkau BE, Rebello GN, Albright MB. Broken Bones: Common Pediatric Upper Extremity Fractures – Part II. Orthopaedic Nursing. 2006;25(5):311-323.

- ↑ 2.02.12.22.3 Tejwani N, Phillips D, Goldstein RY. Management of Lateral Humeral Condylar Fracture in Children. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2011;19:350-358.

- ↑ Louahem DM, Bourelle S, Buscayret F, Mazeau P, Kelly P, Dimeglio A, Cottalorda J. Displaced medial epicondyle fractures of the humerus: surgical treatment and results. A report of 139 cases. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery. 2010;130:649-655.

- ↑ 4.004.014.024.034.044.054.064.074.084.094.104.114.124.134.144.154.164.17 Lord B, Sarraf KM. Paediatric supracondylar fractures of the humerus: acute assessment and management. British Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2011;72(1):M8-M11.

- ↑ 5.05.15.25.35.45.55.65.75.8 Ryan LM. Evaluation and management of supracondylar fractures in children. UpToDate. 2010:1-37.

- ↑ 6.06.16.26.36.46.56.66.7 Marquis CP, Cheung G, Dwyer JSM, Emery DFG. Supracondylar fractures of the humerus. Current Orthopaedics. 2008;22(1):62-69.

- ↑ 7.07.17.2 Wu J, Perron A, Miller M, Powell S, Brady W. Orthopedic pitfalls in the ED: pediatric supracondylar humerus fractures. American Journal Of Emergency Medicine. October 2002;20(6):544-550. Available from: CINAHL Plus with Full Text, Ipswich, MA. Accessed November 27, 2011.

- ↑ 8.08.1 Fu D, Xiao B, Yang S, et al. Open reduction and bioabsorbable pin fixation for late presenting irreducible supracondylar humeral fracture in children. International Orthop (SICOT). 2011;35:725-730.

- ↑ 9.09.19.2 Kraus R, Wessel L. The Treatment of Upper Limb Fractures in Children and Adolescents. Dtsch Arztebl. 2010; 107(51-52): 903-910.

- ↑ 10.010.1 Mallo G, Stanat S, Gaffney J. Use of the Gartland classification system for treatment of pediatric supracondylar humerus fractures. Orthopedics. 2010;33(1):19. Available from: CINAHL Plus with Full Text, Ipswich, MA. Accessed November 27, 2011.

- ↑ Marcheix PS, Vacquerie V, Longis B, Peyrou P, Fourcade L, Moulies D. Distal humerus lateral condyle fracture in children: When is the conservative treatment a valid option? Orthopaedics and Traumatology: Surgery and Research. 2011;97:304-307.

- ↑ 12.012.112.212.3 Keppler P, Salem K, Schwarting B, et al. The Effectiveness of Physiotherapy After Operative Treatment of Supracondylar Humeral Fractures in Children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25(3):314-316.

- ↑ 13.013.1 Bernthal NM, Hoshino CM, Dichter D, et al. Recovery of Elbow Motion Following Pediatric Lateral Condylar Fractures of the Humerus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93: 871-877.