Contents

- 1 Definition/Description1,2

- 2 Prevalence2

- 3 Characteristics/Clinical Presentation1,2

- 4 Associated Co-morbidities1,2,3,4

- 5 Medications1

- 6 Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values1

- 7 Etiology/Causes1,5

- 8 Systemic Involvement13

- 9 Medical Management (current best evidence)6

- 10 Physical Therapy Management (current best evidence)6,7,8,9,10,11,12

- 11 Differential Diagnosis18

- 12 Case Reports/ Case Studies

- 13 Resources

- 14 Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)

- 15 References

Definition/Description1,2

Polymyositis (PM) is a chronic inflammatory myopathy, which is classified as a persistent inflammatory muscle disease. PM affects striated muscle fibers, but spares smooth muscle throughout the body and can come on gradually over weeks or months. PM targets proximal musculature, with little to no pain, impairing strength and is characterized by an elevation of serum muscle enzymes and a wide variety of skin abnormalities, sometimes including cardiopulmonary impairments. Although no pain is present, some tenderness may occur directly over involved musculature, but all deep tendon reflexes are preserved. The general approach to treating polymyositis is through pharmacological and conservative treatment to increase strength and prevent development of extra-muscular disease in order to better outcomes for the patient.

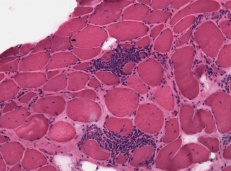

PM is an autoimmune disorder where inflammatory cells (T cells and Macrophages) surround, enter, and destroy fibers. Muscle tissue loss is replaced by fatty tissues in patients with chronic disease. The muscle biopsy image below illustrates the proliferation of inflammatory cells around otherwise normal myofibers.14

Prevalence2

Current literature is unclear about the age of presentation – some articles state it mostly affects adults in their 30’s to 50’s, while other sources say the onset is in adults aged 50-70. Although research shows that it is rare to have an onset earlier than 18 years of age, it has been proven that females are more susceptible to PM than males with a ratio of 2:1. One in 100,000 people have PM with African-Americans more commonly diagnosed than caucasians.

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation1,2

Symptoms are symmetrical and can gradually appear or may fluctuate within short or long periods of time. Functionally, patients may have issues with grabbing a glass off of a high shelf, climbing stairs, or getting up or sitting down on a couch.

With progression of the disease, neck and shoulder girdle musculature can be involved resulting in minimal muscle contraction or paralysis.

Here is a summary of the signs and symptoms

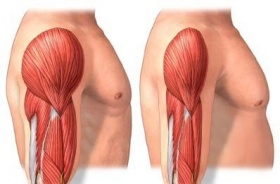

Proximal Muscle Atrophy15

- Proximal muscle weakness

- Difficult swallowing (dysphagia)

- Difficulty speaking

- Mild joint or muscle tenderness

- Fatigue

- Arthralagia

- Shortness of breathe

- Malnutrition

- Weight loss

- Calcium deposits

- Morning stiffness

As PM progresses, it can affect the upper esophagus as well as striated muscle fibers in the chest wall. As a result, patients can have more complex signs and symptoms such as:

- Aspiration pneumonia

- Respiratory failure

- Variety of cardiovascular complications (i.e. CHF, arrhythmias)

- Interstitial lung disease

Associated Co-morbidities1,2,3,4

Since Polymyositis is a autoimmune disease, it is often associated with other autoimmune dieases and infectious disorders:

- Connective tissue diseases: lupus, RA, scleroderma, Sjogrens

- Cardiovascular disease: myocarditis, CHF, heart arrhythmias

- Lung disease

- HIV/AIDS

- Raynauds Phenomenon

Medications1

Earlier treatment is always better – your doctor will decide based on your symptoms what treatment will be more tailored to you. There have not been very many scientific studies which effects insurance coverage and you should be closely monitored for adverse side effects:

- Corticosteroids

- Immunosupressive therapies (If cortico-steroids aren’t working)

1. Corticosteroid sparing agents (Azasan, Imuran, Trexall, Methotrexate, Rheumatrex).

2. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG).

3. Tacrolimus (Prograf)

4. Cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan)

5. Cyclosporine (Gengraf, Neoral, Sandimmune) - Biological therapies (Severe Cases, only if the above two didn’t work)

1. Rituximab (Rituxan)

2. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors (Enbrel, Remicade)

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values1

There are several different diagnostic tools to determine if a patient has polymyositis, it can be a long process and both health care providers as well as patients are encouraged to remain patient:

- Magnetic Resonance imaging (MRI)

- Electromyography

- Muscle Biopsy (looking for inflammation, damage, or infection/abdnormal proteins and enzyme deficiencies)

- Blood Tests:

1. Increased Creatine Kinase

2. Increased Aldolase

Etiology/Causes1,5

The cause is officially unknown, but it has been shown to be related to other autoimmune diseases with detectable level of autoantibodies in their blood, genetics, and some undisclosed viruses. (1)

Systemic Involvement13

Musculoskeletal

Cardiopulmonary

- Dyspnea

- Cough

- Cardiac arrhythmias can occur but are often asymptomatic

Gastrointestinal

- More common manifestation in children

- Hematemesis (vomiting of blood)

- Melena (black, tarry feces)

- Ischemic bowel perforation

Medical Management (current best evidence)6

There is no cure for polymyositis however evidence supports that medical management can relieve patient symptoms and give patients more control over their condition. Management of symptoms can allow patients greater function and a better quality of life.

Symptoms vary greatly from patient-to-patient, and all medications have different side effects. Given the difference in presentation of symptoms and individual reactions to medications the course of medical management is unique to each patient. Management may include a combination of pharmacological intervention, physical therapy, and alternative/holistic medicine. Pharmacological management commonly consists of a combination of corticosteroids and immunosuppressants. Corticosteroids are used to reduce inflammation, relieve pain, and improve strength, while immunosuppressants help to dampen the body’s adverse immune response to the patients muscles.

Pharmacological Management

Corticosteroids

• Prednisone – Typical drug of choice. Used to reduce inflammation, relieve pain, and improve strength. Prednisone is typically prescribed in high doses initially before being tapered to reduce the risk of adverse drug reactions to long-term use of corticosteroids.

Immunosuppressants

• Methotrexate/Azathiprine – often used in combination with prednisone or to allow patients to taper off of Prednisone more quickly. Patients are commonly treated with a combination or Prednisone and Methotrexate from the beginning of their care.

• Cyclophosphamide – more potent than methotrexate and commonly used in patients with disease related lung complications such as interstitial lung disease

Acthar – naturally occurring hormone that is produced in the pituitary gland. Stimulates the release of cortisol from the patient’s adrenal glands, which is a natural alternative to taking corticosteroids. Acthar also reduced the body’s hyperactive immune reponse, thus acting as both a corticosteroid and immunosuppressant. While Acthar would appear to be the ideal pharmacological treatment, there is limited clinical research on its effectiveness. Ongoing studies continue to assess the role of Acthar in the treatment of polymyositis.

Intravenous Immune Globulin (IVIG) – blood product derived from human plasma that actually boosts the body’s immune system response. With immunosuppression being the primary course of medical management it is unclear why some myositis patients benefit from IVIG. IVIG is typically only used in patients who are resistant to other pharmacological treatment.

Biologic Agents – Proteins or monoclonal antibodies that inhibit cytokines, which are key players in myositis inflammation.

Anti-TNF Agents – suppress tumor necrosis factor proteins that are associated with inflammation

Rituximab – Targets B cells (lymphocytes) of the immune system, which play a role in the inflammation associated with polymyositis.

Alemtuzumab – Targets T cells (lymphocytes) of the immune system, which play a role in the inflammation associated with polymyositis

Physical Therapy

Focus on the development of an exercise program to increase physical activity, decrease impairments and disability, and increase overall quality of life.

As with pharmacological management, every patient is different and should consult with their physical therapist to have a specific plan of care outlined that meets their specific needs and goals.

Alternative/Hollistic Medicine

Most physicians recommend a holistic approach to general wellness in addition to pharmacological management. This includes diet/nutrition, appropriate exercise, physical therapy, vitamins, and supplements.

Physical Therapy Management (current best evidence)6,7,8,9,10,11,12

Polymyositis and other idiopathic inflammatory myopathies present with wide ranging systemic clinical manifestations. Among those most relevant to physical therapy are muscle weakness, fatigue, and shortness of breath. Musculature proximal to the trunk is the most affected, with marked weakness occurring in the neck, back, shoulders, forearms, thighs, and hips. Distal weakness may occur but is less common however the trunk often remains strong. Respiratory musculature is also usually involved, thus best evidence supports a combination of resistance and aerobic training. The traditional school of thought was that exercise was safe and effective to improve muscle strength and function in patients with chronic, stable polymyositis, but that it may not be appropriate for patients with active, recent onset inflammatory myopathies. More current research has since shown that an exercise program is both safe and beneficial for patients during the recent onset period of the disease. During acute exacerbations it is recommended that patients utilize pharmacological management to control their inflammation prior to starting their exercise program, and limit their physical activity to normal functional mobility. A key goal of physical therapy is to maintain function and reduce fall risk in PM patients. It is important that patients remain active to maintain function, and it is encouraged that they exercise 5-6 times per week. Strengthening exercises should not occur on back-to-back days, however it is recommended that patients practice “active rest days,” where they focus on ROM, positioning, and relaxation rather than strengthening.

Functional Impairments Secondary to Marked Weakness

• Difficulty with all functional mobility (walking, climbing stairs, etc)

• Difficulty lifting, carrying objects

• Difficulty with ADL’s

• Impaired Balance

• Severe Fatigue

Resistance Training

• Preservation of muscle function

• Avoidance of disuse atrophy

• Light resistance (be cautious with eccentric activity)

• Strengthening of distal musculature, which has the greater potential for strength gains, can contribute greatly to an overall improvement in performance with ADL’s

• Open chain exercises utilize less energy than closed chain, but closed chain exercises yield the greatest outcomes with functional mobility.

• Energy conservation is key (avoid high resistance open chain or aggressive closed chain exercises (Ex: plyometrics))

Aerobic Training

• Cycle ergometer

• Walking

PROM/AAROM/AROM/Stretching

• Contracture prevention

Aquatic Therapy

• Provides ability to mirror functional movements with decreased energy expenditure

• Patient can control resistance of water with modified movement

• Buoyancy assists with posture and lower extremity muscle weakness

• Hydrostatic volume of water increases blood volume in the chest cavity. Patients may experience a significant increase in stroke volume and cardiac output.

• Water turbulence increase blood flow to the surface of the skin

• Therapeutic benefits with a decreased fall risk

Patient education

• A loss of muscle mass results in weakness and fatigue, which may result in the adoption of a sedentary lifestyle. It is very important that patients remain active to avoid disuse atrophy and further muscle weakness.

Differential Diagnosis18

Given the intense treatment regimen that is association with autoimmune disorders it is very important that clinicians make an accurate diagnosis in the cases of inflammatory myopathies. Muscle biopsy is essential for an accurate diagnosis, however it is recognized that there is a pathological overlap in different inflammatory myopathies (ex: polymyositis and dermatomyositis) and other muscle disorders such as congenital muscular dystrophies.

| DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF INFLAMMATORY MYOPATHY |

| Muscular Dystrophies |

| Limb-girdle muscular dystrophy, especially type 2B (dysferlinopathy) |

| Myoshi myopathy (dysferlinopathy) |

| Dystrophinopathy (Becker muscular dystrophy, isolated female manifesting carriers of dystrophinopathy) |

| Facioscapulohumeral dystrophy |

| Metabolic Myopathies |

| Myophophorylase deficiency (McArdle Disease) |

| Phosphofructokinase deficiency |

| Mitochondrial myopathy |

| Acid maltase deficiency |

| Endocrine Myopathies |

| Drug-induced Myopathies |

| D-penicillamine |

| Quinidine |

| Procainamide |

| beta-hydroxy-beta-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors (statins) |

| Interferon alpha |

| Interleukin-2 |

| Motor neuron disease |

| Spinal muscular atrophy (late-onset forms) |

|

Myasthenia gravis |

Case Reports/ Case Studies

Edwards RD, Wiles CM, Roudn JM, Jackson MJ, Young A. Muscle breakdown and repair in polymyositis: a case study. Muscle & Nerve. 1979; 2: 223-8.

Hejazi SMA, Engkasan JP, Qomi MSM. Intensive exercise and a patient in acute phase polymyositis. Journal of Back & Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation. 2012; 25: 231-234.

Bohannon RW, Dvir Z. Distribution and progression of muscle weakness in two cases of polymyositis. Isokinetics & Exercise Science. 2012; 20: 1-4.

Siegel KL; Kepple TM; Stanhope SJ. A case study of gait compensations for hip muscle weakness in idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. Clinical Biomechanics. 2007; 22: 319-26.

Wiesinger GF; Quittan M; Graninger M; Seeber A; Ebenbichler G; Sturm B; Kerschan K; Smolen J; Garinger W. Benefit of 6 monthls long-term physical training in polymyositis/dermatomyositis patients. British Journal of Rheumatology. 1998: 37: 1338-42.

Resources

American Autoimmune Related Disease Association

American College of Rheumatology

Advocating for Chronic Conditions, Entitlements and Social Services (ACCESS)

Myositis Support Group, United Kingdom

National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS)

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS)

The Muscular Dystrophy Association

Recent Related Research (from References

1. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). Polymyositis. function gtElInit() { var lib = new google.translate.TranslateService(); lib.setCheckVisibility(false); lib.translatePage('en', 'pt', function (progress, done, error) { if (progress == 100 || done || error) { document.getElementById("gt-dt-spinner").style.display = "none"; } }); }