Definition/Description

Pott’s Disease, also known as tuberculosis spondylitis, is a rare infectious disease of the spine which is typically caused by an extraspinal infection. Pott’s Disease is a combination of osteomyelitis and arthritis which involves multiple vertebrae.[1] The typical site of involvement is the anterior aspect of the vertebral body adjacent to the subchondral plate and occurs most frequently in the lower thoracic vertebrae. A possible effect of this disease is vertebral collapse and when this occurs anteriorly, anterior wedging results, leading to kyphotic deformity of the spine.[1][2][3] Other possible effects can include compression fractures, spinal deformities and neurological insults, including paraplegia. [1][4]

Prevalence

Incidence

In 2005, there were 8.8 million new patients with tuberculosis (TB) all over the world, and of these, 7.4 million were in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.[5] Involvement of the spine reportedly occurs in less than 1-2% of patients who contract TB. Although the incidence of tuberculosis increased in the late 1980’s to early 1990’s, the total number of cases has decreased in recent years. In the United States, bone and soft tissue tuberculosis accounts for approximately 10% of extrapulmonary TB cases and between 1% and 2% of total cases. Of these cases, Pott’s disease is the most common manifestation of musculoskeletal TB, accounting for approximately 40-50%. Internationally, approximately 1-2% of total tuberculosis cases are attributable to Pott’s disease. [1]

Ethnicity

Data from the United States show that musculoskeletal tuberculosis primarily affects African Americans, Hispanic Americans, Asian Americans, and foreign-born individuals.[1] The number of patients with TB spondylitis in Japan also declined to 233 in 2005 from 734 in 1978 and 276 in 2001.[5]

Gender

Although some studies have found that Pott’s disease does not have sexual predilection, the disease is more common in males. The male to female ratio is reportedly 1.5-2:1.

Age

In the United States and other developed countries, Pott’s disease occurs primarily in adults. In underdeveloped countries which have higher rates of Pott’s disease, involvement in young adults and older children predominates.[1]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation

Spinal Involvement

- Lower thoracic vertebrae is the most common area of involvement (40-50%), followed by the Lumbar spine (35-45%)

- Approximately 10% of Pott’s disease cases involve the cervical spine.[1]

- The thoracic spine is involved in about 65% of cases, and the lumbar, cervical and thoracolumbar spine in about 20%, 10% and 5%, respectively

- The atlanto-axial region may also be involved in less than 1% of cases[2]

Physical Findings

- Localized Tenderness

- Muscle Spasms

- Restricted Spinal Motion

- Spinal Deformity

- Neurological Deficits

Back Pain

Back pain is the earliest and most common symptom. Patients with Pott’s disease usually experience back pain for weeks before seeking treatment and the pain caused by spinal TB can present as spinal or radicular. Although both the thoracic and lumbar spinal segments are nearly equally affected, the thoracic spine is frequently reported as the most common site of involvement. Together, thoracic and lumbar involvement comprise of 80-90% of spinal TB sites.[1]

Neurological Signs

Neurologic abnormalities occur in 50% of cases and can include spinal cord compression with the following:

- Paraplegia

- Paresis

- Impaired sensation

- Nerve root pain

- Cauda equina syndrome[1]

Spinal Deformities

Almost all patients with Pott’s disease have some degree of spine deformity with thoracic kyphosis being the most common.[1]

Constitutional Symptoms

Cervical Spinal TB

Cervical spine TB is a less common presentation occurring in approximately 10% of cases, but is potentially more serious because severe neurological complications are more likely. This condition is characterized by cervical pain and stiffness and symptoms can also include torticollis, hoarseness, and neurological deficits. Upper cervical spine involvement can cause rapidly progressive symptoms and neurologic manifestations occur early, ranging from a single nerve palsy to hemiparesis or quadriplegia. Retropharyngeal abscesses occur in almost all cases. In lower cervical spine insults, the patient can present with dysphagia or stridor.[1]

Presentation in People Infected with HIV

The clinical presentation of spinal tuberculosis in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is similar to that of patients who are HIV negative; however, spinal TB seems to be more common in persons infected with HIV.[1]

Asymptomatic Presentation

62-90% of patients with Pott’s disease are reported to have no evidence of extraspinal tuberculosis, further complicating a timely diagnosis.[1]

Associated Co-morbidities

- Immunosuppressive Disorders

- HIV/AIDS

- TB

- Gastrectomy

- Peptic Ulcer

- Drug Addiction

- Alcoholism

- Malnourishment

- Low Socioeconomic Status

Medications

The duration of treatment is somewhat controversial. Although some studies favor 6 to 9 month course, traditional courses range from 9 months to longer than 1 year. The duration of therapy should be individualized and based on the resolution of active symptoms and the clinical stability of the patient.[1]

The main drug class consists of agents that inhibit growth and proliferation of the causative bacteria. Isoniazid and rifampin should be administered during the whole course of therapy. Additional drugs are administered during the first two months of therapy and these are generally chosen among the first-line drugs which include pyrazinamide, ethambutol, and streptomycin. The use of second-line drugs is indicated in cases of drug resistance.[1]

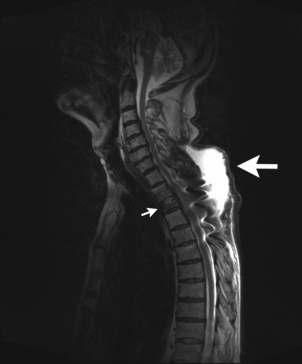

Isoniazid (Laniazid, Nydrazid) The Mantoux Test (Tuberculin Skin Test) Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) Microbiology Studies Radiography CT Scanning MRI MRI of the thoracic spine (T2-weighted, sagittal reconstruction). The dorsal fluid collection suggests a

paravertebral abscess (large arrow) just above the fractured and operated third thoracic vertebra (small arrow)[9]

Biopsy Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) The four primary patterns of involvment in adults are as follows:

1. Paradiscal

2. Anterior Granuloma

3. Central Lesions

4. Appendiceal Type Lesions

The organism that has been identified as causing Pott’s disease is mycobacterium tuberculosis. The primary mode of transmission the bacteria travels to the spine is hematogenously from an extraspinal site of infection. It is common to travel from the lungs in adults but the primary site of infection is often unknown in children.[7][11] The infection has also been found to spread through the lymphatic system.[12] Once being spread, the infection can target vertebrae, intervertebral discs, the epidural or intradural space within the spinal canal and adjacent soft tissue.[6] When the infection is developing, it can spread up and down the vertebral column, stripping the anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments and the periosteum from the front and sides of the vertebral bodies. This results in loss of the periosteal blood supply and distraction of the anterolateral surface of the vertebrae.[3] If a single vertebra is affected, the surrounding intervertebral discs will remain normal. However, if two adjacent vertebrae are affected, the intervertebral disc between them will also collapse and become avascular.[7] Due to the vascularity of intervertebral discs in children, the discs can become a primary site of infection rather than spreading from the vertebrae.[1] Spinal cord compression in Pott’s disease is usually caused by paravertebral abscesses which can also develop calcifications or sequestra within them.[2] If the infection reaches adjacent ligaments and soft tissues, a cold abscess can also form. Abscesses in the lumbar region may descend down the sheath of the psoas to the femoral trigone region and eventually erode into the skin.[1] Other causes of neurological involvement include dural invasion from granulation tissue, sequestrated bone, intervertebral disc collapse or a dislocated vertebra.[2][1][7] Neurological symptoms can occur at any point, including years later as a result of stretching of the spinal cord within the vertebral foramen of the deformed spine.[2] The severity of Pott’s disease varies from one person to another, resulting in different clinical presentations. Possible signs and symptoms that may present are depicted in Table 1 by system.[1][8]

View full drug information: Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values

Injection of a purified protein derivative (PPD). Results are positive in 84-95% of patients with Pott’s disease who are not infected with HIV.[1][8]

ESR may be markedly elevated (>100 mm/h)

Microbiology studies are used to confirm diagnosis. Bone tissue or abscess samples are obtained to stain for acid-fast bacilli (AFB), and organisms are isolated for culture and susceptibility. CT-guided procedures can be used to guide percutaneous sampling of affected bone or soft tissue structures; however, these study findings are positive in only about 50% of the cases.[1]

Radiographic changes associated with Pott’s disease present relatively late. The following are radiographic changes characteristics of spinal tuberculosis on plain radiography:

CT scanning provides much better bony detail of irregular lytic lesions, sclerosis, disk collapse, and disruption of bone circumference. Low contrast resolution provides a better assessment of soft tissue, particularly in epidural and paraspinal areas. CT scanning reveals early lesions and is more effective for defining the shape and calcification of soft tissue abscesses which is common in TB lesions.[1]

MRI is the criterion gold standard for evaluating disk-space infection and osteomyelitis of the spine and is most effective for demonstrating the extension of disease into soft tissue and the spread of tuberculous debris under the anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments. MRI is also called the most effective imaging study for demonstrating neural compression. MRI findings useful to differentiate tuberculosis spondylitis from pyogenic spondylitis include thin and smooth enhancement of the abscess wall and well-defined paraspinal abnormal signal, whereas thick and irregular enhancement of abscess wall and ill-defined paraspinal abnormal signal suggest pyogenic spondylitis. Thus, contrast-enhanced MRI appears to be important in the differentiation of these two types of spondylitis.[1]

Use of a percutaneous CT-guided needle biopsy of bone lesions can be used to obtain tissue samples. This is a safe procedure that also allows therapeutic drainage of large paraspinal abscesses.[1]

PCR techniques amplify species-specific DNA sequences which is able to rapidly detect and diagnose several strains of mycobacterium without the need for prolonged culture. They have also been used to identify discrete genetic mutations in DNA sequences associated with drug resistance.[10]

Etiology/Causes

Systemic Involvement

| Musculoskeletal | Neurological | Cardiovascular | Integumentary | Urogenital | Constitutional Symptoms |

| Vertebral Fractures | Paresthesia | Spinal Artery Infarction | Pressure Ulcers (Secondary) | Bowel Dysfunction | Fever |

| Vertebral Collapse | Paralysis | Avascularity of Intervertebral Discs | Sinus (Secondary to Abscess Rupture) | Bladder Dysfunction | Night Sweats |

| Spinal Ligament Destruction | Paresis | Thrombosis | Cutaneous Fungal Infections | Malaise | |

| Intervertebral Disc Destruction | Abnormal Muscle Tone | Weight Loss | |||

| Paravertebral Abscess | Abnormal Reflexes | ||||

| Osteopenia/Osteoporosis | Cauda Equina Syndrome | ||||

| Bone Sequestrations | Myelomalacia | ||||

| Dislocated Vertebrae | Gliosis | ||||

| Kyphotic Deformity | Syringomyelia | ||||

| Muscle Atrophy | |||||

| Torticollis |

Medical Management (current best evidence)

Treatment goals

- Confirm Diagnosis

- Eradicate Infection

- Identify and Remove Causative Pathogen

- Recover/Maintain Neurological Function

- Recover/Maintain Mechanical Spine Stability

- Correct or Prevent Spinal Deformity and Possible Sequelae

- Functional Return to Activities of Daily Living[3][8]

Treatment Techniques

- Anti-Tuberculosis Chemotherapy

- Surgical Drainage of Abscess

- Surgical Spinal Cord Decompression

- Surgical Spinal Fusion

- Spinal Immobilization

Predictors of Good Prognosis

- Partial Cord Compression

- Short Duration of Neural Complications

- Early Onset Cord Involvement with Delayed Neural Complications

- Young Age

- Good General Condition[6]

Effective chemotherapy for Pott’s disease is the gold standard and must be started at the early stages of the disease.[6] Radical ventral debridement, fusion and reconstruction of the vertebral column remains the gold standard of surgical treatment for tuberculosis spondylitis.[8]

Multiple surgical approaches have been conducted to correct the spinal deformity seen in Pott’s disease with varying results. Laminectomy failed to address the anterior component of the disease process and spinal instability. Posterior fusion has been successful at reducing kyphosis but preoperative infection and high levels of kyphosis have resulted in many fusion failures. An anterior approach, used by Hodgson and Stock, has also been used with great success.[6]

Various surgical techniques are utilized based on which area of the spine is affected. In the upper cervical spine, a transoral or extreme lateral approach is taken which typically requires concurrent occipito-cervical fusion to prevent collapse, instability and delayed deformity. Midcervical lesions are often treated with standard anterior cervical approaches and achieve excellent results. Transsternal, transmanubrial, or lateral extracavitary approaches are conducted in patients with involvement of the lower cervical/upper thoracic spine. In the thoracic spine surgeons make use of transthoracic, extraplural anterolateral or extended posterolateral approaches. The posterolateral method ismore often utilized in severe cases of kyphosis due to the natureof the spinal deformity and ease of access to the spine. However, surgical correction of a severe kyphotic deformity (>30 degrees) will often require a posterior technique that is complex and technically demanding. Surgical morbidity and mortality can be significant for these technically demanding procedures with ;an 8-10% incidence post correction neurological complications. Surgical procedures in the lumbar spine are typically performed through a lateral retroperitoneal approach which is the preferred method compared to an anterior or retroperitoneal procedure.[8]

Surgery done during the active course of the disease is much safer with a faster and better response. Moreover, the importance of early diagnosis, start of appropriate treatment and its continuation for adequate duration along with the proper counseling of the patient and family members with the timely surgical intervention is the key for the success in achieving a good outcome.[6]

Physical Therapy Management (current best evidence)

Patients with Pott’s disease often undergo spinal fusion or spinal decompression surgeries to correct their structural deformity and prevent further neurological complications. There are no established guidelines which dictate treatments that will yield positive outcomes in such patients. However, treatment regimens should address each patient individually, focusing on any impairments, functional limitations and/or disabilities with which they present.

PT Managment Post-Spinal Decompression Surgery

- Spinal Stabilization Exercises

- Maitland

- Back School

- Exercise and Strengthening

When compared with other physical therapy treatments and self-managment, spinal stabilization exercises were found to produce significantly more positive ratings in global outcomes. Pain and disability, however, did not show significant improvement when compared to the other two treatment options.[13]

PT Managment Post-Spinal Fusion Surgery

- TENS (Transcutaneous Electrical Neuromuscular Stimulation)

- Aquatic Therapy

- Overground Training (Walking Program)

- Aerobic Exercise

- Trunk Strengthening

Studies examining the use of TENS have shown higher frequencies are more effective in decreasing neuropathic pain. Aerobic exercise, PT, and trunk strengthening interventions have all attained significant decreases in pain, psychological distress and disability.[14]

Differential Diagnosis

- Actinomycosis

- Blastomycosis

- Brucellosis

- Candidiasis

- Cryptococcosis

- Histoplasmosis

- Metastatic Cancer, Unknown Primary Site

- Miliary Tuberculosis

- Multiple Myeloma

- Mycobacterium Avium-Intracellulare

- Mycobacterium Kansasii

- Nocardiosis

- Paracoccidioidomycosis

- Sarcoidosis

- Septic Arthritis

- Spinal Cord Abscess

- Spinal Stenosis

- Spondylolisthesis

- Tuberculosis

- Vertebral Osteomyelitis[1]

Case Reports

Sarangapani A, Fallah A, Provias J, Jha NK. Resources

General Tuberculosis Information

Tuberculosis Drug Information

Recent Related Research (from References