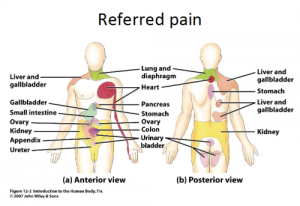

Definition/Description

Referred pain is pain perceived at a location other than the site of the painful stimulus/ origin.[1] It’s the result of a network of interconnecting sensory nerves. This network supplies many different tissues. When there is an injury at one place in the network, this pain can be interpreted in the brain to radiate nerves. And can give pain elsewhere in the related areas of the network. [2]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

Several neuroanatomic and physiologic theories state that nociceptive dorsal horn and brain stem neurons receive convergent inputs from various tissues. Therefore, higher centres cannot identify correctlythe actual input source. Most recently, the models have included newer theories in which plasticity of dorsalhorn and brainstem neurons plays a central role. During the past decades, a systematic attempt to chart referred musculoskeletal pain areas in humans has been made.[1]

Nerve fibers of higher regions sensory input such as the skin and nerve fibers of lower sensory input such as the stomach come together at the same level of the spinal cord. When there is an important stimulus of the lower sensory input the brain can interpreted this as coming from the higher regions. Because the brain is not used to this important input of the lower regions. So the pain well be located in the related dermatome of the same spinal segment. [3]

The most famous example of this topic is the pain felt of cardiac ischemia felt in the neck and and down the left shoulder and arm. The referred pain apparantely occurs because multiple primary sensory neurons converge on a single ascending tract. When the painfull stimuli arise in visceral receptors the brain is unable to distinguish visceral signals from the more common signals arise from somatic receptors. Asresult it interprets the pain as coming from the somatic regions rather than the viscera.[4] Imman and Saunders suggested that referred pain followed the distribution of sclerotomes (muscle, fascia, and bone) more frequently than it followed the classical dermatomes.[1] Sensory manifestations of clinical and experimental muscle pain are seen as diffuse aching pain in the muscle, pain referred to distant somatic structures, and modifications in superficial and deep tissue sensibility in the painful areas.[1]Peripheral input from the referred pain area is involved but nota necessary condition for referred pain. Hypothetically, convergence of nociceptive afferents on dorsal horn neurons may mediate referred pain.[1])

Neuro Physiological Theories

Several neuro physiological theories have been suggested[1]:

• Convergence-projection theory

This is the most acceptable explanation in which the pain is caused by meeting the afferent information of the visceral organs and those of somatic origin on the same segment. This causes hyperreactivity of the dorsal horn neurons which is interpreted as coming from the same dermatom.

• Convergence-facilitation theory

• Axon-reflex theory

• Hyperexcitabillity theory

• Thalamic convergence theory

Epidemiology /Etiology.

The pain is derived from a different area then the pain area. Common cause of referred pain are pain radiating from; a spine, sacroiliacal joint, viscera, tumors, infections or from associated manifestations.[5][6]

We also notice that the pain is always related to the nerve of this particular area. For example when the ninth cranial nerve (glossopharyngeal nerve) is involved the pain is felt deep in the ear. This in contrast to the more superior located pain when the trigeminal nerve is involved. (6)

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation:[1]

Size of referred pain is related to the intensity and duration of ongoing/evoked pain.

Temporal summation is a potent mechanism for generation of referred muscle pain.

Central hyperexcitability is important for the extent of referred pain.

Patients with chronic musculoskeletal pains have enlarged referred pain areas to experimental stimuli. The proximal spread of referred muscle pain is seen in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain and very seldom is it seen in healthy individuals.

Modality-specific somatosensory changes occur in referred areas, which emphasize the importance of using a multimodal sensory test regime for assessment.

Diagnostic Procedures

Studies of clinical pain are limited by bias because of cognitive, emotional, and social aspects of the disease. Pain is a multidimensional and highly individualized perception that is very difficult to quantify and to validate in the clinical setting. In experimental pain, the researchers have the possibility to control the intensity of the stimulus ,its duration and also its modality.[1] With experimental pain we can also asses the psychological evoked response or qualitatively (using, for example, the McGill Pain Questionnaire) or quantitatively (using, for example, visual analogue scores).[1] (level of evidence 2B)

Endogenous methods are not suitable to induce referred pain, because they are characterized by a high response rate en are very suitable for studying general pain states.(1) But they have also the disadvantage because they involve several or all muscle groups. Therefore it’s better to use exogenous models.[1] (level of evidence 2B)

The exogenous model that is the most used is the intramuscular infusion of hypertonic saline. After the infusion, referred pain will be felt in structures at a distance from the infusion site.[1] There it will appear with a delay of approximately 20 seconds in comparison with local pain [7]. The patient will experience this pain as being diffuse and unpleasant.[8](8)

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|

Advantages and disadvantages of intramuscular infusion of hypertonic saline.

Also other alogenic substances such as bradykinin, serotonin, capsaicin and substance P can be used to cause referred pain.[9][10][1][2][3]

Another method to cause referred pain is to use intramuscular electrical stimulation. There is a significantly higher stimulus intensity needed elicit referred pain in comparison with local pain, and there is a significantly positive correlation been found among the stimulus intensity and the local pain and referred pain intensity ratings.[1][4] (level of evidence 2B)

Results are showing us that there is a significant correlation between the size of local pain and referred pain areas and the local sensation/pain and referred sensation/pain intensity ratings.[1][4] Also Increased nociceptive input that will go to the dorsal horn or the brainstem neurons, which generates an expansion of receptive fields, may be responsible for the expansion of referred areas that are detected during an increased intramuscular stimulation. [4]

Examination

Several explanations regarding the divergent results obtained when an area of referred pain is anesthetized have been offered [4][1]: (level of evidence 2B)

1. The variation in the number of structures (skin, subcutis, fascia, muscle, tendons, ligaments, and bone) that is anesthetized. This is the most important criteria, because referred pain areas and, especially visceral referred pain, are commonly found to be located in the deep tissues in which complete anaesthesia of a referred pain area is difficult.[1][4]

2. The duration and level of local pain. [1][4]

3. The site of the local pain (skin, viscera, and deep structures). [1][4]

4. Whether sensory changes (hypersensitivity) occur at the referred pain site.[1][4]

Medical Management

Several studies have found that the area of the referred pain correlated with the intensity and duration of the muscle pain, which parallels the observations for cutaneous secondary hyperalgesia. [6][5]

The most effective treatment for chronic musculoskeletal pain is the using of NMDA-receptor antagonists (ketamin), this gives us better results than using conventional morphine management. [1][5]. (Level of evidence 2B) (Grade of recommendation C)

Also the applying of an eutectic mixture of local anesthetica on the skin, just above the referred pain area, reduced the referred pain intensity with 22.7%. [6] (Grade of recommendation B) A similar result was found after that ethyl chloride was sprayed onto a saline-induced referred pain area.[7]

There are two techniques to block all afferents from the referred pain area: (level of evidence 2B) (Grade of recommendation C)

1. Differential nerve blocking with an inflated tourniquet between the site of stimulation and the corresponding distal referred area

2. Intravenous regional analgesia

By this the referred pain intensity was reduced by 40.2 %

Other ways to treat the pain are:[9] (level of evidence 1A) (Grade of recommendation A)

1. Acupuncture [9]

2. Osteopathic manual medicine techniques[9]

3. Trigger point injections[9][10][1]

4. Laser therapy[1]

Superficial dry needling is the most effective in combination with stretching [2]

Physical Therapy Management

The pain that comes with myofascial pain syndrome is referred pain. So this is a therapy to treat the referred pain that causes the myofascial pain syndrome.

1. Dry needling[9][10][1][3] (level of evidence 1A)(grade of recommendation A)

2. Massage [9][1] 5level of evidence 1A. (Grade of recommendation A)

3. Application of heat or ice [9] (Level of evidence 1A) (Grade of recommendation A)

4. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation [9][10][1]( (Level of evidence 1A) (Grade of recommendation A)

5. Ethyl chloride spray and stretch technique [9][10][1](Level of evidence 1A) (Grade of recommendation A)

6. Ultrasound [9][1] (Level of evidence 1A) (Grade of recommendation A)

7. Manual methods [9](Level of evidence 1A) (Grade of recommendation A)

8. Exercise[9][1] ((Level of evidence 1A) (Grade of Recommendation A)

Resources

Primary Resources

Alvarez D.J. et al, Trigger points: Diagnosis and Management, Am Fam Physician, 2002, 15, 65, p. 653-660.

Arendt-Nielsen L, Svensson P (2001). “Referred muscle pain: basic and clinical findings”. Clin J Pain 17 (1): 11–9.

Babenko V. et al, Experimental human muscle pain and muscular hyperalgesia induced by combinations of serotonin and bradykinin, Pain 1999, 82, p. 1-8.

Edwards J. et al, Superficial dry needling and active stretching in the treatment of myofascial pain, Acupunct med, 2003,21,p. 80-86.

Graven-Nielsen T. et al, Stimulus-response functions in areas with experimentally induced referred muscle pain- a psychophysical study, Brain Res, 1997, 744,p. 121-8.

Graven-Nielsen T. et al, Quantification of local and referred muscle pain in humans after sequential i.m. injections of hypertonic saline, Pain 1997,69, p. 111-7.

Han S.C. et al, Myofascial pain syndrome and trigger-point management, Reg Anesth, 1997, 22, p. 89 -101.

Ilbuldu E. et al, Comparison of laser, dry needling, and placebo laser treatments in myofascial pain syndrome, Photomed laser surg, 2004, 22, p.306-311.

Jensen K. et al, Pain and tenderness in human temporal muscle induced by bradykinin and 5 hydroxytryptamine, Peptides, 1990 , 11, p. 1127-32.

Kalichman L. et al, Dry needling in the management of musculoskeletal pain, JABFM, 2010, 23, p. 640 -646.

Laursen R.J. et al, Quantification of local and referred pain in humans induced by intramuscular electrical stimulation, EurJ Pain, 1997, 1, p.105-13.

Laursen RJ et al., Referred pain is dependent on sensory input from the periphery: a psycophysical study, Eur J Pain, 1997, 1, p 105-13.

Laursen R. et al, The effect of compression and regional anaesthetic block on referred pain intensity in humans, Pain, 1999, 80, p.257-63.

Marcgettini P et al, Pain from excitation of identified muscle nociceptors in humans, Brain Res, 1996, 740, p. 4-412.

Pedersen-Bjergaard U. et al., Algesia and local responses induced by neurokinin A and substance P in human skin and temporal muscle, Peptides, 1989, 10, p.1147-52.

Sörensen J. et al, Hyperexcitability in fibromyalgia, J Rheumatol, 1998, 25, p. 152-5.

Whitty C.W.M. et al, Some aspects of referred pain, Lancet, 1958, 2, p.226-31.

Witting N. et al, Intramuscular and intradermal injection of capsaicin: a comparison of local and referred pain. Pain 2000, 84, p 407-12.

Secondary Resources

Ari B.Y., Low Back Pain with Referred Pain, Recent Related Research (from References