Rehabilitation is the restoration of optimal form (anatomy) and function (physiology).[1]

The noun rehabilitation comes from the Latin prefix re-, meaning “again” and habitare, meaning “make fit.” It is a process designed to minimize the loss associated with acute injury or chronic disease, to promote recovery, and to maximize functional capacity, fitness and performance.[1]

Musculoskeletal injuries are an inevitable result of sport participation. Football has the highest incidence of catastrophic injuries, with gymnastics and ice hockey close behind. Tissue injury from sports can be classified as macrotraumatic and microtraumatic.[2]

- Macrotraumatic injuries are usually due to a strong force – such as a fall, accident, collision or laceration – and are more common in contact sports such as football and rugby. These injuries can be primary (due to direct tissue damage) or secondary (due to transmission of forces or release of inflammatory mediators and other cytokinesis).[2]

- Microtraumatic injuries are chronic injuries that result from overuse of a structure such as a muscle, joint, ligament, or tendon. This type of injury is more common in sports such as swimming, cycling and rowing.[2]

The process of rehabilitation should start as early as possible after an injury and form a continuum with other therapeutic interventions. It can also start before or immediately after surgery when an injury requires a surgical intervention.[1]

Rehabilitation Plan

The rehabilitation plan must take into account the fact that the objective of the patient (the athlete) is to return to the same activity and environment in which the injury occurred. Functional capacity after rehabilitation should be the same, if not better, than before injury.[1]

The ultimate goal of the rehabilitation process is to limit the extent of the injury, reduce or reverse the impairment and functional loss, and prevent, correct or eliminate altogether the disability.[1]

Multidisciplinary Approach

The rehabilitation of the injured athlete is managed by a multidisciplinary team with a physician functioning as the leader and coordinator of care. The team includes, but is not limited to, sports physicians, physiatrists (rehabilitation medicine practitioners), orthopaedists, physiotherapists, rehabilitation workers, physical educators, coaches, athletic trainers, psychologists, and nutritionists. The rehabilitation team works closely with the athlete and the coach to establish the rehabilitation goals, to discuss the progress resulting from the various interventions, and to establish the time frame for the return of the athletes to training and competition.[1]

Communication is a vital factor. A lack of communication between medical providers, strength and conditioning specialists, and team coaches can slow or prevent athletes from returning to peak capability and increase the risk of new injuries and even more devastating reinjuries.[3]

Principles

Principles are the foundation upon which rehabilitation is based. Here are seven principles of rehabilitation, which can be remembered by the mnemonic: ATC IS IT.[4]

A: Avoid aggravation. It is important not to aggravate the injury during the rehabilitation process. Therapeutic exercise, if administered incorrectly or without good judgment, has the potential to exacerbate the injury, that is, make it worse.[4]

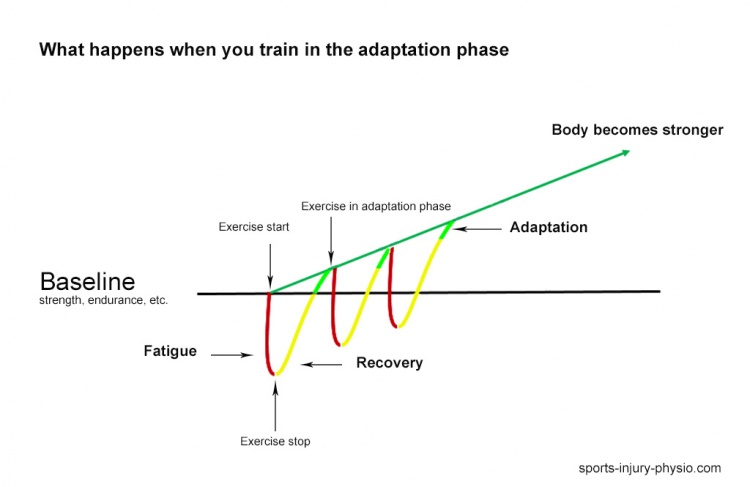

T: Timing. The therapeutic exercise portion of the rehabilitation program should begin as soon as possible—that is, as soon as it can occur without causing aggravation. The sooner patients can begin the exercise portion of the rehabilitation program, the sooner they can return to full activity. Following injury, rest is sometimes necessary, but too much rest can actually be detrimental to recovery.[4]

C: Compliance. Without a compliant patient, the rehabilitation program will not be successful. To ensure compliance, it is important to inform the patient of the content of the program and the expected course of rehabilitation.[4]

I: Individualization. Each person responds differently to an injury and to the subsequent rehabilitation program. Even though an injury may seem the same in type and severity as another, undetectable differences can change an individual’s response to it. Individual physiological and chemical differences profoundly affect a patient’s specific responses to an injury.[4]

S: Specific sequencing. A therapeutic exercise program should follow a specific sequence of events. This specific sequence is determined by the body’s physiological healing response.[4]

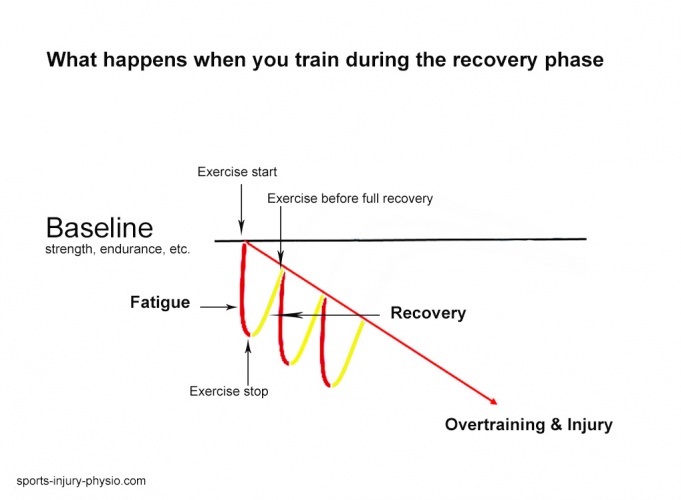

I: Intensity. The intensity level of the therapeutic exercise program must challenge the patient and the injured area but at the same time must not cause aggravation. Knowing when to increase intensity without overtaxing the injury requires observation of the patient’s response and consideration of the healing process.[4]

T: Total patient. It must be considered the total patient in the rehabilitation process. It is important for the unaffected areas of the body to stay finely tuned. This means keeping the cardiovascular system at a preinjury level and maintaining range of motion, strength, coordination, and muscle endurance of the uninjured limbs and joints. The whole body must be the focus of the rehabilitation program, not just the injured area. Providing the patient with a program to keep the uninvolved areas in peak condition, rather than just rehabilitating the injured area, will help to better prepare the patient physically and psychologically for when the injured area is completely rehabilitated.[4]

Components

Regardless of the specifics of the injury, however, here are fundamental components that need to be included in all successful rehabilitation programs:

Pain Management

Medications are a mainstay of treatment in the injured athlete – both for their pain relief and healing properties. It is recommended that they need to be used judiciously with a distinct regard for the risks and side effects as well as the potential benefits, which include pain relief and early return to play. Therapeutic modalities play a small, but important, part in the rehabilitation of sports injuries. They may help to decrease pain and edema to allow an exercise-based rehabilitation programme to proceed. By understanding the physiological basis of these modalities, a safe and appropriate treatment choice can be made, but its effectiveness will ultimately depend upon the patient’s individualized and subjective response to treatment. [1]

Flexibility and Joint ROM

Injury or surgery can result in decreased joint ROM mainly due to fibrosis and wound contraction.[1] Besides that, it is common for post-injury flexibility to be diminished as a result of muscle spasm, inflammation, swelling and pain. In addition to impacting the injured area, this also affects the joints above and below the problem, and creates motor pattern issues.[5] Flexibility training is an important component of rehabilitation in order to minimize the decrease in joint ROM. Also, a variety of stretching techniques can be used in improving range of motion, including PNF, ballistic stretching and static stretching.[1]

Strength and Endurance

Injuries to the musculoskeletal system could result in skeletal muscle hypotrophy and weakness, loss of aerobic capacity and fatigability. During rehabilitation after a sports injury it is important to try to maintain cardiovascular endurance. Thus regular bicycling, one-legged bicycling or arm cycling, an exercise programme in a pool using a wet vest or general major muscle exercise programmes with relatively high intensity and short rest periods (circuit weight training) can be of major importance.[1]

Proprioception and Coordination

Proprioception can be defined as ‘a special type of sensitivity that informs about the sensations of the deep organs and of the relationship between muscles and joints’.[1] Loss of proprioception occurs with injury to ligaments, tendons, or joints, and also with immobilization.[2] Proprioceptive re-education has to get the muscular receptors working, in order to provide a rapid motor response (Scott et al. 2000).[1] Restoration of proprioception is an important part of rehabilitation.[2] The treatment has to be adapted to each individual, considering the type of injury and the stress to which the athlete will be exposed when practicing his or her sport.[1]

Coordination can be defined as ‘the capacity to perform movements in a smooth, precise and controlled manner’. Rehabilitation techniques increasingly refer to neuromuscular re-education. Improving coordination depends on repeating the positions and movements associated with different sports and correct training. It has to begin with simple activities, performed slowly and perfectly executed, gradually increasing in speed and complexity. The technician should make sure that the athlete performs these movements unconsciously, until they finally become automatic.[1]

Functional Rehabilitation

All rehabilitation programs must take into account, and reproduce, the activities and movements required when the athlete returns to the field post-injury.[5] The goal of function-based rehabilitation programmes is the return of the athlete to optimum athletic function. Optimal athletic function is the result of physiological motor activations creating specific biomechanical motions and positions using intact anatomical structures to generate forces and actions.[1]

The use of Orthotics

The use of orthotic devices to support musculoskeletal function and the correction of muscle imbalances and inflexibility in uninjured areas should receive the attention of the rehabilitation team.[1] Appropriate orthotic application will result in restraint forces that oppose an undesired motion (Kilmartin & Wallace 1994). A complete orthotic prescription should include the patient’s diagnosis, consider the type of footwear to be used, include the joints it encompasses and specify the desired biomechanical alignment, as well as the materials for fabrication. Communication with the orthotist,who will fabricate or fit the brace, is of utmost importance in order to obtain a good clinical result.[1]

Psychology of Injury

Injury is more than physical; that is, the athlete must be psychologically ready for the demands of his or her sport.[3] The most immediate emotional response at the point of injury is shock. It’s degree may range from minor to significant, depending upon the severity of the injury. It is important to note that denial itself is an adaptive response that allows an individual to manage extreme emotional responses to situational stress.[2] Many individuals assist athletes through the recovery process and can foster psychological readiness, but they can also identify those who are physically recovered but require more time or intervention to be fully prepared to return to competition. Thus, rehabilitation and recovery are not purely physical but also psychological.[3]

Mental skills in sports are often viewed as part of an individual’s personality and something that cannot be taught. Many physicians feel that injured athletes either have or do not have the mental toughness to progress through rehabilitation. Mental skills, however, can be learned. One example for this is to provide proper goal setting, which has very important role in sports rehabilitation, because they can enhance recovery from injury. Goal setting needs to be measurable and stated in behavioral terms. The research indicates that goals should be challenging and difficult, yet attainable. It is important for physicians to help them focus on short-term goals as a means to attain long-term goals. For example, to set daily and weekly goals in rehabilitation process which will end in long-term goal like returning to play after an injury. It is important for sports medicine physicians to assist patients in setting goals related to performance process rather than outcomes, such as returning to play.[2]

Stages of Rehabilitation

Initial Stage of Rehabilitation

This phase lasts approximately 4-6 days.[6] The body’s first response to an injury is inflammation.[5] It’s main function is to defend the body against harmful substances, dispose of dead or dying tissue and to promote the renewal of normal tissue.[7] The goals during the initial phase of the rehabilitation process include limitation of tissue damage, pain relief, control of the inflammatory response to injury, and protection of the affected anatomical area. The pathological events that take place immediately after the injury could lead to impairments such as muscle atrophy and weakness and limitation in the joint range of motion. These impairments result in functional losses, for example, inability to jump or lift an object. The extent of the functional loss may be influenced by the nature and timing of the therapeutic and rehabilitative intervention during the initial phase of the injury. If functional losses are severe or become permanent, the athlete now with a disability may be unable to participate in his/her sport.[1]

The physiotherapist is usually the professional in charge of this phase although the process may be started by a medical doctor.[6]

Control pain and swelling[4]

Primary treatment in initial phase of rehabilitation is RICE.[5] It is the term that stands for Rest, Ice, Compression and Elevation. RICE can be used immediately and 24 to 48 hours after many muscle strains, ligament sprains, or other bruises and injuries.[8]

Therapeutic modalities and medications are used to create an optimal environment for injury repair by limiting the inflammatory process and breaking the pain-spasm cycle. Use of any modality depends on the supervising physician’s exercise prescription, as well as the injury site, and type and severity of injury. In some cases, a modality may be indicated and contraindicated for the same condition. For example, thermotherapy (heat therapy) may be contraindicated for tendinitis during the initial phase of the exercise program. However, once acute inflammation is controlled, heat therapy may be indicated. Frequent evaluation of the individual’s progress is necessary to ensure that the appropriate modality is being used.[3]

Despite the fact that rapid return to competition is crucial, rest is necessary to protect the damaged tissue from additional injury. Therefore, exercise involving the injured area is not recomended during this phase, although there are a few exceptions such as the tendinopathy protocols used to rehabilitate Achilles and patella tendon injuries.[5][9] However, it is important to realize that a quick return to function relies on the health of other body tissues.

The power, strength, and endurance of the musculoskeletal tissues and the function of the cardiorespiratory system must be maintained.[5] Athlete needs to understands the reasons for following a particular treatment regime or exercise program, as well medical professional’s advice should be sought before embarking on any regime as more harm can be done than good if carried out incorrectly.[9]

Active range of motion is performed under one’s own control, while passive range of motion occurs when another person or device produces the movement.[2] If movement of the injured limb is not contraindicated, isolated exercises that target areas proximal and distal to the injured area may be permissible provided that they do not stress the injured area. Examples include hip abduction and rotation exercises following knee injury or scapula stabilizing exercises following glenohumeral joint injury.[5] Isometric exercises are used for strengthening when range of motion is restricted or needs to be avoided due to the fracture or acute inflammation of a joint. Otherwise, isotonic strengthening can begin within the painless arc of joint motion.[2]

Intermediate Stage of Rehabilitation

This phase lasts from day 5 to 8-10 weeks.[6] After the inflammatory phase, the body begins to repair the damaged tissue with similar tissue, but the resiliency of the new tissue is low. Repair of the weakened injury site can take up to eight weeks if the proper amount of restorative stress is applied, or longer if too much or too little stress is applied.[5]

Joint ROM and Muscle Conditioning[4]

The goals during the second phase of rehabilitation include the limitation of the impairment and the recovery from the functional losses. Early protected motion hastens the optimal alignment of collagen fibers and promotes improved tissue mobility. A number of physical modalities are used to enhance tissue healing. Exercise to regain flexibility, strength, endurance, balance, and coordination become the central component of the intervention. To the extent that these impairments and functional losses were minimized by early intervention, progress in this phase can be accelerated. Again, the maintenance of muscular and cardiorespiratory function remains essential for the uninjured areas of the body. The strength and conditioning professional has considerable expertise to offer the other members of the sports medicine team regarding selection of the appropriate activities.[5]

Possible exercise forms during this phase include strengthening of the uninjured extremities and areas proximal and distal to the injury, aerobic and anaerobic exercise, and improving strength and neuromuscular control of the involved areas[5]:

- Isometric exercise may be performed provided that it is pain free and otherwise indicated. Submaximal isometric exercise allows the athlete to maintain neuromuscular function and improve strength with movements performed at an intensity low enough that the newly formed collagen fibers are not disrupted.[5]

- Isokinetic exercise can be an important aspect of strengthening following injury. This type of exercise uses equipment that provides resistance to movement at a given speed (e.g., 60°/s or 120°/s).[5]

- Isotonic exercise involves movements with constant external resistance and the amount of force required to move the resistance varies, depending primarily on joint angle and the length of each agonist muscle. Isotonic exercise uses several different forms of resistance, including gravity (i.e., exercises performed without equipment, with gravitational effects as the only source of resistance), dumbbells, barbells, and weight-stack machines. The speed at which the movement occurs is controlled by the athlete; movement speed can be a program design variable, with more acute injuries calling for slower movement and the later phases of healing amenable to faster, more sport-specific movement.[5]

- Specific types of exercises exist to improve neuromuscular control following injury and can be manipulated through alterations in surface stability, vision, and speed. Mini-trampolines, balance boards, and stability balls can be used to create unstable surfaces for upper and lower extremity training. Athletes can perform common activities such as squats and push-ups on uneven surfaces to improve neuromuscular control.[5]

- Exercises may also be performed with eyes closed, thus removing visual input, to further challenge balance.[5]

Finally, increasing the speed at which exercises are performed provides additional challenges to the system. Specifically controlling these variables within a controlled environment will allow the athlete to progress to more challenging exercises in the next stage of healing.[5]

Advanced Stage of Rehabilitation

This phase begins at around 21 days and can continue for 6-12 months.[6] The outcome of the previous phase is the replacement of damaged tissue with collagen fibers. After those fibers are laid down, the body can begin to remodel and strengthen the new tissue, allowing the athlete to gradually return to full activity.[5] This phase of rehabilitation represents the start of the conditioning process needed to return to sports training and competition. Understanding the demands of the particular sport becomes essential as well as communication with the coach. This phase also represents an opportunity to identify and correct risk factors, thus reducing the possibility of re-injury.[1]

Functional Training

The combination of clinic-based and sport-specific functional techniques will provide an individualized, sport-specific rehabilitation protocol for the athlete.[10] Rehabilitation and reconditioning exercises must be functional to facilitate a return to competition. Examples of functional training include joint angle-specific strengthening, velocity-specific muscle activity, closed kinetic chain exercises, and exercises designed to further enhance neuromuscular control. Strengthening should transition from general exercises to sport-specific exercises designed to replicate movements common in given sports.[5] Cross-training is encouraged, especially with activities that do not produce any symptoms from the injury.[2]

It is essential that the rehabilitation and training be sufficiently vigorous to prepare the injured tissue for the demands of the game.[6] With each increase in activity, signs of recurring pain or weakness should trigger a slowdown or a reversal to a tolerable level of activity.[2] The player will have returned to game during this phase and will have ceased physiotherapy or individual rehabilitation while this process is still continuing.[6] Unrestricted sports activity is not allowed until all of these steps have been completed and full-effort sports-specific activity is tolerated without symptoms.[2]

Return to Sport

At some point in the recovery process, athletes return to strength and conditioning programs and resume sport-specific activities in preparation for return to play. The transition is important for several reasons. First, although the athlete may have recovered in medical terms (ie, improvements in flexibility, range of motion, functional strength, pain, neuromuscular control, inflammation), preparation for competition requires the restoration of strength, power, speed, agility, and endurance at levels exhibited in sport.[3]

Return to play is defined as the process of deciding when an injured or ill athlete may safely return to practice or competition. Early return to training and sport are considered sensible goals if the rate of return is based on the affected muscle, the severity of the injury and the position of the athlete.[6]

Criteria for return to play must emphasize gradual return to sport-specific functional progressions. Sport-specific function occurs when the activations, motions and resultant forces are specific and efficient for the needs of that sport. Sport-specific functional rehabilitation should focus on restoration of the injured athlete’s ability to have sport-specific physiology and biomechanics to interact optimally with the sport-specific demands.[1] That means that they need to be replicated at the same speed, on the same surface and with the same level of fatigue to be truly effective.[5]

Once a athlete has been medically cleared to return-to-play there are some fundamental steps that need to be followed[6]:

- The athlete has to fulfill the fitness standards of the team he is returning to.

- The athlete needs to pass some skill specific tests applicable to his playing position.

- The player may then begin practicing with the team.

- Exposure to the match situation should be gradual, with the match time gradually increasing.

There are simple guidelines which need to be developed by each team with contributions and support from each member of the medical team.[6]

Monitoring

Regarding these aspects from the text above, there are several problems: are all the mechanic parameters of the performance (force, velocity, power) regained at that time? Are there any ways to conduct the rehabilitation program in order to obtain better parameters and so the return to the sports activity to be safely done? Which could be the most suitable evaluation methods in order to be sure about the athletes well-training? [8]

Monitoring athlete well-being is essential to guide training and to detect any progression towards negative health outcomes and associated poor performance. Objective (performance, physiological, biochemical) and subjective measures (mood disturbance, perceived stress and recovery and symptoms of stress) are all options for athlete monitoring.[9] Appropriate load monitoring can aid in determining whether an athlete is adapting to a training program and in minimizing the risk of developing non-functional overreaching, illness, and/or injury.[2]

In order to gain an understanding of the training load and its effect on the athlete, a number of potential markers are available for use. There are a number of external load quantifying and monitoring tools, such as power output measuring devices, time-motion analysis, as well as internal load unit measures, including perception of effort, heart rate, blood lactate, and training impulse. Other monitoring tools used by high-performance programs include heart rate recovery, neuromuscular function, biochemical/hormonal/immunological assessments, questionnaires and diaries, psychomotor speed, and sleep quality and quantity.[2] Coaching staffs and administrative personnel must work to ensure that care can be provided at all points of the rehabilitation process, especially when funding dictates the need to hire personnel capable of addressing injuries at multiple levels. A clear understanding of the injury and of the interventions from each provider is vital to an efficient and successful return to play.[3]

Appropriate monitoring of training load can provide important information to athletes and coaches; however, monitoring systems should be intuitive, provide efficient data analysis and interpretation, and enable efficient reporting of simple, yet scientifically valid, feedback. If accurate and easy-to-interpret feedback is provided to the athlete and coach, load monitoring can result in enhanced knowledge of training responses, aid in the design of training programs, provide a further avenue for communication between support staff and athletes and coaches and ultimately enhance an athlete’s performance.[2]