Definition/Description

Scheuermann’s disease, also known as juvenile osteochondrosis, is named after Holger Werfel Scheuermann. The disease is characterized by a structural kyphosis of the thoracic or thoracolumbar spine.[1] The disease can range from mild to a severe life-threatening deformity. Some people have no problems (mild threatening) but others will experience problems such as increasing curved spine, pain, neurological, heart or lung problems. In addition, it has been suggested that between 20 to 30% of patients with Scheuermann’s disease also have scoliosis. In more serious cases, the combination is sometimes known as kyphoscoliosis. First described in 1920, Scheuermann’s disease is the most common cause of kyphotic deformity in adolescents.[2]

There are two major forms of Scheuermann’s kyphosis. The thoracic form is most common and has an apex between T7-T9. Secondly, the thoracolumbar form can occur with an apex between T10-T12 and is more likely to continue into adulthood.[2][3] Lumbar kyphosis is also possible; however, it is non-progressive and resolves with rest, activity modification and time. Lumbar kyphosis is associated with repetitive activities involving axial loading of the immature spine.[4] Thus, it is not considered within the scope of this article.

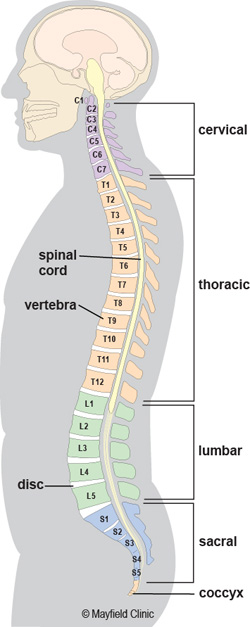

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

The spine of an adult is naturally shaped in an S-curve. The cervical and lumbar regions are concave (lordosis), and the thoracic and sacral regions are convex (kyphosis). According to the Scoliosis Research Society, the thoracic spine has a kyphosis between 20 to 40 degrees. A spinal deformity is considered when the curve is greater (or lesser) as mentioned degrees.

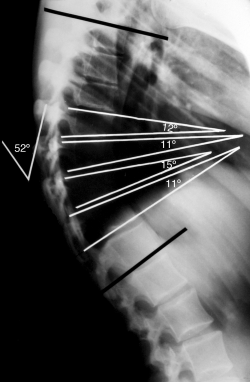

Scheuermann’s disease is a structural deformity of the vertebral bodies and spine. The kyphosis of the thoracic region will be around 45 to 75 degrees. Also there will be vertebral wedging greater than five degrees of 3 or more adjacent vertebrae. [5] The wedge shaped bodies characterize the rigid hyperkyphosis we see in Scheuermann’s disease. The hyperkyphosis can be compensated by a lumbar and cervical hyperlordosis.

Epidemiology /Etiology

The disease mostly develops during puberty and is seen equally in both sexes.[2] Depending on which criteria is used, 5 to 40% of the population has this anomaly. In the United States the disease occurs in 0,4 to 8 % of the general population .[5] A study by Armbrecht et al. found the prevalence of Scheuermann’s disease in Europe to be 8% in persons aged 50 years and above. [6] Many theories have been proposed for the etiology of Scheuermann’s disease, including mechanical, metabolic, and endocrinologic causes, but the real cause is still unclear.

The etiology is unknown, but is thought to be multifactorial.[7] Some of the theories proposed include juvenile osteoporosis, malabsorption, infection, endocrine disorders and biomechanical factors including a shortened sternum.[7][8] In addition, a strong hereditary pattern has been identified through autosomal dominance with a high degree of penetrance and variable expressivity.[4] Furthermore, genetic studies with monozygotic and dizygotic twins have shown that heredity is 74%. [9]

The role of height and weight of children with Scheuermann had been studied by Fotiadis et al. Patients who are affected at age 13-16 years, are taller than comparable peers and have advanced skeletal versus chronologic age. Some of them also have affected limb lengths. [10]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation

According to Sorenson [5], Scheuermann’s kyphosis is characterized by following criteria. Three or more adjacent vertebrae must be wedged 5° or more and there must be no evidence of congenital, infectious or traumatic disorders of the spine.

Patients who have Scheuermann’s disease have progressive structural kyphosis throughout the adolescent period. The diagnosis is mostly made between 12 and 17 years.[11] The first sign will be an altered posture. Further there will be rarely other symptoms. A typical presentation will include a forward head position, rounded shoulders, and possible flexion contractures of the shoulder and hip joint. Also shortened hamstrings, lumbar lordosis and a protuberant abdomen can be detected. As the disease progresses, there will be more symptoms of the disease like:

- possible, intermittent, back pain and aching

- muscle stiffness and fatigue, especially at the end of the day

- decreased flexibility of the torso

In severe cases, heart and lung function can be impaired or severe neurological symptoms can occur. These symptoms are extremely rare.

Patients with Scheuermann’s disease may also complain of inability to participate in physical exercise, work and activities of daily living secondary to pain or the presence of their deformity negatively affecting their cosmetic appearance.[12]

Typically, the pain increases with activity and is relieved by rest. The deformity of the spine will be relatively unmovable, unlike in postural kyphosis.[11] It is also possible to see cutaneous skin pigmentation at the area of greatest curvature due to skin friction on chair backs.[12]

The natural history of Scheuermann’s kyphosis is unclear, with conflicting reports as to the severity of pain and physical disability. [13]

Differential Diagnosis

Diagnostic Procedures

Sorenson [5] proposed in 1964 a diagnosis based on two criteria:

- 3 or more adjacent vertebrae wedged 5° or more

- no evidence of congenital, infectious or traumatic disorders of the spine

Another way to diagnose is with the Drummond’s criterion or Bradford’s criterion. Drummond’s criterion is 2 wedged vertebrae. Bradford’s criterion is ≥ 1 vertebrae wedged ≥ 5°. This criterion leads to earlier diagnosis and treatment which can help minimize deformity.[15]

Scheuermann’s disease is diagnosed with lateral radiographs. On the radiographs three parameters can be analyzed: [16]

- [16]

Besides vertebral wedging, other radiographic findings are irregularity of the vertebral endplates, herniation through the endplates (Schmorl’s nodes), narrowing of the intervertebral disc spaces, and lengthening of the vertebral bodies. [12]

Scheuermann’s disease can be evaluated by other tools such as CT scans or magnetic resonance imaging. [17]

Outcome Measures

Following self-reported outcome measures can be used after an operative treatment [18] or for untreated Scheuermann’s disease as well [12]:

- Scoliosis Research Society Instrument (SRSI): This questionnaire can be used for follow- up of an individual to see if the patient reports improvements in level of activity, pain, personal relationships etc.

- Back pain and disability scores: Examination

The most significant feature of patients with Scheuermann’s disease is the thoracic kyphosis. Often the kyphosis is accompanied by a lumbar and/or cervical hyperlordosis. The cervical lordosis can be increased with a protrusion of the head. The shoulders mostly are positioned anteriorly. These abnormalities can be accompanied by a mild to moderate scoliosis. Patients with Scheuermann’s disease are well muscled compared to patients with postural kyphosis. [3]

The examination consist of:- Postural assessment: examination of the posture from anterior, posterior and lateral view

- Neurological screening: [4] rarely the spinal cord can be stretched over the posterior aspect of the vertebral bodies at the apex of the curvature which may cause neurological signs of impending paraplegia with clonus and hyperreflexia.[14]

- [7]

- Muscle length testing: the disease can be accompanied by tightness of the M. Pectoralis, [2][3]

- Range of motion: Flexibility of the extremities and spine can identify impairments and track changes over time.[7]

- Muscle strength testing: strength of the abdominals, core, trunk extensors and gluteal muscles must be assessed

Medical Management (current best evidence)

Surgical treatment of Scheuermann’s kyphosis is rarely necessary but is the only way to significantly improve the deformity. [7] The choice of treatment in Scheuermann’s kyphosis is based on the severity and progression of the curve, the age of the person, and the symptomatology present. (level of evidence: 2A)

Operative management has been advocated for adolescents with:

- progressive kyphosis (over 70°)

- progression despite bracing

- intractable back pain despite conservative treatment

- unacceptable cosmetic deformity [7] possibly leading to self-consciousness and poor self-esteem [2] (level of evidence: 2A and 1A)

- progressive neurological symptoms [19] (level of evidence: 1B)

Surgical options include posterior spinal arthrodesis with or without anterior spinal release by thoracotomy or video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS).[7](level of evidence: 2A)

Surgical treatment in adolescents and young adults should be considered if there is documented progression, refractory pain, loss of sagittal balance, or neurologic deficit. [13] (level of evidence: 1A)

Physical Therapy Management (current best evidence)

Conservative treatment of Scheuermann’s kyphosis remains controversial. This can be divided by bracing techniques and physiotherapy exercises. Both have conflicting reports to their effectiveness. [20] The treatment differs between skeletally immature and skeletally mature patients. (level of evidence: 4)

Bracing

Bracing is widely regarded as being efficacious in the treatment of Scheuermann’s kyphosis in the skeletally immature patient with a kyphotic curve of more than 45°. Many studies have proven that for patients who are already skeletally mature, bracing is not an effective treatment. [21]Bracing has been used primarily for the treatment of deformity; the results of brace treatment for relieving pain have not yet been published. Bracing is also used to decrease stress on the anterior wall of the vertebral body. [2][22] (level of evidence: 1B)

The overall results of brace treatment seem reproducible and promise a permanent correction of vertebral deformity. [16] (level of evidence: 2B)According to Lowe, brace treatment is almost always successful in patients with kyphosis between 55 degrees and 80 degrees if the diagnosis is made before skeletal maturity. A greater kyphosis is almost never treated successfully without surgery in symptomatic patients.

- Bracing therapy has a few shortcomings:

as the bracing time increases, the probability to develop low back pain increases - in adolescents the compliance is usually low

Ideally, bracing should begin at the onset of puberty, be worn for approximately 2 years, and removed at the end of skeletal maturity. [4][5]Braces should be worn 22-24 hours daily for the first 12- 18 months, and the part time (at night) until the patient reaches skeletal maturity. (level of evidence: 5)

Braces that could be used for the treatment of Scheuermann’s kyphosis are:- Milwaukee brace

- Gschwend brace

- Kyphologic brace

- SpinoMed brace

Other bracing strategies have been attempted such as the use of a soft brace but this however has not shown to be successful. With a soft brace no correction can be achieved in rigid curvatures.

Physiotherapy

According to Bezalel et al (2014), the literature rarely mentions physical therapy as an effective treatment for Scheuermann’s disease. Although the little evidence, it is often used as the first choice of treatment. [13] (level of evidence: 1A)

Treatment of the Scheuermann’s disease depends on the severity and the progression of the disease, the presence or absence of pain and the age of the patient.

Physical therapy for postural improvement is often recommended, focusing on hamstring and pectoralis stretching and trunk extensor strengthening as well as improving function.[23] These exercises can be effective when the thoracic spine has not developed a relevant stiffness and when the sagittal curve is not too high: [19] (level of evidence: 1B)

Scheuermann’s disease in adults is regarded to be a different entity from that of the teenager because the major manifestation is pain and not aesthetic quality. The functional rehabilitation on an outpatient basis is the favoured treatment and referral for surgery or dorso-lumbar braces is rare.

According to Pizzutillo, effective interventions for adolescents with postural kyphosis include exercises to relieve lower extremity contractures and strengthen abdominal musculature, coupled with practiced normal posture standing and sitting. Several studies reported that adolescents with Scheuermann’s Kyphosis who have undergone physical therapy showed improvement in Cobb angle and respiration. [24][25][26][27][28] Adolescents with a kyphosis less than 60° are mostly treated with only flexibility-exercises. [20] (level of evidence: 4)Skeletally immature patients with Scheuermann’s kyphosis benefit from a similar exercise program but also require the use of a spinal orthosis. Bracing of the spine in patients with Scheuermann’s kyphosis results in permanent correction of vertebral deformity. [23] (level of evidence: 1B)

The kyphotic posture can be treated with the Schroth method. This program is developed in the 1920s in Germany by Katharina Schroth. [29]The trunk is divided into three regions (cervical, thoracic and lumbar segments). The program consist of special exercises to correct the positions of these three blocks in the sagittal plane. The exercises are combined with self-elongation of the vertebral column, a correction of breathing techniques and a re-education of the neuromuscular system to improve postural perception. A mirror can be used to synchronize the corrective moments and to improve the postural perception. During the exercises, the patient uses corrective active trunk muscle forces and learns to maintain an erect posture. Later the corrected posture must be maintained throughout activities of daily living. Cooperation and motivation are important factors of success of the Schroth method. All exercises must be tailored to the individual patient. [20] (level of evidence: 4)

Bezalel et al concluded that the Schroth therapy could decrease the thoracic curve angle of patients with Scheuermann’s Kyphosis. The efficacy and effectiveness of this method should be investigated in further research. [20](level of evidence: 4)

Examples of Schroth exercises are:

Berdishevsky investigated the effect of an intensive outpatient rehabilitation and bracing program in an adult patient with Scheuermann’s disease. The physical therapy consist of exercises based on the Schroth program and on the Principles of Correction of the Barcelona Scoliosis Physical Therapy School (BSPTS). [30] (level of evidence: 4) There are five Principles of Correction:

- Trunk elongation and expansion

- Symmetrical sagittal straightening: identical exercises must be performed for both sides of the trunk (right and left):

Bilateral thoracic expansion in a posterior to anterior (PA) direction to reduce the thoracic hyperkyphosis

Bilateral lumbar expansion in an anterior to posterior (AP) direction to reduce the hyperlordotic low back - Shoulder traction: the traction enhances the expansion of the thorax and corrects the spine

- Correction of breathing: it allows the subject to feel an increased expansion in his/her initially collapsed regions. The goal is to expand the thorax in a back-to-front and a lateral direction.

- Muscle activation by increasing tension: to achieve the best possible correction, muscle balance, stabilization and to increase the proprioceptive input. It helps to integrate the ‘corrected body schema’ in the brain.

Berdishevsky concluded that intensive physical therapy with these methods and combined with bracing (SpinoMed brace) was successful to treat an adult patient with Scheuermann’s kyphosis. The patient compliance with the exercises and the brace is important for a positive result. [30] (level of evidence: 4)

For Scheuermann’s patients extension sports are advised: such as gymnastics, aerobics, swimming, basketball, cycling and hyperextension exercises. Some sports should be discouraged: like sports associated with jumping, marked stress and functional overuse of the back. [31][32] (level of evidence: 4)

Postoperative physical therapy is necessary and must contain breathing exercises, mobilizations and strengthening exercises. [1] (level of evidence: 1A)

More clinical trials are necessary to evaluate the effectiveness of conservative interventions, especially different exercises and manual therapies. These should also be combined/compared with braces. [13](level of evidence: 1A)

Clinical Bottom Line

Scheuermann’s kyphosis can present as a progressive kyphotic deformity with possible pain in adolescents aged 12-17 years. Treatment of the Scheuermann’s disease depends on the severity and the progression of the disease, the presence or absence of pain and the age of the patient. Early diagnosis and treatment with bracing or a spinal orthosis can help to stop the kyphotic process and results in permanent correction of vertebral deformity. Physical therapy (Schroth therapy, Principles of Correction of the Barcelona Scoliosis Physical Therapy School, …) is recommended for postural improvement. Physical therapy can be combined with bracing. More evidence for the efficiency of these therapies is needed.

Key Research

- Bezalel, Tomer, and Leonid Kalichman. “Improvement of clinical and radiographical presentation of Scheuermann disease after Schroth therapy treatment.” Journal of bodywork and movement therapies 19.2 (2015): 232-237

- Berdishevsky, Hagit. “Outcome of intensive outpatient rehabilitation and bracing in an adult patient with Scheuermann’s disease evaluated by radiologic imaging—a case report.” Scoliosis and spinal disorders 11.2 (2016): 40.

Resources

Deutchman: Schroth Method Exercises for Scoliosis:

Strott: The Scheuermann’s Disease Fund:

Spine Universe. Scheuermann’s Kyphosis (Scheuermann’s disease): abnormal curvature of the spine. Available on:

Recent Related Research (from [13] summarized the current knowledge related to the diagnosis and the treatment of Scheuermann’s disease. They revealed a major genetic contribution to the etiology of the kyphosis. They concluded that it is difficult to determine if a brace treatment is effective, since it is impossible to predict which kyphotic curves will progress. Finally they concluded that despite the little evidence for physical therapy, it is frequently used as the first choice of treatment for Scheuermann’s disease. (level of evidence: 1A)

Bezalel et al (2015), (20) further investigated Scheuermann’s disease. He evaluated the effectiveness of Schroth therapy. He concluded that this method could be effective in preventing and even improving the thoracic curve angle. (level of evidence: 4)

Berdishevsky et al (2016), [30] investigated the effectivity of Schroth therapy combined with bracing in an adult patient with Scheuermann’s disease. He concludes that intensive physical therapy combined with bracing could be successful in the treatment of an adult patient with Scheuermann’s disease. The patient has a reduced kyphosis and less vertebral rotation. The quality-of-life-score showed a significant improvement, also pain and trunk deviation were diminished. (level of evidence: 4)

A recent study of Gokce et al. (2016), [33] evaluated 20 patients with plain radiography and MRI for a period of 5 years. The conclusion of this longitudinal study was that Scheuermann Disease can be seen in typical and atypical patterns. Several pathologies of the back and the spinal cord can accompany the Scheuermann disease which can make it atypical. (level of evidence: 4)

References

- ↑ 1.01.1 TG Lowe. Scheuermann disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:940-945. LOE: 1A

- ↑ 2.02.12.22.32.42.5 Papagelopoulos P, Mavrogenis A, Savvidou O, Mitsiokapa E, Themistocleous G, Soucacos P. Current concepts in Scheuermann’s kyphosis. Orthopedics 2008;31(1):52-60. LOE: 2B

- ↑ 3.03.13.2 Lowe TG, Line BG. Evidence based medicine: analysis of Scheuermann kyphosis. Spine 2007;32(19 suppl):115-19. LOE: 3A

- ↑ 4.04.14.24.3 Weiss H, Turnbull D. Kyphosis (physical and technical rehabilitation of patients with Scheuermann’s disease and kyphosis). In: JH Stone, M Blouin, editors. International Encyclopedia of Rehabilitation. LOE : 5

- ↑ 5.05.15.25.35.4 Sorenson KH. Scheuermann’s Juvenile Kyphosis. Cophenagen: Munksgaard; 1964. LOE: 5

- ↑ Armbrecht G, Felsenberg D, Ganswindt M, et al. Vertebral Scheuermann’s disease in Europe: prevalence, geographic variation and radiological correlates in men and women aged 50 and over. Osteoporos Int. 2015 Oct. 26 (10):2509-19. LOE: 2C

- ↑ 7.07.17.27.37.47.57.67.7 Hart E, Merlin G, Harisiades J, Grottkau B. Scheuermann’s thoracic kyphosis on the adolescent patient. Orthopaedic Nursing 2010;29(6):365-71. LOE: 2A

- ↑ Fotiadis E, Grigoriadou A, Kapetanos G, Kenanidis E, Pigadas A, Akritopoulos P, et al. The role of sternum in the etiopathogenesis of Scheuermann disease of the thoracic spine. Spine 2008;33(1):21-4. LOE: 2B

- ↑ Damborg F, Engell V, Andersen M, Kyvik K, Thomsen K. Prevalence, concordance, and heritability of Scheuermann kyphosis based on a study of twins. J Bone Joint Surg 2006;88(10):2133-6. LOE: 4

- ↑ Fotiadis E, Kenanidis E, Samoladas E, Christodoulou A, Akritopoulos P, Akritopoulou K. Scheuermann’s disease: focus on weight and height role. Eur Spine J. 2008 May. 17(5):673-8. LOE: 3B

- ↑ 11.011.1 Robert J. Moore. The vertebral endplate: disc degeneration, disc regeneration. Eur Spine J. Aug 2006; 15(Suppl 3): 333–337. LOE: 5

- ↑ 12.012.112.212.3 Ristolainen, L., et al. “Untreated Scheuermann’s disease: a 37-year follow-up study.” European Spine Journal 21.5 (2012): 819-824. LOE: 2B

- ↑ 13.013.113.213.313.4 Bezalel, Tomer, et al. “Scheuermann’s disease: Current diagnosis and treatment approach.” Journal of back and musculoskeletal rehabilitation 27.4 (2014): 383-390. LOE: 1A

- ↑ 14.014.114.2 Lemire JJ, Mierau DR, Crawford CM, Dzus AK. Scheuermann’s juvenile kyphosis. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1996;19(3):195-201. LOE: 2B

- ↑ Weiss et al. The practical use of surface topography: following up patients withfckLRScheuermann’s disease. PEDIATRIC REHABILITATION, 2003 LOE: 2B

- ↑ 16.016.116.2 Aulisa, Angelo G., et al. “Conservative treatment in Scheuermann’s kyphosis: comparisonfckLRbetween lateral curve and variation of the vertebral geometry.” Scoliosis and spinalfckLRdisorders 11.2 (2016): 33. LOE: 2B

- ↑ Ali, Raed M., Daniel W. Green, and Tushar C. Patel. “Scheuermann’s kyphosis.” CurrentfckLRopinion in pediatrics 11.1 (1999): 66-69. LOE: 5

- ↑ Poolman, R., H. Been, and L. Ubags. “Clinical outcome and radiographic results afterfckLRoperative treatment of Scheuermann’s disease.” European Spine Journal 11.6 (2002): 561-fckLR569. LOE: 3B

- ↑ 19.019.1 Goodman CC, Fuller KS. Pathology Implications for the Physical Therapist. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Elsevier Inc; 2009. LOE: 5

- ↑ 20.020.120.220.3 Bezalel, Tomer, and Leonid Kalichman. “Improvement of clinical and radiographical presentation of Scheuermann disease after Schroth therapy treatment.” Journal of bodywork and movement therapies 19.2 (2015): 232-237. LOE: 4

- ↑ Spine health. Conditions. Scoliosis. Juvenile disorder. www.spine-health.com/conditions/scoliosis/juvenile-disc-disorder. LOE: 5

- ↑ de Mauroy J, Weiss H, Aulisa A, Aulisa L, Brox J, Durmala J, et al. 7th SOSORT consensus paper: conservative treatment of idiopathic and Scheuermann’s kyphosis. Scoliosis 2010;5:9. LOE: 1B

- ↑ 23.023.1 Weiss et al. Review Brace treatment for patients with Scheuermann’s disease – a review of the literature and first experiences with a new brace design. Scoliosis 2009 LOE: 1B

- ↑ Weiß, Hans-Rudolf, Jörg Dieckmann, and Hans-Jürgen Gerner. “Outcome of in-patient rehabilitation in patients with M. Scheuermann evaluated by surface topography.” Studies in health technology and informatics (2002): 246-249. LOE: 4

- ↑ Weiß, Hans-Rudolf, Jörg Dieckmann, and Hans-Jürgen Gerner. “Effect of intensive rehabilitation on pain in patients with Scheuermann’s disease.” Studies in health technology and informatics (2002): 254-257. LOE: 2B

- ↑ Ball, J. M., et al. “Spinal extension exercises prevent natural progression of kyphosis.” Osteoporosis International 20.3 (2009): 481. LOE: 4

- ↑ Montgomery, Stephen P., and Wendell E. Erwin. “Scheuermann’s Kyphosis-Long-Term Results of Milwaukee Brace Treatment.” Spine 6.1 (1981): 5-8. LOE: 1A

- ↑ Zaina, F., et al. “Review of rehabilitation and orthopedic conservative approach to sagittal plane diseases during growth: hyperkyphosis, junctional kyphosis, and Scheuermann disease.” European Journal of physical and rehabilitation medicine 45.4 (2009): 595-603. LOE: 1A

- ↑ Weiss, Hans-Rudolf. “The method of Katharina Schroth-history, principles and current development.” Scoliosis 6.1 (2011): 17. LOE: 4

- ↑ 30.030.130.2 Berdishevsky, Hagit. “Outcome of intensive outpatient rehabilitation and bracing in an adult patient with Scheuermann’s disease evaluated by radiologic imaging—a case report.” Scoliosis and spinal disorders 11.2 (2016): 40. LOE:4

- ↑ Damborg F, Engell V, Andersen M, Kyvik K, Thomsen K. Prevalence, concordance, and heritability of Scheuermann kyphosis based on a study of twins. J Bone Joint Surg 2006;88(10):2133-6. LOE: 4

- ↑ Sturm, Peter F., J. Crawford Dobson, and Gordon WD Armstrong. “The surgical management of Scheuermann’s disease.” Spine 18.6 (1993): 685-691. LOE: 4

- ↑ Gokce, Erkan, and Murat Beyhan. “Radiological imaging findings of scheuermann disease.” World Journal of Radiology 8.11 (2016): 895. LOE: 4