Introduction

Cervical arterial dysfunction (CAD) is an umbrella term used in manual therapy and physiotherapy to cover a range of vascular pathologies which may lead to [1] and has been adopted by the International Federation of Orthopaedic Manual Physical Therapists (IFOMPT) in their 2013 document:

The IFOMPT document provides clinical reasoning and physical examination guidance for clinicians and highlights the need for manual therapy clinicians to be cognisant with the concept and details of CAD. Much of the information on this page is detailed further in the IFOMPT document.

Note: The term should not be confused with cervical arterial dissection which is also referred to via the acronym CAD. This relates to a single, specific pathology (see below).

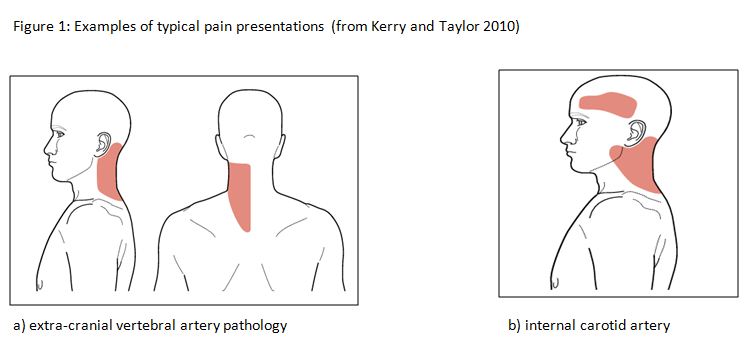

CAD itself is not a specific pathology diagnosis. Thus, there is a variation in clinical presentation which is dependent on the structure involved, the pathological mechanism and the stage at which the dysfunction presents. CAD is of relevance to clinicians due to the fact the pain is often an early presentation of many types of arterial dysfunction, Fig 1[2].

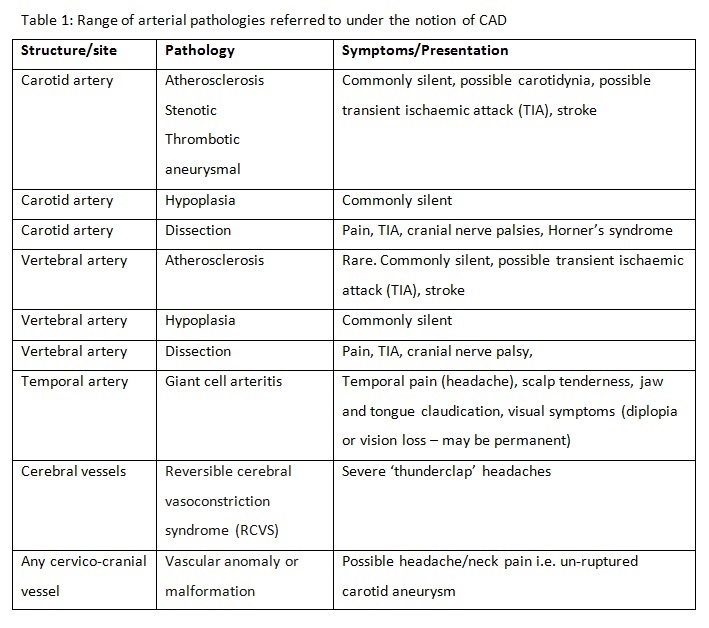

Later ischaemic manifestations of CAD, such as cranial nerve dysfunction and brain ischaemia, may be latent and develop hours, days or weeks after onset. Table 1 (below) details the range of presentations and associated clinical symptoms.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

The contemporary approach to risk assessment of the cervical spine incorporates a [2]. This differs from previous paradigms by considering the complete intra and extra cranial arterial supply of the cervico-cranial region, and the wide range of associated pathologies. This includes the anterior cervical arterial system i.e. the common carotid artery (CCA) its related branches (internal and external) and pathologies, in addition to the previously considered posterior circulation, i.e. the vertebrobasilar arterial system (VBA).

The vertebrobasilar arterial (VBA) system and Epidemiology

Care must be taken when discussing the epidemiology. CAD is an umbrella term, and as such it is necessary to consider the epidemiology of each pathology. First, the correct population must be identified, relative to the inquiry. For example, the rate of VBI following cervical manipulation is a different matter to the prevalence of VBI in a population. Such data may help the clinician to judge the likelihood of a patient with head/neck pain having CAD. This is a difficult question to answer with existing data as the concept is new. Nevertheless, to help judge the size of the problem, the following data can be considered.

As stroke / TIAs are a primary concern, the following data sets the scene. Ischaemic stroke is the 3rd most common cause of death in western populations[3], and in US/EU populations has a crude incidence of between 81 and 267 cases per 100,000/year[4]. Most of these events are related to atherosclerotic disease processes, with a minority related to non-atherosclerotic dissection events or mechanical phenomena.

Historic obsession in manual therapy with the vertebral artery and dissection in particular, means that the only data available pertains to dissection of the vertebral artery following manipulation. This data is of course important but represents a very small part of a big picture. No consideration has previously been given to the other potential structures and pathologies that may result in delayed diagnosis or adverse events.

If just these data are considered, then the best estimates from the most recent studies suggest that the risk of vertebral artery dissection following manipulation is around 6:100,000, compared to a normal occurrence of around 1:100,000[5] This relates only to dissection events, There are no known data for the rate of ICA-related events following treatment due to the fact that this notion has only recently been introduced. Further, there are no known systems for collecting and collating such adverse events, so the actual rates are unknown.

A third way of framing the epidemiology is in terms of the proportion of people visiting physiotherapists who may have or develop CAD. This is the number of people with head and/neck pain who have a CAD-related pathology as the source and cause of that pain. Unlike haemorrhagic events where a headache is most often overshadowed by focal signs, ischaemic and atherosclerotic pathologies very often present with neck pain and headache as their first and most overt symptom.

Headache attributed to cranial or cervical vascular disorder is formally classed as a secondary headache by the latest International Headache Society criteria[6]. The prevalence of this, and this as a proportion of all headaches, is unknown, but very likely to be epidemiologically small. Furthermore, it should be remembered that migraineous headache itself is a known risk factor for CAD.

The epidemiology related to identifying those neuromusculoskeletal patients who may be more at risk of developing CAD is of course integrated with the above data, but even more complex to specifically identify. CAD-model reasoning would involve an understanding of the above data, together with an understanding of the societal level of vascular disease – atherosclerosis is the biggest single cause of death and morbidity in the western world – integrated with assessment of features of presentation and an individuals risk factors (see below).

Summary – the overall chance of a patient presenting with head and neck pain having a CAD-related pathology is very small. Presence of specific signs and symptoms, together with collation of known risk factors will influence this a priori probability judgment.

CAD is an umbrella term covering a broad spectrum of potential pathologies. These range from pre-existing underlying anatomical anomalies, Horner’s Syndrome), blindness, stroke, or at worst, death. A spectrum of potential patho-mechanisms of ischaemia and related symptoms are covered in table 1.

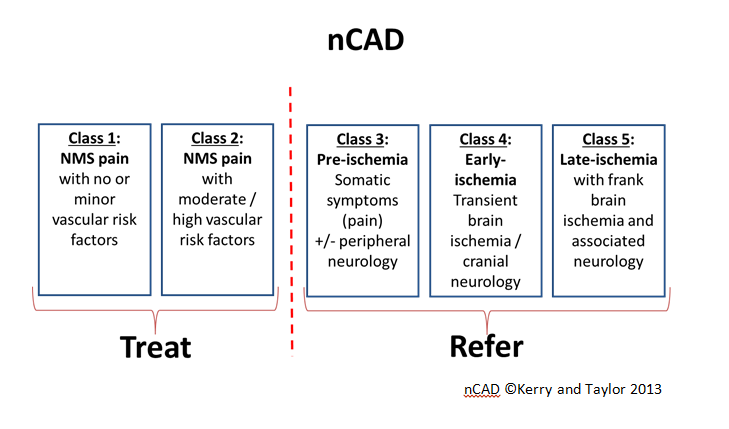

The key thing for the clinician is to be able to risk assess adequately for CAD prior to physical examination or exercise intervention. As pain may be the only initial complaint and a decision must be made as to whether this is simply a benign neuro-musculoskeletal (NMS) complaint or the pathogenesis of a neuro-vascular problem. Table 1 describes the range of possibilities. The following risk factors are associated with an increased risk of either internal carotid or vertebrobasilar arterial pathology and should be thoroughly assessed during the patient history: The role of the clinician is not to aim for a precise ‘diagnosis’ of a specific condition. Rather, the CAD model facilitates the clinician in making a probability judgements on either the presence or not of any CAD-related pathology, or the likelihood of impending risk related to planned neuromusculoskeletal assessment or intervention. Figure 2[7]. provides a profiling system is designed to organise the clinicians thought processes regarding classification of patients Pathological Process

Differential diagnosis

Risk factors and classification model

Examination