Introduction

According to the European guidelines created by Vleeming and colleagues,[1] “Pelvic girdle pain (PGP) generally arises in relation to pregnancy, trauma, arthritis and osteoarthritis. Pain is experienced between the posterior iliac crest and the gluteal fold, particularly in the vicinity of the sacroiliac joints (SIJ). The pain may radiate in the posterior thigh and can also occur in conjunction with/or separately in the symphysis. The endurance capacity for standing, walking, and sitting is diminished. The diagnosis of PGP can be reached after exclusion of lumbar causes. The pain or functional disturbances in relation to PGP must be reproducible by specific clinical tests”[1]

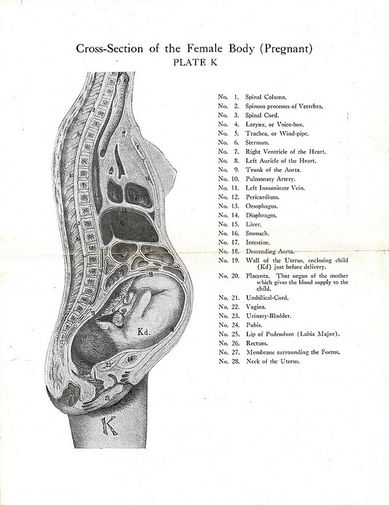

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

The pelvis is composed of the sacrum, ilium, ischium and pubis. The pelvic bone consists the pubic symphysis and the sacroiliac joint.

Sacroiliac Joints

The sacroiliac joints allow for the transfer of forces between the spine and the lower extremity.[2] To read more about the function of the sacroiliac joints review: Force and Form Closure

Pelvic Floor

The pelvic floor muscles have two primary functions in females. The muscles:[3]

- support the abdominal viscera (bladder, intestines, uterus) and the rectum

- control the mechanism for continence for the urethral, anal and vaginal orifices[3]

Etiology

The etiology of pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain has not been clearly established in the literature.[4] However, the cause of this pain is believed to be multi-factorial and may be related to hormonal, biomechanical, traumatic, metabolic, genetic and degenerative factors.[5][6][7]

Hormonal

Women produce increased quantities of the hormone relaxin during their pregnancy. Relaxin increases ligament laxity in the pelvic girdle (and in other parts of the body) in preparation for the labour process. Increased ligament laxity may cause a small increase in the range of motion at the pelvis. If this increase in motion is not complimented by a change in neuromotor control (e.g., muscles around the pelvis act to improve stability), it is possible that pain may occur.[1] However, the link between relaxin and pelvic girdle pain during pregnancy has not been established in the literature.[6][7] Research to date also does not support the idea that an increase in the range of motion at the pelvis causes pain.[1][8][9]

Biomechanical

As pregnancy progresses, the gravid uterus increases load on the spine and pelvis. To accommodate for the growth of the uterus the pubic symphysis must soften and laxity in the pelvic ligaments increases. The uterus shifts forward which changes the maternal centre of gravity and the orientation of pelvis.[10] This change in centre of gravity may cause stress or a change in load on the lower back and pelvic girdle.[6][11][7] This change in load can result in compensatory postural changes (e.g., an increase in lumbar lordosis).[6][11][7]

Risk Factors

The risk factors for developing pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain are:

- a previous history of low back pain or pelvic girdle pain.[12][7]

- a previous trauma to the pelvis or back.[12][7]

- physical demanding work (e.g., twisting and bending the back several times per hour per day).[1][13][14][15][16]

- multiparity – may play a causal role in the development of pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain[17]

Epidemiology

Pelvic girdle pain may begin around the 18th week of pregnancy and appears to peak between the 24th and 36th week.[18] Pelvic pain affects approximately 50% of women during pregnancy.[13] 25% of the women who experience pelvic girdle pain report having severe pain and 8% report pain that causes severe disability.[19]

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation of pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain can vary from patient to patient and can change over the course of the patient’s pregnancy.[13] Since the causes of pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain are multi-factorial and, it is important to incorporate a biopsychosocial approach to the diagnosis and treatment of this pain.

Subjective History

Common symptoms related to pregnancy-related pelvic pain include:

- a difficulty walking quickly and covering long distances[1][20][13]

- pain/discomfort/difficulty during sexual intercourse[20][13]

- pain/discomfort during sleep and/or a difficulty turning over in bed[13][21]

- decreased ability to perform housework[13][21]

- decreased ability to engage in activities with children[13]

- difficulty sitting[21]

- difficulty standing for 30 minutes or longer[21]

- pain in single leg stance i.e., climbing stairs[21]

- inability or difficulty running (postnatal) due to pain[21]

- decreased ability for mother-child interactions[14]

- pain/discomfort with weight bearing activities[11]

Pain

The onset of pain may occur around the 18th week of pregnancy and reaches peak intensity between the 24th and 36th week of pregnancy. The pain typically resolves by the third month in the postpartum period.[22][7]

Location

Pelvic girdle pain typically presents near the sacroiliac joints and/or gluteal area or anteriorly near the symphysis pubis[13]. The reported pain may radiate into the patient’s groin, perineum or posterior thigh but does not mimic a typically sciatic nerve root distribution.[23][24] The location of the pain may vary throughout the course of the pregnancy.[25] A pain distribution diagram can be a useful tool in identifying the patient’s pain and to help distinguish pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain from [26]

Nature and intensity of pain

Pelvic girdle pain may be described as a stabbing,[27][28] dull, shooting, or burning sensation.[28] The intensity of pain on a 100 mm visual analogue scale averages around 50-60 mm.[25][24]

Muscle Function and Perception

- postpartum women may present with reduced hip abduction and adduction force[29] which may be related to fear of pain/movement.[29]

- women may reported a feeling of “catching” in their upper leg during ambulation[28] and/or report feeling the lack the ability to move their legs during the active straight leg test[30] which may suggest nervous system involvement.[13]

- altered gait coordination – women with postpartum pelvic girdle pain can present with a coupling between pelvic and thoracic rotations during gait (pelvic and thoracic rotations in the same direction occur at the same time) which has been proposed as a nervous system strategy used to cope with motor problems.[31]

Pelvic Girdle Pain Examination

Before a diagnosis of pelvic girdle pain is reached potential lumbar spine pain and/or dysfunction should be ruled out.[1] Once the lumbar spine is ruled out the sacroiliac joint, the symphysis pubis, and the pelvis should be assessed.

Sacroiliac joint

Symphysis Pubis

Functional Pelvic Test

Diagnostic Procedures

During pregnancy diagnostic imaging using radiation is contraindicated.[26] Ultrasound imaging and/or MRIs may be used for certain interventions and/or surgical planning or to rule out the presence of serious medical conditions.[34]

Outcome Measures

The Pelvic Girdle Questionnaire (PGQ)[35] was developed to evaluate impairments and/or the functional limitations caused my pelvic girdle pain during pregnancy and in the postpartum period.[35] The PGQ has been found to significantly discriminated participants who were pregnant from participants who were not pregnant.[36]

Clinton and colleagues[26] recommend using the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) and the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) when assessing and treating patients with pelvic girdle pain. Using these scales in your clinical practice can help provide you with a broader understanding of your patient’s ability to mental process their pain and how their pain is affecting their daily activities. Currently only the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire-Physical Activity sub-scale has been validated for use during pregnancy.[36]

Differential Diagnosis

Patient-reported pelvic girdle pain can be associated with signs and symptoms of inflammatory, infectious, traumatic, neoplastic, degenerative, or metabolic disorders.[26] Therefore, it is important to take a detailed subjective history and refer to the appropriate medical professional as indicated. Pelvic girdle pain can be a symptom of uterine abruption or referred pain due to urinary tract infection to the lower abdomen/pelvic or sacral region.[37] A referral to a medical professional is warranted if the patient reports any of the following:[26]

- a history of trauma

- unexplained weight loss

- a history of cancer

- steroid use or drug abuse

- human immunodeficiency virus or immunosuppressed state

- neurological symptoms/signs,

- a fever, and/or feeling systemically unwell

- severe pain that does not improve with rest [26]

When assessing a patient who presents with pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain the presence of pelvic floor muscle, hip, and lumbar spine dysfunction should be ruled out.[26] Differential diagnoses can include;

Hip dysfunction

- possible femoral neck stress fracture due to transient osteoporosis[38] [39][40]

- bursitis/tendonitis, chondral damage/loose bodies, capsular laxity, femoral acetabular impingement, labral irritations/tears, muscle strains

- referred pain from L2,3 radiculopathy[41]

- osteonecrosis of the femoral head[41]

- Paget’s disease[41]

- rheumatoid, and psoriatic and septic arthritis[41]

Lumbar spine dysfunctions and [26]

Bowel/bladder dysfunction[26]

- cauda equina syndrome

- large lumbar disc, or

- other space-occupying lesions around the spinal cord or nerve roots

Physical Therapy Management

There appears to be theoretical evidence in the research literature to support activity modification and participation in the treatment of pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain.[26] There is conflicting evidence for the use of support belts, and exercise and the current evidence to support manual therapy is weak.[26] However, clinical experience, knowledge and reasoning should be applied when implementing a treatment plan to address pain, discomfort and dysfunction related to pelvic girdle pain.

Individualized exercise programs

The [42][32] If pelvic floor dysfunction is suspected, referral to a pelvic health physiotherapist is warranted. Aquatic exercises may provide a pain-free environment for women to exercise in during pregnancy.[43]

Manual therapy

Manual therapy (i.e., soft tissue mobilization/manipulation, myofascial release, muscle energy, and muscle-assisted range of motion) and massage therapy may provide symptomatic relief[44] and may be incorporated into treatments as required.[26]

Support belts

Some patients may find support and/or pain reduction when using support belts.[45][46] Belts can be worn to improve symptoms and encourage physical activity.

Education and activity modification

Physiotherapists should educate their patients on the [47] Encouraging pain-free physical activity and exercise while also educating the patient on the importance of rest and relaxation are essential components of the physiotherapy treatment. Patients should be educated on ergonomics, lifting positions/postures during daily activities and during tasks with the baby and potentially toddlers as well as positions for sexual intercourse.

Prognosis

Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain appears to be a self-limiting condition that typically resolves by 3 months postpartum in a majority of women.[7] However, due to the complexity of the condition, it has been recommended that a biopsychosocial approach aimed at improving the individual’s self-knowledge and self-efficacy be used in the management of pelvic girdle pain to help minimize disability.[48]

Clinical Bottom Line

Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain is a multifactoral condition that requires a biopsychosocial approach to treat. It is important to rule out any differential diagnoses when assessing patients who present with pelvic girdle pain. Current research and clinical guidelines should be used to inform and assist the physiotherapist’s treatment plan for this condition.

Resources

A recent study conducted by Dufour and colleagues[47] found that a sample of surveyed physiotherapists were unaware of the current best practices and guidelines that have been published on pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain.[47] You can access the clinical practice guidelines from Section on Women’s Health and the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association and the European guidelines in the links below.

Clinton et al. (2017). References