Clinically Relevant Anatomy

The elbow complex consists of the distal humerus and proximal ulna and radius forming the humeroulna, humeroradial, and proximal radioulnar joints. The distal humerus includes the lateral capitellum, the medial trochlea, the posterior olecranon fossa, and anterior coronoid fossa.

Mechanism of Injury / Pathological Process

Pediatric population predisposed, especially during ages when the supracondylar bone is undergoing skeletal maturation and has a thin and weak cortex.[1] Fractures are classified as either an extension- or flexion-type fracture. The majority of supracondylar humeral fractures are extension-type fractures (97-99%) resulting from a fall on outstretched hand with the elbow in full extension.[2] The forced elbow hyperextension stresses the distal humerus with the olecranon acting as a fulcrum while the anterior elbow joint capsule produces an anterior tensile load, resulting in fracture and disruption of anterior periosteum. Posterior periosteum may or may not remain intact. A small number are classified as flexion-type fractures caused by a direct blunt trauma with the elbow in a flexed position.[2]

Clinical Presentation

Typically seen in the skeletally immature pediatric population, with most occurring between the ages of 5 and 7 years old.[2] The incidence rates between boys and girls is comparable. Supracondylar fracture often present with associated forearm fractures, soft tissue damage, neurologic injury, and significant risk for developing compartment syndrome, thus examination of the entire upper extremity should be performing including:[2]

- Soft tissue edema, ecchymosis, and skin puckering

- Bleeding puncture wound (indicates open fracture)

- Vascular status classification:

- Class I – well perfused (warm and red) with radial pulse

- Class II – well perfused but radial pulse absent

- Class III – poorly perfused (cool and blue or blanched) and radial pulse absent

- Neurologic status – especially ulnar nerve

- Compartment syndrome – swelling and/or ecchymosis, anterior skin puckering, and absent pulse

Diagnostic Procedures

Radiographs should include true AP of distal humerus (not elbow) and true lateral elbow views. If signs of osseous injury (fat pad sign) present the following 2 parameters used to assess for supracondylar fracture.[2]

Anterior humeral line to capitellum orientation on lateral view

- Normal elbow – line passes through middle third

- Fracture – capitellum posterior to line

The Baumann angle (Humeral capitellar angle) on AP view

- Angle between line perpendicular to long axis of humeral shaft and lateral condyle physeal line

- Normal range – 9 to 26 degrees

- Decrease in angle – varus angulated fracture with possible medial column comminution

Modified Gartland classification of supracondylar fractures (based on lateral radiograph):[2][1]

Type I

- Nondisplaced or minimally displaced (

- No disruption of periosteum – stable fracture

- Fat pad signs may be only finding

Type II

- Displaced (>2mm) with hinged intact posterior cortex

- Anterior humeral line does not pass through middle third of capitellum on lateral radiographs

- No rotational deformity on AP radiograph

Type III

- Displaced with no meaningful cortical contact, usually sagittal plane extension and frontal/horizontal plane rotation

- Significant periosteum disrupture, soft tissue and neurovascular injuries common

- Medial column comminution and collapse with malrotation in frontal plane

Type IV

- Multidirectional instability

- Incompetent periosteal hinge circumferentially, with instability in flexion and extension

Outcome Measures

add links to outcome measures here (see Outcome Measures Database)

Management / Interventions

Closed reduction and pin fixation is the most common treatment and is the indicated initial treatment for nearly all displaced closed fractures. Criteria for successful reduction include Braumann angle >10 degrees, intact medial and lateral columns, and anterior humeral line through middle third of capitellum.[2] Kirschner wires are commonly used to hold reduced fracture and arm is immobilized (between 40-60 degrees flexion).[2] With failed closed reduction, open fractures, and limb vascular compromise open reduction is the indicated treatment method. Anterior or lateral approach may be used, while posterior approach is not recommended due to significant rates of limited motion and osteonecrosis of trochlea. In-hospital traction is no longer a commonly used treatment technique given the outcomes and minimal hospital stay with closed reduction.[2]

Type I

- Immobilization with long cast (60-90 degrees flexion) for ~3weeks

- Radiographic check at 1 and 2 weeks

Types II, III, and IV

- Operative reduction and pin fixation

Differential Diagnosis

Common complications and associated injuries:

- Vascular injury

- Compartment syndrome

- Neurologic injury

- Open or associated forearm fractures

- Medial or lateral column collapse

- Cubitus varus deformity

Physiotherapy for a supracondylar fracture

Physiotherapy treatment is vital in all patients with a supracondylar fracture to hasten healing and ensure an optimal outcome. Treatment may comprise:[3]

soft tissue massage

joint mobilization

electrotherapy (e.g. ultrasound)

taping or bracing

exercises to improve strength and flexibility

education

activity modification

a graduated return to activity plan

Exercises for a supracondylar fracture

The following exercises are commonly prescribed to patients with a supracondylar fracture following confirmation that the fracture has healed, and that the orthopaedic specialist has indicated it is safe to begin mobilization. You should discuss the suitability of these exercises with your physiotherapist prior to beginning them. Generally, they should be performed 3 times daily and only provided they do not cause or increase symptoms.

Elbow Bend to Straighten

Bend and straighten your elbow as far as possible pain free (figure 3). Aim for no more than a mild to moderate stretch. Repeat 10 times provided there is no increase in symptoms.

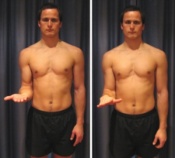

Forearm Rotations

Begin this exercise with your elbow at your side and bent to 90 degrees (figure 4). Slowly rotate your palm up and down as far as possible pain free. Aim for no more than a mild to moderate stretch. Repeat 10 times provided there is no increase in symptoms.

Tennis Ball Squeeze

Begin this exercise holding a tennis ball (figure 5). Squeeze the tennis ball as hard as possible and comfortable without pain. Hold for 5 seconds and repeat 10 times.

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)

Failed to load RSS feed from http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=1DM1CloEoPKCQyYKESwT95Q_sPot: There was a problem during the HTTP request: 422 Unprocessable Entity

References

- ↑ 1.01.1 Brubacher JW, Dodds SD. Pediatric supracondylar fractures of the distal humerus. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2008;1:190-196.

- ↑ 2.02.12.22.32.42.52.62.72.8 Omid R, Choi PD, Skaggs DL. Supracondylar humeral fractures in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2008;90:1121-32.

- ↑ http://www.physioadvisor.com.au/13642350/supracondylar-fracture-fractured-humerus-physi.htm physio advisor take control of your injury