Clinically Relevant Anatomy

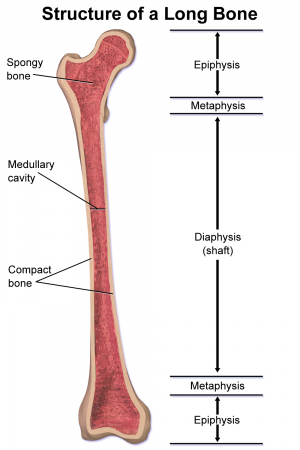

The bones of growing children contain four sections including the diaphysis (shaft), metaphysis, and epiphysis (end). The metaphysis and epiphysis are separated by the physis (growth plate). Salter Harris fractures are unique to children because they involve the growth plate. Cartilage grows from the epiphysis up toward the metaphysis and neovascularization develops from the metaphysis toward the epiphysis. Damage to the vascular supply will disrupt bone development but damage to the cartilage may not cause a problem if it is repositioned appropriately and the vasuclar supply has not been disrupted.[1]

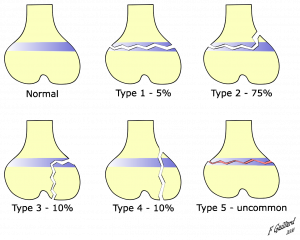

Salter-Harris fractures are classified into 5 types:

- Type I is a fracture through the growth plate.

-

Type II extends through the metaphysis and the growth plate. There is no involvement of the epiphysis. This is the most common of the Salter-Harris fractures.

- Type III is a fracture through the growth plate and the epiphysis. This is rare and when it does occur, it is usually at the distal end of the tibia.

- Type IV extends through the epiphysis, the growth plate and the metaphysis.

- Type V is a crushing type injury that affects the growth plate.[1]

There are Type VI-Type IX fractures also but these are rare.

Mechanism of Injury / Pathological Process

Salter-Harris fractures are often the result of sports related injuries however they have also been attributed to child abuse, genetics, injury from extreme cold, radiation and medications, neurological disorders, and metabolic diseases which all affect the growth plate according to the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases.[2]

Approximately 1/3rd of Salter-Harris fractures occur as the result of sports and 1/5th occur from recreational activities. They may result from a single injury or may be caused by repetitive stresses on the upper and lower extremities.[2]

Clinical Presentation

Point tenderness on palpation at the epiphyseal plate may indicate a fracture. Other signs to look for are persistent pain or pain that affects the child’s ability to tolerate weight bearing through the limb or use of the limb. [2] Soft tissue swelling and/or visible deformity could be another sign of a fracture.[2]

Diagnostic Procedures

The diagnostic process begins with obtaining a history of the patients medical status and the mechanism of injury. The Ottawa Rules and Low Risk Ankle Rule can be used to determine the need for a radiograph.[3] Radiographs may be negative, especially with a Type I fracture.[3] The contralateral limb will be radiographed as well for comparison. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT) and ultrasound may also be used. [2]

Management / Interventions

Medical Management

According to information from NIAMS, Type I and most Type II fractures are treated with cast immobilization although Type II sometimes require surgery. Both normally heal well. Type III disrupts the growth plate and therefore requires surgery. Internal fixation may be required to allow for good alignment. Type IV and Type V are also usually treated with surgery with internal fixation.[4] Type III and IV fractures with displacement of less than 2mm may also be managed non-surgically with a period of non-weightbearing in a cast followed by a period of non-weightbearing in a fracture boot.[5]

The patient is seen by their physician for assessment of their growth over the next 2 years, usually at 3-6 month intervals. Approximately 85% of growth plate fractures heal without any long term deficits. The most common complication of growth plate fractures is early arrest of bone growth which may lead to a short limb or a crooked limb. There is a greater incidence of this at the knee compared to the upper extremity.[2] In addition, Type I and II fractures have the lowest risk of physeal (growth) arrest.[5]

Rehabilitation

The patient may be referred for physical therapy to restore range of motion, strength, and function. In the acute phase after injury or surgical management, physical therapy should focus on assisting the patient with adhering to immobilization or weight bearing protocols. Controlled range of motion exercises and light strengthening can be implemented. After the growth plate has undergone sufficient healing, progressive strengthening, range of motion, balance, and proprioception exercises should be implemented. In young athletes, advanced rehabilitation should include sport-specific exercises and drills.[6]

Outcome Measures

Return to play/return to sport testing should be used. Involved muscle strength should be 90% of the contralateral muscle strength in order for athletes to return to previous sports or activities.[6] Joint- or body region-specific outcome measures can be used based on the fracture location.

Differential Diagnosis

According to Moore et al., ankle fractures, wrist, and scaphoid fractures and complications should be considered.[1]

Additionally, one needs to consider medications, radiation, neurological disorders, metabolic disease or exposure to extreme cold especially if no specific injury can be identified.[2]

References

- ↑ 1.01.11.2 Moore W, Smith TH. Salter-harris fractures. ↑ 2.02.12.22.32.42.52.6 National Institutes of Health. Growth plate injuries. ↑ 3.03.1 Su AW, Larson AN. Pediatric ankle fractures: concepts and treatment principles. Foot Ankle Clin 2015;20(4):705-719.

- ↑ Consumer Health Information Network. arthritis-symptom.com/fracture/salter-harris-fracture.htm

- ↑ 5.05.1 Wuerz TH, Gurd DP. Pediatric physeal ankle fracture. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2013; 21:234-244.

- ↑ 6.06.1 Paterno, MV. Unique issues in the rehablitation of the pediatric and adolescent athlete after musculoskeletal injury. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev 2016;24:178-183.