Introduction

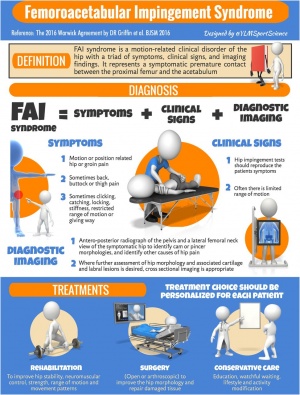

Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) syndrome is a motion-related clinical disorder of the hip involving premature contact between the acetabulum and the proximal femur and which results in particular symptoms, clinical signs and imaging findings.[1][2] Degenerative changes and osteoarthritis may develop in the long-term as a result of this abnormal contact.[3]

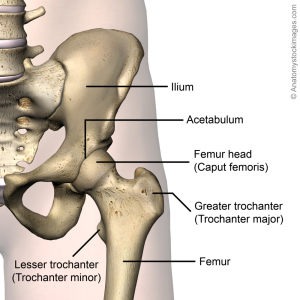

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

The hip (acetabulofemoral joint) is a synovial joint formed between the femur and acetabulum of the pelvis. The head of the femur is covered by Type II collagen (hyaline cartilage) and proteoglycan. The acetabulum is the concave portion of the ball and socket joint. The acetabulum has a ring of fibrocartilage called the labrum that deepens the acetabulum and improves stability of the hip joint. For a more detailed review of the anatomy of the hip, please see the Hip Anatomy article.

Mechanism of Injury / Pathological Process

FAI syndrome is associated with certain variations in the morphology of the hip joint. Cam morphology describes a flattening or convexity of the femoral head neck junction.[2] This morphology is more common in men.[3][5]

Pincer morphology describes “overcoverage” of the femoral head by the acetabulum in which the acetabular rim is extended beyond the typical amount, either in one focal area or more generally across the acetabular rim.[2] This morphology is more common in women.[3][5]

An estimated 85% of patients with FAI have mixed morphology, meaning both cam and pincer morphologies are present,[3] although Raveendran et al (2018) found only 2% of subjects in their prospective longitudinal cohort study had mixed morphology (albeit in a primarily middle-aged population).[5]

It is important to note that these morphologies are thought to be fairly common (around 30% of the general population),[8] including in people without hip symptoms. Raveendran et al (2018) found that 25% of men and 10% of women had evidence of cam morphology in at least one hip while 6-7% of men and 10% of women demonstrated pincer morphology in their longitudinal cohort study.[5] Thus the isolated presence of either cam or pincer morphology is insufficient for a diagnosis of FAI syndrome.[2]

Both types of morphology can lead to damage to the articular cartilage and the labrum due to impingement between the acetabular rim and the femoral head during movement, hence causing the symptoms of FAI syndrome.[9] Metabolic analysis of tissue samples by Chinzei et al (2016) suggested that articular cartilage may be the main site of inflammation and degeneration in hips with FAI and that if OA progresses, metabolic activity spreads to the labrum and synovium and labrum.[9]

Given that cam and pincer morphologies can be present in asymptomatic individuals, Casartelli et al (2016) propose that other factors outwith the bony structures may be involved with FAI syndrome.[10] Weakness of deep hip muscles could not only compromise hip stability but also lead to overload of secondary movers of the hip, thus causing an anterior glide of the femoral head into the acetabulum and increased joint loading.[10] Repeated loading of the labrum in this may could lead to upregulation of nociceptive receptors in that structure through the production of neurotransmitters such as substance P.[10]

Etiology

Based on a systematic review performed by Chaudhry and Ayeni (2014), the etiology of FAI syndrome is likely multifactorial.[3] Further research is required to better understand development of the FAI-associated morphologies but the following factors may be associated with its development;[3]

- Intrinsic factors, given 1) radiological findings of FAI-associated morphologies among subjects those with affected siblings and 2) higher instances of cam morphology in men and pincer morphology in women

- Exposure to repetitive and often supraphysiologic hip rotation and hip flexion during development in childhood and adolescence (e.g. hockey, basketball or football). Repeated stress of this type may trigger adaptive remodeling and eventually development of FAI-associated morphologies and symptoms

- History of childhood hip disease (e.g. slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) or Legge-Calve-Perthes disease) which may have altered the shape of the femoral head

- Malunion following femoral neck fractures which may have altered the contour of the femoral head/neck

- Surgical over-correction of conditions such as hip dysplasia may lead to the pincer morphology

Clinical Presentation

Patients with suspected FAI syndrome typically report stiffness and pain in the hip and/or groin. Heterogeneity of diagnostic criteria in past research has meant that it has been difficult to ascertain the full scope of physical impairments stemming from FAI.[11] However, pain from FAI is commonly held to be aggravated with acceleration sports as well as squatting, climbing stairs and prolonged sitting.[12] With FAI that may have advanced to hip osteoarthritis, signs and symptoms more typical of this condition may be identified.

In the Warwick Agreement on FAI syndrome published in 2016, the authors noted that a particular triad of symptoms, clinical findings and imaging findings are required for a diagnosis of FAI.[2]

Symptoms

- The primary symptom reported with this condition is hip or groin pain related to certain movements or positions[2]

- Pain may also be reported in the thigh, back or buttock[2][13]

- Additional symptoms such as stiffness, restricted ROM, clicking, catching, locking or giving way may be reported[2][13]

Clinical Findings

- As per the Warwick Agreement from 2016, there is no single clinical sign that will indicate a diagnosis of FAI.[2] Indeed, as per the presentation by Adam Smithson provided below in the Presentations section, issues with low specificity of tests such as the impingement test (FADIR) limit their accuracy and hence usage as stand-alone tests.[14] Otherwise, there is a risk of false positives, inaccurate diagnosis of FAI syndrome and incorrect treatment.[14] Smithson suggests that a cluster of tests could be studied to develop a clinical prediction rule to achieve both high specificity and sensitivity and thus more accurate diagnosis in a clinical setting.[14]

- Various pain-provocation hip impingement tests are used clinically but flexion adduction internal rotation (FADIR) is the most commonly used test and is sensitive but not specific.[2][15] The FADIR position of provocation is associated with impingement at the anterior rim of the acetabulum.[13] Pain associated with the posterior rim can be provoked by passively bringing the hip from flexion to extension while maintaining a position of hip abduction and external rotation with the leg hanging off the examination table.[13]

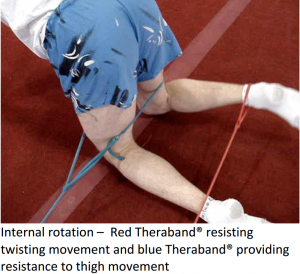

- Hip ROM is often restricted, most commonly internal rotation with the hip flexed.[2] However, Diamond et al (2015) noted that in some studies, controls were not imaged for asymptomatic FAI thus caution is needed with generalizing these results and further research will help clarify the impact of FAI on hip ROM.[11]

- Frangiamore et al (2017) recommended assessing the single limb squat to identify hip abductor weakness as well as reproduction of pain with hip flexion (which could be FAI or other intra-articular pathology).[13] Similarly, they recommended assessing stair ascending and descending since this this requires greater hip flexion than walking on a flat surface.[13]

- Findings of strength deficits associated with FAI have been reported in the literature (particularly hip flexion and adduction) but as with studies investigating ROM and FAI, some controls were not imaged for asymptomatic FAI thus caution is needed with generalizing these results.[11] Further research will help clarify the impact of FAI on strength, particularly at functional as opposed to maximal levels of muscle contraction.[11]

Frangiamore et al (2017) provided a video of an overview of their recommended hip examination. It is a supplement near the end of their open access article which can be access by clicking on on the image below.

Imaging Findings

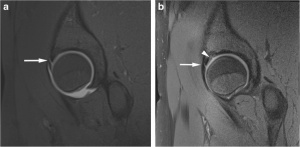

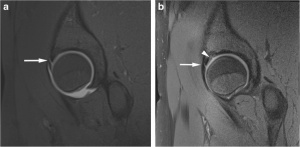

- AP x-rays of the pelvis and lateral x-rays of the femoral neck are recommended initially for suspected FAI syndrome. These views can provide general information relating to the hips as well as specific information related to cam or pincer morphologies or other potential sources of the patient’s pain.[2]

- If further assessment is required (e.g. for better appreciation of 3D morphology of the hip or for associated cartilage and labral lesions), cross-sectional imaging (CT or MR arthrogram*) is recommended$.[2]

- *MR arthrogram has typically been preferred over MRI because it has shown greater accuracy in identifying defects in the labrum and cartilage.[16] However, more recent research suggests that 3T MRI is at least equivalent to 1.5T MRA for detecting these types of defects.[16]

- $The role of advanced imaging for the diagnosis of FAI syndrome is actually somewhat controversial. Reiman et al (2017) report that in the studies included in their systematic review, patients had such high pre-test probabilities of FAI that advanced imaging would do little to improve on the probability of that diagnosis.[17] Having said that, these studies were conducted on patients attending orthopaedic surgical clinics, thus limiting generalizability of the findings to the general population.[17] As well, issues with heterogeneity in diagnostic criteria used in different studies were once again identified.[17] Cunningham et al (2017) found that advanced imaging (MRA or MRI) was never a cost-effective adjunct to a thorough history and physical examination for diagnosing FAI.[18] Supplementing history and physical examination with diagnostic injection may be of valuable for general practitioners but is of equivocal benefit for specialists with higher prevalence of FAI in their patient populations and with more sensitive physical examination skills.[17]

A method of assessing contact pressure within the hip during flexion has been proposed and tested for cam morphologies.[19] Because this measurement is done using a fibre-optic transducer during arthroscopic surgery, thus the diagnosis of FAI will already have been made before that point.[19] However, Kaya (2017) suggests that this intra-articular measurement will be helpful for;[19]

- providing a more detailed assessment of cam morphologies and associated pathophysiology

- establishing an intraoperative index for the proper area and depth of corrective trimming of bone

A video of this arthroscopic procedure can be viewed near the end of Kaya’s open access article Differential Diagnosis

Acute hip pain due to tumour, infection, septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, fracture and avascular necrosis are red flag conditions that should be ruled out.[20] In athletes, other causes of hip pain include inguinal pathology, adductor pathology and athletic pubalgia.[13]

Outcome Measures

international Hip Outcome Tool (iHOT)

Hip and Groin Outcome Score (HAGOS)

Hip Outcome Score (HOS)

Harris Hip Score (HHS) [21]

Non-arthritic Hip Score [21]

Management / Interventions

Researchers are still trying to ascertain the best approach to managing this condition. To date, hip arthroscopy has commonly been utilized but early reports tended to be limited to cohort-level, typically showed only short-term benefits and were usually authored by surgeons, thus introducing the possibility of population bias.[5][15][22][23] In addition, Peters et al (2017) stated that they found heterogeneity in the surgical criteria reported in the literature leading them to question whether the same condition was in fact being treated in all studies.[24] They found that only 56% of the reviewed studies included at least one surgical criterion from each of the three categories recommended in the Warwick Agreement.[24] As well, the vast majority of the studies (92%) included diagnostic imaging as a criterion, yet there is currently no consensus on specific imaging modalities or cut-off values to determine when surgery is indicated.[24] Failed conservative treatment was found to be an infrequent surgical criterion in this review.[24] The issue of heterogeneity of diagnostic and surgical criteria in the research has been raised by multiple authors.[11][15][17] Reiman and Thorburg (2015) likened the rapid increase in surgical correction for FAI to the rise in shoulder arthroscopies between 2000 and 2010 which was not based on quality evidence. They summarized the state of research on FAI as follows: “clinical impressions of improvement from treatment often appear favourable, but these impressions can be deceiving when valid outcome measures, spontaneous recovery and/or placebo effects are not accounted for.”[15]

Thus, these various issues should be considered when trying to determine the best course of action for a patient with FAI syndrome. As per the Warwick Agreement on FAI syndrome (2016), the authors stated that “[t]here is currently no high-level evidence to support the choice of a definitive treatment for FAI syndrome” therefore all options should be considered for each patient and an approach should be selected based on a shared decision-making process.[2] In the meantime, high quality research should be conducted to clarify the effectiveness of surgical versus on-surgical treatment of FAI and also to determine if corrective surgery can prevent OA as is proposed.[15]

Surgical Management

Arthroscopy is the most common surgical procedure for FAI discussed in the literature. The exact nature of each surgery vary according to the treating surgeon’s clinical judgement based on preoperative testing and intraoperative findings but will typically involve acetabuloplasty (trimming and reshaping the acetabular rim), labral repair/debridement and/or femoroplasty (reshaping the femoral head-neck junction).[23]

Based on a systematic review performed by Diamond et al (2015), hip arthroscopy for FAI appears to improve ROM in the sagittal plane but not the frontal plane during gait.[11] In addition, limitations in hip ROM during stair climbing did not improve following surgical correction of morphological findings, leading the authors to suggest that hip function in the sagittal and transverse planes may not resolve spontaneously following surgery and that patients may require post-operative training in order to regain normal functional range of motion.[11]

adhesions, DVTs and CRPS.[15] Rates of surgical complications reported in the literature are variable.[13] In a systematic review published in 2017, a complication rate of 3.3% was calculated from hip arthroscopies reported in English literature.[25] Potential complications from surgical management include the following;

- Neuropraxia[25]

- Chrondral injury[25]

- Labral injury[25]

- Heterotopic ossification[25]

- Compression injuries e.g. pudendal nerve, scrotum, labia major[25]

- Injury to the femoral head[25]

- Adhesion[15][25]

- Infection[25]

- DVT[15][25]

- CRPS[15][25]

- Perineal skin damage[25]

- Vascular injury (haematoma)[25]

- Muscle pain[25]

- Incomplete reshaping[25]

- Femoral neck fracture[25]

- Hip instability[25]

- Iliopsoas tendinitis[25]

- Avascular necrosis of femoral head[25]

- Ankle pain[25]

- Bursitis[25]

Surgical complications are a recommended area of future research to help inform the clinical decision-making process.[15]

Surgery with Post-Operative Physiotherapy Programme

The addition of a physiotherapist-prescribed rehabilitation program following arthroscopy was found to improve primary outcomes (International Hip Outcome Tool and sport subscale of the Hip Outcome Scale) to a clinically-relevant degree at 14 weeks post-surgery compared to a control group who followed a self-management program with general guidance from their surgeon.[22] In the same study, the results at 24 weeks were inconclusive due to the small sample size.[22] Physical outcomes were not evaluated in this study.

Subjects in the physiotherapy treatment group attended one pre-operative and six post-operative 30-minute sessions with a physiotherapist.[22] The post-op visits were two weeks apart on average, ending at 12 weeks. Treatment during these sessions consisted of education, manual therapy (mandatory release of key trigger points, optional lumbar mobilisation) and, starting at 6-8 weeks post-surgery, functional and sport-specific drills.[22] Training within the patient’s normal sport environment started at 10-12 weeks post-surgery.[22] In addition, these patients performed a daily home exercise program (see exercise sheet below) and an unsupervised gym and aquatic programme (pool walking, stationary bike, cross-trainer and eventually swimming and lower body resistance) at least twice per week.[22]

The full treatment protocol can be viewed Conservative Management

Casertelli et al (2016) suggest that improving neuromuscular function of the hip should be a goal of conservative protocols for FAI syndrome due to weakness of deep hip musculature and an expected subsequent reduction in dynamic stability of the hip joint.[10] These authors recommend including hip-specific and functional lower limb strengthening, core stability and postural balance exercises.[10] To improve dynamic stability of the hip, there should be a focus on strengthening the deep hip external rotators, abductors and flexors in the transverse, frontal and sagittal planes.[10] With this approach, the authors propose that for at least some patients with symptomatic FAI, loading of the labrum could be reduced which would then facilitate downregulation of nociceptive neurotransmitters in the labrum.[10] As well, strengthening could help with more generalized inflammation in the hip joint that is commong with FAI syndrome.[10] In a randomized controlled trial, Mansell et al (2018) compared patient outcomes for surgical intervention versus physiotherapy.[26] The group of subjects was 58.8% male with a mean age of 30.1 years.[26] Eligible subjects had to have a diagnosis of FAI and/or labral tear and also report pain in the anterior hip or groin, have pain with the FADIR test (passive flexion, adduction, internal rotation), have pain reproduced with passive or active flexion and experience pain relief with an intra-articular injection. Outcomes were the Hip Outcome Score (including daily activity and sport subscales), International Hip Outcome Tool, Global Rating of Change and return to work. The surgical procedure included a possible combination of labral repair or debridement, trimming of the acetabular rim and/or femoroplasty, as determined by the surgeon. The physiotherapy protocol was tailored to each subject based on a standardized assessment conducted by a physiotherapist. The program could consist of manual therapy, motor control exercises and mobility/stretching exercises as follows;[23]Mansell et al 2018

| Manual Therapy | Motor Control Exercises | Mobility Exercises |

|---|---|---|

| Hip Extension in Standing Mobilisation with Movement (MWM) | Reverse Lunge with Front Ball Tap | Kneeling Internal Rotation Self-Mobilization with Lateral Distraction |

| Hip Distraction during Internal Rotation MWM | Isolateral Romanian Deadlift with Dowel | Half-Kneel FABER Self-Mobilization |

| Loaded Lateral Hip Distraction MWM | Lateral Step-Down with Heel Hover | Quadruped Rock Self-Mobilization with Lateral Distraction |

| Loaded Internal Rotation | Side Plank | Prone Figure-4 Self-Mobilization |

| Lateral Glide in External Rotation | Seated Isometric Hip Flexion | ITB Soft Tissue Self-Mobilization on Foam Roll |

| Long Axis Hip Distraction | Supine Hip Flexion with Theraband | Quadriceps Soft Tissue Self-Mobilization on Foam Roll |

| x | x | Piriformis/Glut Min Self Myofascial Release on Ball |

| x | x | Standing Figure-4 Stretch |

| x | x | Kneeling Tri-Planar Mobilizations |

Please note that the above program has been described in detail in the authors’ supplemental files which can be viewed [23] They also suggested further investigation of the optimal timing, dosing and choice of exercise within a program. Finally, the authors noted that patient expectations must be considered and that if they are unwilling to try conservative options, education may be required regarding the fact that;[23]

- There are natural differences in hip morphology and not all morphologies are abnormal or pathological

- There is a high rate of conversion to total hip arthroplasty within two years of arthroscopic surgery of the hip

- Joint degeneration in a given patient may not progress beyond what is typical in a morphologically normal hip i.e. cam or pincer morphology does not automatically lead to a greater prevalence of degeneration compared to hips without these morphologies

Personalised Hip Therapy – The UK FASHIoN Trial

In preparation for an RCT comparing hip arthroscopy with ‘best conservative care,’ Wall et al (2016) developed a conservative care protocol based on a systematic review of the literature and a Delphi study group.[8] Based on a pilot study conducted by the same group, the authors stated that they felt that Personalised Hip Therapy is “safe and deliverable in the ‘real world’ of the NHS” (National Health Service in the UK). The full FASHIoN RCT is currently underway and thus no results are available yet.[27]

The Personalised Hip Therapy protocol is designed to last for 12 weeks with a minimum of three face-to-face and three phone/email contacts with the treating physiotherapist. A maximum of 10 contacts with the physiotherapist were permitted for the purposes of the FASHIoN trial. The full protocol is as follows;[8]

| Core Component | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 Patient Education and Advice | Relative rest and lifestyle/ADL/sport modifications to try to avoid FAI e.g. avoidance of hip deep flexion, adduction and internal rotation |

| 2 Patient Assessment | Thorough patient history, pain-free PROM of hip, hip impingement testing and strength of hip flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, internal rotation and external rotation |

| 3 Help with Pain Relief | Anti-inflammatories for 2-4 weeks or simple analgesics if anti-inflammatories don’t help, adherence to personalised exercise programme |

| 4 Exercise-Based Hip Programme | Start with muscle control work (pelvis, hip, glutes, abdominals), progressing to non-vigorous stretching (hip external rotation, hip abduction in flexion and extension) and strengthening (glut max, short external rotators, glut med, abdominals, lower limb in general) |

| Optional Components[8] | Description |

|---|---|

| Manual therapy | Hip joint mobilisations (e.g. distraction, AP glides) and trigger point work |

| Hip joint injection | For patients who do no improve with core treatment components above. For purposes of the FASHIoN trial, a maximum of one steroid injection could be included |

| Orthotics | Custom orthotics as an alternative to treatment of biomechanical abnormalities by physiotherapist |

| Taping | To assist with postural modification e.g. tape thigh into external rotation and abduction |

| Group-based treatments | For the purposes of the FASHIoN trial, group treatments could be included but only in addition to the core components |

| Treatment of additional pathology/symptoms | Based on the findings of the treating physiotherapist, pathology/symptoms that were felt to be affecting the FAI could also be treated |

For the purposes of the FASHIoN trial, hydrotherapy, acupuncture, electrotherapy and forceful manual techniques were excluded from the protocol.[8]

Bracing

Newcomb et al (2018) investigated the immediate and longer term effects of wearing a brace (a Don Joy S.E.R.F./Stability through External Rotation of the Femur model). They found that the brace did modify the kinematics of patients with FAI by limiting movements that were associated with hip impingement (flexion, internal rotation and adduction of the hip) during common activities (squat, stair climbing and stair descending). The single limb squat was also studied but the brace did not change the kinematics involved with this task. The kinematic changes that were identified did not, however, lead to decreased pain or improvement in patient-reported outcomes either immediately or after four weeks of daily brace use. The authors’ conclusion was that there may be a sub-group of patients with FAI syndrome that may benefit from bracing but based on their particular study, the use of bracing is not supported as a general conservative therapy for this condition.

Prognosis

Patients treated for symptomatic FAI syndrome frequently report improvement in their symptoms and are able to return to their usual activities.[2] However, the long-term prognosis is not known, nor is it known if treatment of FAI syndrome prevents the development of hip OA.[2] According to the authors in the Warwick Agreement, symptoms of FAI syndrome will probably worsen if no treatment is provided.[2]

Resources

Presentations

References

- ↑ Murphy NJ, Eyles J, Bennell KL, Bohensky M, Burns A, Callaghan FM et al. Protocol for a multi-centre randomised controlled trial comparing arthroscopic hip surgery to physiotherapy-led care for femoroacetabular impingement (FAI): the Australian FASHIoN trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017 Sep 26;18(1):406.

- ↑ 2.002.012.022.032.042.052.062.072.082.092.102.112.122.132.142.152.16 Griffin DR, Dickenson EJ, O’Donnell J, Agricola R, Awan T, Beck M et al. The Warwick Agreement on femoroacetabular impingement syndrome (FAI syndrome): an international consensus statement. Br J Sports Med. 2016; 50(19):1169-76.

- ↑ 3.03.13.23.33.43.5 Chaudhry H, Ayeni OR. The etiology of femoroacetabular impingement: what we know and what we don’t. Sports Health. 2014 Mar;6(2):157-61.

- ↑ The Young Orthopod. Femoroacetabular Impingement (FAI). Available from: ↑ 5.05.15.25.35.4 Raveendran R, Stiller JL, Alvarez C, Renner JB, Schwartz TA, Arden NK et al. Population-based prevalence of multiple radiographically-defined hip morphologies: the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2018 Jan;26(1):54-61.

- ↑ RegencyMarketing. Cam impingement. Available from: ↑ RegencyMarketing. Pincer impingement. Available from: ↑ 8.08.18.28.38.4 Wall PD, Dickenson EJ, Robinson D, Hughes I, Realpe A, Hobson R, Griffin DR, Foster NE. Personalised Hip Therapy: development of a non-operative protocol to treat femoroacetabular impingement syndrome in the FASHIoN randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(19):1217-23.

- ↑ 9.09.1 Chinzei N, Hashimoto S, Fujishiro T, Hayashi S, Kanzaki N, Uchida S et al. Inflammation and Degeneration in Cartilage Samples from Patients with Femoroacetabular Impingement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016 Jan 20;98(2):135-41.

- ↑ 10.010.110.210.310.410.510.610.7 Casartelli NC, Maffiuletti NA, Bizzini M, Kelly BT, Naal FD, Leunig M. The management of symptomatic femoroacetabular impingement: what is the rationale for non-surgical treatment? Br J Sports Med. 2016 May;50(9):511-2.

- ↑ 11.011.111.211.311.411.511.6 Diamond LE, Dobson FL, Bennell KL, Wrigley TV, Hodges PW, Hinman RS. Physical impairments and activity limitations in people with femoroacetabular impingement: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2015 Feb;49(4):230-42.

- ↑ Newcomb NRA, Wrigley TV, Hinman RS, Kasza J, Spiers L, O’Donnell J, Bennell KL. Effects of a hip brace on biomechanics and pain in people with femoroacetabular impingement. J Sci Med Sport. 2018 Feb;21(2):111-116.

- ↑ 13.013.113.213.313.413.513.613.7 Frangiamore S, Mannava S, Geeslin AG, Chahla J, Cinque ME, Philippon MJ. Comprehensive Clinical Evaluation of Femoroacetabular Impingement: Part 1, Physical Examination. Arthrosc Tech. 2017 Oct 30;6(5):e1993-e2001.

- ↑ 14.014.114.214.3 Adam Smithson. Femoral Acetabular Impingement by Adam Smithson, University of Nottingham. Available from: ↑ 15.015.115.215.315.415.515.615.715.815.9 Reiman MP, Thorborg K. Femoroacetabular impingement surgery: are we moving too fast and too far beyond the evidence? Br J Sports Med. 2015 Jun;49(12):782-4.

- ↑ 16.016.116.2 Chopra A, Grainger AJ, Dube B, Evans R, Hodgson R, Conroy J et al. Comparative reliability and diagnostic performance of conventional 3T magnetic resonance imaging and 1.5T magnetic resonance arthrography for the evaluation of internal derangement of the hip. Eur Radiol. 2018 Mar;28(3):963-971.

- ↑ 17.017.117.217.317.4 Reiman MP, Thorborg K, Goode AP, Cook CE, Weir A, Hölmich P. Diagnostic Accuracy of Imaging Modalities and Injection Techniques for the Diagnosis of Femoroacetabular Impingement/Labral Tear: A Systematic Review With Meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2017 Sep;45(11):2665-2677.

- ↑ Cunningham DJ, Paranjape CS, Harris JD, Nho SJ, Olson SA, Mather RC 3rd. Advanced Imaging Adds Little Value in the Diagnosis of Femoroacetabular Impingement Syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017 Dec 20;99(24):e133.

- ↑ 19.019.119.2 Kaya M. Measurement of Hip Contact Pressure During Arthroscopic Femoroacetabular Impingement Surgery. Arthrosc Tech. 2017 May 1;6(3):e525-e527.

- ↑ Martin RL, Enseki KR, Draovitch P, Trapuzzano T, Philippon MJ. Acetabular labral tears of the hip: Examination and diagnostic challenges. JOSPT. 2006;36(7):503-15.

- ↑ 21.021.1 Emara K, Samir W, Hausain Motasem EH, Abd El Ghafar K. Conservative treatment for mild femoroacetabular impingement. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery. 2011;19(1):41-5.

- ↑ 22.022.122.222.322.422.522.6 Bennell KL, Spiers L, Takla A, O’Donnell J, Kasza J, Hunter DJ, Hinman RS. Efficacy of adding a physiotherapy rehabilitation programme to arthroscopic management of femoroacetabular impingement syndrome: a randomised controlled trial (FAIR). BMJ Open. 2017 Jun 23;7(6):e014658.

- ↑ 23.023.123.223.323.4 Mansell NS, Rhon DI, Marchant BG, Slevin JM, Meyer JL. Two-year outcomes after arthroscopic surgery compared to physical therapy for femoracetabular impingement: A protocol for a randomized clinical trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016 Feb 4;17:60.

- ↑ 24.024.124.224.3 Peters S, Laing A, Emerson C, Mutchler K, Joyce T, Thorborg K, Hölmich P, Reiman M. Surgical criteria for femoroacetabular impingement syndrome: a scoping review. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(22):1605-1610.

- ↑ 25.0025.0125.0225.0325.0425.0525.0625.0725.0825.0925.1025.1125.1225.1325.1425.1525.1625.1725.1825.1925.20 Nakano N, Lisenda L, Jones TL, Loveday DT, Khanduja V. Complications following arthroscopic surgery of the hip: a systematic review of 36 761 cases. Bone Joint J. 2017 Dec;99-B(12):1577-1583.

- ↑ 26.026.1 Mansell NS, Rhon DI, Meyer J, Slevin JM, Marchant BG. Arthroscopic Surgery or Physical Therapy for Patients With Femoroacetabular Impingement Syndrome: A Randomized Controlled Trial With 2-Year Follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2018 Feb 1:363546517751912. doi: 10.1177/0363546517751912. [Epub ahead of print]

- ↑ ↑ Physiotutors. Pelvic Control Exercises | Femoroacetabular Impingement (FAI). Available from: ↑ Physiotutors. Mobility Exercises | Femoroacetabular Impingement (FAI). Available from: ↑ Physiotutors. Strengthening Exercises | Femoroacetabular Impingement (FAI). Available from: