Introduction

The information on this page has developed for you from the expert work of

Cerebral Palsy (CP) is a disorder of movement and posture that appears during infancy or early childhood resulting from damage to the brain. The damage to the brain is permanent and cannot be cured but the earlier we start with intervention the more improvement can be made.Any non-progressive central nervous system (CNS) injury occurring during the first 2 (some say 5) years of life is considered to be CP. There are several definitions of Cerebral Palsy within the literature, although these may all vary slightly in the way they are worded they are all similar and can be summarised to:

Cerebral Palsy is a group of permanent, but not unchanging, disorders of movement and/or posture and of motor function, which are due to a non-progressive interference, lesion, or abnormality of the developing/immature brain[1].

This definition specifically excludes progressive disorders of motor function, defined as loss of previously acquired skills in the first 5 years of life.

We only talk about cerebral palsy if the brain damage arises during one of the following periods:

After the age of 5 we speak of stroke or traumatic brain injury.

Unfortunately, it is difficult to access and clarify the prevalence and incidence rate of disabilities in poor-resource settings (Gladstone, 2010). Not only the prevalence of childhood disability is on the rise and Cerebral Palsy is one of the costliest chronic conditions, but also life expectancies are improving, which increases the burden of Cerebral Palsy (Papavasiliou, 2009). For comparison, in the USA, there are approximately 700’000 children with Cerebral Palsy, 2-5/ 1000 born.

Cerebral Palsy is the most common motor disability in childhood. The aetiology of Cerebral Palsy is very diverse and multifactorial. The causes are congenital, genetic, inflammatory, infectious, anoxic, traumatic and metabolic. The injury to the developing brain may be prenatal, natal or postnatal. As much as 75%-80% of the cases are due to prenatal injury with less than 10% being due to significant birth trauma or asphyxia. The most important risk factor seems to be prematurity and low birth weight with risk of Cerebral Palsy increasing with decreasing gestational age and birth weight.

Population-based studies from around the world report prevalence estimates of Cerebral Palsy ranging from 1.5 to more than 4 per 1,000 live births or children of a defined age range. Recent advances in neonatal management and obstetric care have not shown a decline in the incidence of Cerebral Palsy. With a decline in infant mortality rate, there has actually been an increase in the incidence and severity of Cerebral Palsy. The incidence in premature babies is much higher than in term babies. Cerebral Palsy is more common among boys than among girls and more common among black children than among white children. Most of the children identified with Cerebral Palsy have Spastic Cerebral Palsy (77, 4%). Over half of the children identified with Cerebral Palsy (58, 2%) can walk independently, 11, 3% walks using a handheld mobility device and 30, 6% has limited or no walking ability. Many children with Cerebral Palsy also do have at least one co-occurring condition (e.g. 41% Epilepsy). The incidence of Cerebral Palsy has not declined despite the improved perinatal and obstetric care. Even at centres where optimal conditions exist for perinatal care and birth asphyxia is relatively uncommon, the incidence of Cerebral Palsy in term babies has remained the same.

The overall prevalence worldwide has increased during the last decades because of increased survival rates. Here are some facts on the epidemiology of Cerebral Palsy:

Improved medical care has decreased the incidence of Cerebral Palsy among some children. Medical advances have also resulted in the survival of children who previously would have died at a young age.

The type of cerebral palsy has also changed:

There are different risk factors for each stage at which a child might develop Cerebral Palsy. These can be broken down into Prenatal, Perinatal and Postnatal.

Prenatal:

Perinatal:

Postnatal (0-2 years):

There is no way to predict which child’s brain will be damaged by one of these factors or to what the extent of the damage will be. None of these factors always results in brain damage and even when brain damage occurs, the damage does not always result in Cerebral Palsy.

For example: Some children may have an isolated hearing loss from their meningitis, others will have severe intellectual disability and some will have Cerebral Palsy. The practice of classification categorizes those presentations together with similar characteristics and distinguishes those cases with diverse features apart or separate. The benefit of using a classification system for children with Cerebral Palsy is that it provides a common language to quickly convey a clinical snap shot of a child’s presentation. There have been many attempts to develop a reliable, repeatable and valid classification system for children with Cerebral Palsy. However, few have been successful owing to the heterogeneous nature of Cerebral Palsy that makes classification a complex process. As far back as 1862, orthopaedic surgeon William Little first grouped the clinical presentations of 47 cases as either:

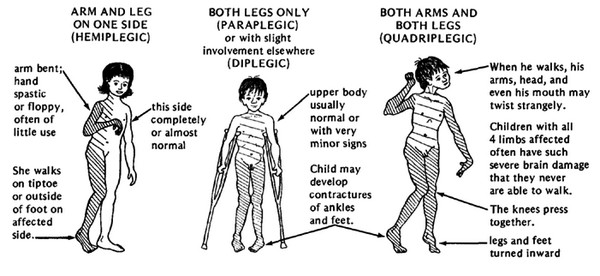

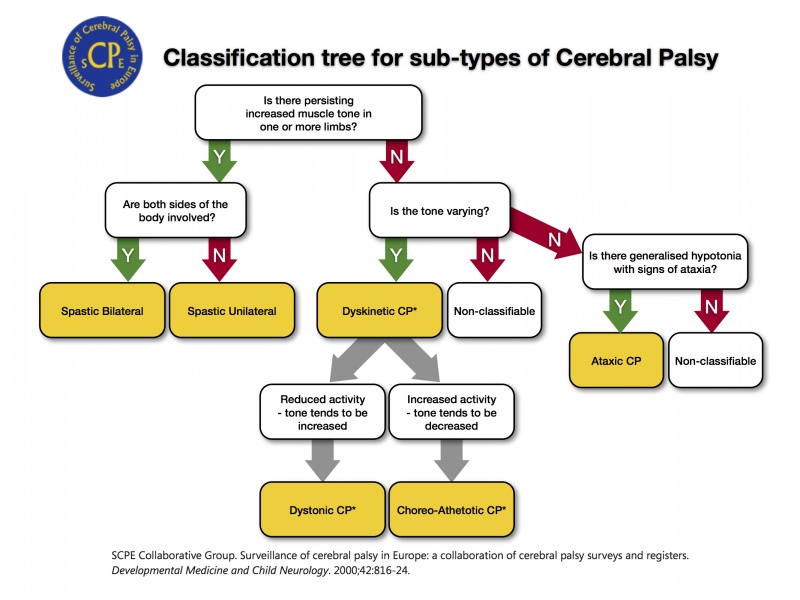

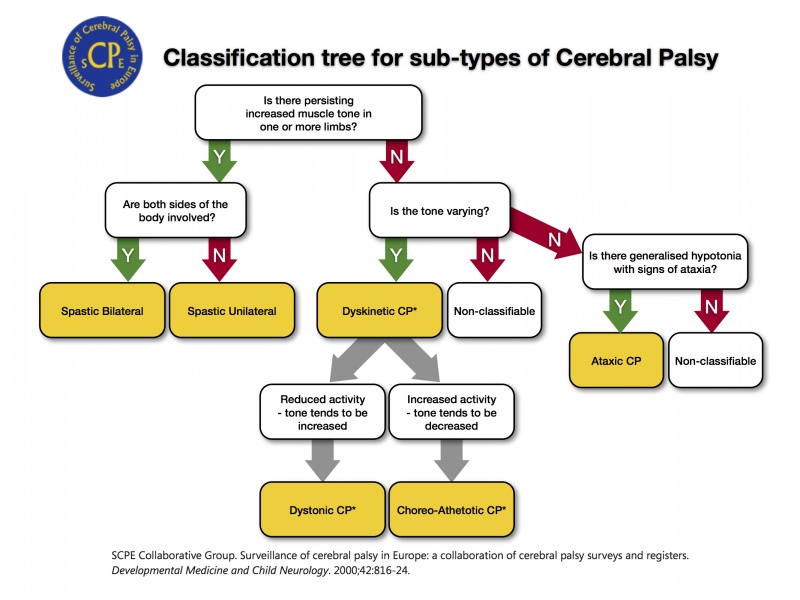

Research and development of classification systems for children with Cerebral Palsy have focused on the aetiology, brain imaging, subtype and topographical distribution of the predominant movement disorder, gait and gross motor function. [3] The Swedish Classification (SC) of Cerebral Palsy subtypes employs a topographical descriptive method. [4] It describes the type of muscle tone (spastic, dyskinetic, ataxic or mixed) and the number and distribution of the affected limbs (monoplegia, hemiplegia, diplegia, tetraplegia, and quadriplegia). [4] [5] The Surveillance of Cerebral Palsy in Europe (SCPE) developed this concept further and proposed a new classification of Cerebral Palsy subtypes in the year 2000. [6] (FIGURE 1) The SCPE classification system provides a decision flow chart to aid classification into neurological and topographical categories, with clearly defined symptoms and requirements provided for each neurological category. [2] In contrast to the SC, the SCPE system separates Spastic Cerebral Palsy into upper or lower limb divisions, with either bilateral or unilateral involvement. The SC and SCPE classifications of Cerebral Palsy sub-type require the clinician to identify the predominant motor disorder. [7] There is some concern relating to the validity and reliability of the SC and SCPE tools, with only a moderate level of agreement achieved for the intra-observer reliability of Cerebral Palsy subtypes. [8] The differences arise when clinical opinion is divided over which motor pattern is predominant. However While the SC and SCPE tools may help describe a child’s presentation, they do not define any criteria for recording the functional abilities of the child. Identifying, describing and classifying a child’s functional abilities can also increase the reliability of diagnosing children with Cerebral Palsy. Further research has focused on developing gait and functional classification systems for ambulatory children with Cerebral Palsy. Many children with Cerebral Palsy have a mixed form of Cerebral Palsy. Here the definition and classification used as agreed in Europe. More information on definitions, outcome of some studies, exchange of information on clinical practice on Cerebral Palsy in Europe you can find, after registering Anatomical classification are as follows:

Spastic Cerebral Palsy: are used to distinguish between quadriplegia, diplegia and hemiplegia. Spastic Cerebral Palsy is either bilateral or unilateral. Dyskinetic Cerebral Palsy and Ataxic Cerebral Palsy: always involve the whole body (bilateral). Spasticity is defined as an increase in the physiological resistance of muscle to passive motion. It is part of the upper motor neuron syndrome characterized by hyperreflexia, clonus, extensor plantar responses and primitive reflexes. Spastic Cerebral Palsy is the most common form of Cerebral Palsy. Approximately 80% to 90% of children with Cerebral Palsy have Spastic Cerebral Palsy.

Spastic Cerebral Palsy is characterized by at least two of the following symptoms, which may be unilateral (hemiplegia) or bilateral:

Traditionally we recognized three types of spastic Cerebral Palsy: Hemiplegia, Diplegia and Quadriplegia.

With hemiplegia, one side of the body is involved with the upper extremity generally more affected than the lower. Seizure disorders, visual field deficits, astereognosis, and proprioceptive loss are likely. Twenty percent of children with spastic Cerebral Palsy have hemiplegia. A focal traumatic, vascular, or infectious lesion is the cause in many cases. A unilateral brain infarct with posthemorrhagic porencephaly can be seen on Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI).

With diplegia, the lower extremities are severely involved and the arms are mildly involved. Intelligence usually is normal, and epilepsy is less common. Fifty per cent of children with Spastic Cerebral Palsy have diplegia. A history of prematurity is usual. Diplegia is becoming more common as more low- birth-weight babies survive. MRI reveals mild Periventricular Leukomalacia (PVL).

With quadriplegia, all four limbs, the trunk and muscles that control the mouth, tongue and pharynx are involved. Thirty percent of children with Spastic Cerebral Palsy have quadriplegia. More serious involvement of lower extremities is common in premature babies. Some have perinatal hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. MRI reveals Periventricular Leukomalacia (PVL). Abnormal movements that occur when the child initiates movement are named Dyskinesias. Dysarthria, Dysphagia and drooling accompany the movement problem. Intellectual development is generally normal, however severe dysarthria makes communication difficult and leads the outsider to think that the child has intellectual impairment. Sensorineural hearing dysfunction also impairs communication. Dyskinetic Cerebral Palsy accounts for approximately 10% to 15 % of all cases of Cerebral Palsy. Hyperbilirubinemia or severe anoxia causes basal ganglia dysfunction and results in Dyskinetic Cerebral Palsy. Dyskinetic Cerebral Palsy is characterised by the following Symptoms:

Dyskinetic Cerebral Palsy may be either:

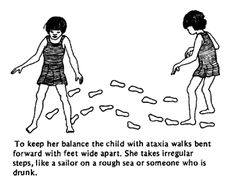

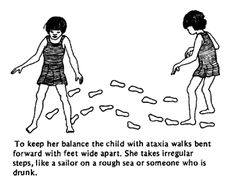

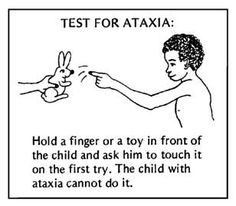

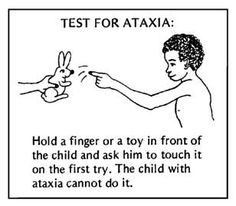

Ataxia is loss of balance, coordination and fine motor control. Ataxic children cannot coordinate their movements. They are hypotonic during the first 2 years of life. Muscle tone becomes normal and ataxia becomes apparent toward the age of 2 to 3 years. Children who can walk have a wide-based gait and a mild intention tremor (Dysmetria). Dexterity and fine motor control is poor. Ataxia is associated with cerebellar lesions. Ataxia is often combined with spastic diplegia. Most ataxic children can walk but some need walkers. Ataxic Cerebral Palsy is characterized by the following symptoms:

Definition

Time Frame of Brain Injury

Epidemiology

Aetiology

Risk Factors

Classification of Cerebral Palsy

Rosenbaum et al. [9] proposed that children with Cerebral Palsy continue to be classified by the predominant type of tone or movement abnormality (categorised as spasticity, dystonia, choreoathetosis, or ataxia) and that any additional tone or movement abnormalities present be listed as secondary types and to record the anatomical distribution of features.Sub-types of Cerebral Palsy

Anatomical Classifications

Spacticity

Hemiplegia (Unilateral)

Diplegia (Bilateral)

Quadriplegia (Bilateral)

Dyskinetic CP

Ataxic CP

|

|

Mixed CP

Children with a mixed type of Cerebral Palsy commonly have mild spasticity, dystonia and/or athetoid movements. Ataxia may be a component of the motor dysfunction in children in this group. Ataxia and spasticity often occur together. Spastic Ataxic Diplegia is a common mixed type that often is associated with hydrocephalus.

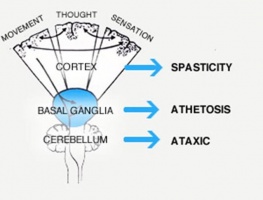

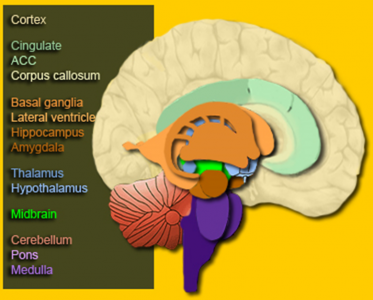

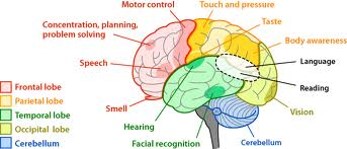

The Brain

Here is some of the clinical terminology used when talking about Cerebral Palsy:

- Tonus

- Lesion Site

- Spastic

- Cortex

- Dyskinetic

- Basal Ganglia – Extrapyramidal System

- Hypotonic / Ataxic

- Cerebellum

- Mixed

- Diffuse

Knowing where the damage could be located will not influence your interventions. Look at the following pictures of the brain to understand the relationship between the location of the damage and the symptoms.

Problems Regularly Seen with Children with Cerebral Palsy

This table highlights the problems that children with Cerebral Palsy experience within different areas.

| Neurological | Musculoskeletal | Associated Problems |

|---|---|---|

|

|

This image gives a nice pictorial overview of the problems experienced by children with Cerebral Palsy.

Associated Problems

Cerebral Palsy in itself can significantly impact upon the child. Many associated conditions also need to be managed. As a Health Care Professional it is essential to also understand these associated conditions and think about how these might impact or influence your management strategies when working with the child.

Diagnosis

Cerebral palsy is one of the main causes of childhood disabilities, with many different signs, symptoms, and challenges. There is no one test to confirm if a child has cerebral palsy or something else. There is no blue print of interventions for a child with cerebral palsy and each child is different and unique. Classification of gross motor, fine motor and communication will help medical professionals and the family to better understand the abilities of the child and what to focus on for interventions.

The diagnosis of cerebral palsy is based on a clinical description. The diagnosis is not based on the result of a (biological) test or on imaging findings. Consequently, the diagnosis can be subject to some degree of variability. This means that two paediatricians may disagree on a diagnosis of Cerebral Palsy for the same child. It is sometimes difficult for even professionals to differentiate between bilateral Spastic Cerebral Palsy and Dyskinetic Cerebral Palsy.

Ideally, a paediatrician or neurologist will give the diagnosis but some children with Cerebral Palsy in developing countries have never seen a doctor. There are also many children in developing countries with Cerebral Palsy who have seen many doctors previously but with no good explanation of the meaning and consequences of the diagnoses.

Life Expectancy

Mortality in Cerebral Palsy is extremely variable. Life expectancy is normal in most diplegic and hemiplegic children who receive adequate medical care and have strong family support. Some severely affected quadriplegics die of malnutrition, infections or respiratory problems before reaching adolescence. In some very poor and poor resource areas children with cerebral palsy may not reach the age of 5 years.

Interventions with Cerebral Palsy

The aim and types of interventions are unique for each child with Cerebral Palsy because their needs are all different depending on the level of disability. This table gives a great overview of the aims of treatment/interventions for each level of disability.

| Mild | Moderate | Severe |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention will focus of appearance and integration | Intervention will focus on independence and self-care skill | Intervention will focus on comfort and enhanced care |

Communication

Communication is necessary to express thoughts, feelings, and needs. Every individual with Cerebral Palsy needs a way to communicate to be part of the family and the community. If the child can produce comprehensible sounds and syllables by 2 years of age, they will probably have normal verbal communication but considerations need to be made for those whose communication skills are severely affected. Alternative methods such as communication methods such as simple communication boards in children who have difficulty speaking.

Activities of Daily Living (ADL)

Activities of daily living are self-care activities such as feeding, toileting, bathing, dressing, and grooming in addition to meal preparation and household maintenance. Dyskinetic and total body involved children have problems of dexterity and fine motor control that prevent independence in activities of daily living. Hemiplegic and diplegic children can become functional in these areas. They sometimes need help of (occupational) therapy. Family attitude is a critical factor determining the level of independence of a child. Overprotection results in a shy and passive individual who has not gained self-care abilities.

Mobility

Children have to explore their surroundings to improve their cognitive abilities. Mobilisation is crucial for the young child with a disability to prevent secondary mental deprivation. The use of wheelchairs or other mechanical assertive devices can help to promote independent mobility in the community if the child cannot mobilize through walking. Mobility is important to function in the fast paced societies and people who have difficulty moving are always at a disadvantage. In the adult, becoming an independent member of the society and earning a living depends upon independent mobility. Families view ambulation as the most important issue during childhood. Every effort must be made to increase the child’s ability to walk; however, walking depends more on the extent of the child’s neurological impairment rather than the amount of physical therapy, surgery or bracing that they receive. The child can achieve his/her own maximum potential with practice.

Focus on ambulation should not result in neglecting communication and cognitive development. Priorities change in adolescence as they need education, independence, and an active social life. Although ambulation is still important, it is needed less to function. Learning how to use computers may benefit the adolescent in the long term rather than being able to take a few assisted steps.

Mobility is important for the child, whereas social identity and independence are more valuable for the adolescent.

International classification of functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) can be used to describe the treatment approach in CP. PLease see the link below to understand better.

References

- ↑ SCPE. Dev Med Child Neurol 42 (2000) 816-824

- ↑ 2.02.1 Morris C. Definition and classification of cerebral palsy: a historical perspective. Dev Med Child Neurol Suppl. [Historical Article]. 2007 Feb;109:3-

- ↑ Love SC, Novak I, Kentish M, Desloovere K, Heinen F, Molenaers G, et al. Botulinum toxin assessment, intervention and aftercare for lower limb spasticity in children with cerebral palsy: international consensus statement. Eur J Neurol. [Consensus Development Conference Practice Guideline]. 2010 Aug;17 Suppl 2:9-37

- ↑ 4.04.1 Hagberg B HG, Olow I. The changing panorama of cerebral palsy in Sweden 1954-1970. I. Analysis of the general changes. Acta Paediatr Scand 1975;64(2):187-92

- ↑ Johnson A. Surveillance of cerebral palsy in Europe: a collaboration of cerebral palsy surveys and registers. Surveillance of Cerebral Palsy in Europe (SCPE). Dev Med Child Neurol. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. 2000 Dec;42(12):816-24

- ↑ Lenski M, Bishai SK, Paneth N. Disability information improves the reliability of cerebral palsy classification. Dev Med Child Neurol. [Comment Letter]. 2001 Aug;43(8):574-5

- ↑ Gainsborough M, Surman G, Maestri G, Colver A, Cans C. Validity and reliability of the guidelines of the surveillance of cerebral palsy in Europe for the classification of cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. 2008 Nov;50(11):828-31

- ↑ Rosenbaum P, Paneth N, Leviton A, Goldstein M, Bax M, Damiano D, et al. A report: the definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006. Dev Med Child Neurol Suppl. 2007 Feb;109:8-14

- ↑ Bax M, Goldstein M, Rosenbaum P, Leviton A, Paneth N, Dan B, et al. Proposed definition and classification of cerebral palsy, April 2005. Dev Med Child Neurol. [Review]. 2005 Aug;47(8):571-6

- ↑ Emma Giles. Khan Academy – Types of Cerebral Palsy Part 1: Spastic. Available from: ↑ Emma Giles. Khan Academy – Types of Cerebral Palsy Part 2: Dyskinetic & Ataxic. Available from: function gtElInit() { var lib = new google.translate.TranslateService(); lib.setCheckVisibility(false); lib.translatePage('en', 'pt', function (progress, done, error) { if (progress == 100 || done || error) { document.getElementById("gt-dt-spinner").style.display = "none"; } }); }

Ola!

Como podemos ajudar?