Definition/Description

Injury to the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) can range from a stretch to a total tear or rupture of the ligament. These injuries are less common than anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries as the PCL is broader and stronger.[1]

Clinically relevant anatomy

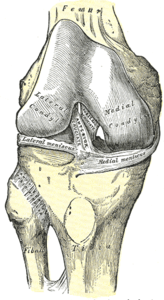

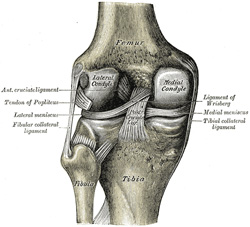

The PCL is one of the two cruciate ligaments of the knee. It acts as the major stabilizing ligament of the knee. and prevents the tibia from excessive posterior displacement in relation to the femur. It also functions to prevent hyper-extension and limits internal rotation, adduction and abduction at the knee joint.[1] The PCL is twice as thick as the ACL which results in less injuries than the ACL due to the stronger nature. As a result, PCL injuries are less common than ACL injuries.

It originates at the internal surface of the medial femoral condyle and inserts on the center of the posterior aspect of the tibial plateau, 1 cm below the articular surface of the tibia[1][2]. It crosses the ACL to form an ‘X’. The PCL consists of two inseparable bundles: the wide anterolateral (AL) bundle and the smaller posteromedial (PM) bundle.[1] The AL bundle is most tight in mid-flexion and internal rotation of the knee, while the PM bundle is most tight in extension and deep flexion of the knee. The orientation of the fibers varies between bundles. The AL bundle is more horizontally orientated in extension and becomes more vertical as the knee is flexed beyond 30°. The PM bundle is vertically orientated in knee extension and becomes more horizontal through a similar range of motion.[1][2]

Epidemiology/Etiology

Epidemiology

The mean age of people with acute PCL injuries range between 20-30’s. Injuries to the PCL can occur isolated, mostly as a result of sport, as well as combined (see multi-ligament knee injuries), usually caused by motor vehicle accidents.[3]

A 2% incidence is estimated for PCL injuries, and it can range from 3,5-20% for operated, isolated and combined PCL injuries.[1]

Etiology

The most frequent mechanism of injury is a direct blow to the anterior aspect of the proximal tibia on a flexed knee with the ankle in plantarflexion[3]. This often occurs as dashboard injuries (posterior force to the tibia in a flexed knee) during motor vehicle accidents and results in posterior translation of the tibia. Hyper-extension and rotational or varus/valgus stress mechanisms may also be responsible for PCL tears.[1][4][5] These injuries occurs mostly during sports such as football, soccer and skiing. Isolated PCL injuries are commonly reported in athletes, with hyper-flexion being the most frequent mechanism of injury.[4][6] Further mechanisms of PCL injury include bad landings from a jump, a simple misstep or fast direction change.[4][5]

Characteristics/Clinical presentation

Characteristics

PCL injuries present in different degrees according to the severity.

Grade 1: Limited damage with only microscopic tears in the ligament, mostly as the result of an overstretch. It is still able to function and stabilize the knee.[7]

Grade 2: The ligament is partially torn. There is a feeling of instability[7].

Grade 3: Complete ligament tear or rupture. This type of injury is mostly accompanied by a sprain of the ACL and/or collateral ligaments.[1][7]

Clinical presentation

A distinction can be made between the symptoms of an acute and chronic PCL injury[8].

Acute PCL injury

Symptoms are often vague and minimal, with patients often not even feeling or noticing the injury.[1][2][8] Minimal pain, swelling, instability and full range of motion is present, as well as a near-normal gait pattern.[1][2][8]

- Combination with other ligamentous injuries:

Symptoms differ according to the extent of the knee injury. This includes swelling, pain, a feeling of instability, limited range of motion and difficulty with mobilisation. Bruising may also be present.[1]

Chronic PCL injury

Patients with a chronic PCL injury are not always able to recall a mechanism of injury. Common complaints are discomfort with weight-bearing in a semi flexed position (e.g. climbing stairs or squatting) and aching in the knee when walking long distances. Complaints of instability are also often present, mostly when walking on an uneven surface[8]. Retropatellar pain and pain in the medial compartment of the knee may also be present[8]. Potential swelling and stiffness depend on the degree of associated chondral damage.[8]

Differential diagnosis

Uncommon:[9]

Diagnostic procedures

Physical examination

- Neurovascular examination to rule out concurrent injuries[10]

- Palpation: Minimum/no swelling in isolated injury [11]

- Muscle power

- Range of motion

Special tests

- Posterior drawer: One of the most accurate tests for PCL injury and can only be executed when there is no swelling in the knee joint[1][4]

- Posterior Lachman test: A slight increase in posterior translation indicates a posterolateral ligament complex injury[2][4]

- Special tests to rule out concurrent knee injuries:[1][2][4]

- Varus/Valgus stress tests

- External rotation recurvatum test

- Reverse pivot shift test

Special investigations

- X-rays:

- AP, tunnel, sunrise, stress and a lateral views (best to detect lateral sag)

- X-rays can be done in different positions, e.g. standing and weight-bearing with 45° knee flexion

- Assists in early identification of PCL avulsion fractures

- Chronic: Assess joint space narrowing (preferably including weight-bearing and sunrise views)

- MRI:

- Acute: Determine grade of injury, as well as evaluating other potentially injured structures (e.g. ligaments, meniscus and/or cartilage structures of the knee)

- Chronic: MRI may appear normal in grade I and II injures

- Bone scans: Best in chronic cases with recurrent pain, swelling and instability.

- Detect early arthritic changes before MRI or Xray. These patients have a higher risk of developing articular cartilage degenerative changes, shown by areas of increased radiotracer uptake, most commonly in the medial and patellofemoral compartments.

- Ultrasound: More cost effective than MRI for evaluation

- Arteriogram: Evaluate the vascular status in the limb

Outcome measures

Medical management

Conservative management

Non-operative treatment are normally used for an acute, isolated grade I or II PCL sprains, if it fits the following criteria:[1][5][10]

- Posterior drawer

- Decrease in posterior drawer excursion with internal rotation on the femur

Grade I and II PCL tears usually recover rapidly and most patients are satisfied with the outcome. Athletes are normally ready for return to play within 2-4 weeks.[6][10] Management includes:[1][10][11]

- Immobilize the knee in a range of motion brace locked in extension for 2-3 weeks

- Assisted weight-bearing (partial to full) for 2 weeks

- Physiotherapy

An acute grade III injury can also be managed conservatively. Immobilization in a range of motion brace in full extension is recommended for two to four weeks, due to the high probability of injuries to other posterolateral structures. The posterior tibial sublaxation caused by the hamstring is minimized in extension, causing less force to the damaged PCL and posterolateral structures.[6][10] This allows the soft tissue structures to heal. Physiotherapy is recommended as part of the conservative management.[1] Return to play after conservative management of grade III tears is normally between 3 and 4 months.[6][10]

Chronic isolated grade I & II PCL injuries are usually managed conservatively with physiotherapy. Activity modification is recommended in chronic cases with recurrent pain and swelling.[1]

Surgical management

The primary objective during a PCL reconstruction is to restore normal knee mechanics and dynamic knee stability, thus correcting posterior tibial laxity.[6][10] There are different options of the optimal surgical approach for a PCL reconstruction. Debate exists about the best graft type or source, placement of the tibia, femoral tunnels, number of graft bundles and the amount of tension on the bundles.[6]

When using a double bundle graft, both bundles of the PCL can be reconstructed. A single bundle graft reconstructs only the stronger anterolateral bundle. The double bundle approach can restore normal knee kinematics with a full range of motion, while the single bundle only restores the 0°-60° knee range.[10]

Types of grafts include:[6]

- Allograft (mostly Achilles tendon): Decreased surgical time and the absence of iatrogenic trauma to the harvest site. The Achilles tendon graft produces a large amount of collagen and ensures a complete filling of the tunnels. This is normally used to reconstruct the AL bundle. The AL graft is tensioned and fixed at 90° knee flexion.[10]

- Autologous tissue:

- Bone-patellar tendon-bone: Most common, as the bone plugs allow sufficient fixation of the tissue. The disadvantages of this graft are the harvest site morbidity and as a result of the rectangular form of the graft, the tunnels can not be completely filled with collagen.

- Quadrupled hamstring: Decreases the morbidity factor, but results in an inferior fixation method. A double semitendinosus tendon autograft is normally used for the PM bundle reconstruction. The PM graft is tensioned and fixed at 30° knee flexion.

- Quadriceps tendon: Has morbidity factor and adequate biomechanical properties.

Acute PCL injury

Surgical reconstruction of the PCL is recommended in acute injuries with severe posterior tibia subluxation and instability, if the posterior translation is greater than 10mm or if there are multiple ligamentous injuries. PCL avulsion fracture injuries fractures heal well when operated early on.[6][10] High demand individuals, such as young athletes, are normally treated with surgery as soon as possible, to enhance the chances to return to full functional capacity.[11] Grade III injury of the PCL are mostly combined with other injuries, and thus surgical reconstruction of the ligaments will have to be done, often within 2 weeks from the injury. This time frame gives the best anatomical ligament repair of the PCL and less capsular scarring.

Chronic PCL injury

Surgical intervention are recommended in chronic cases, considering the following (mostly in grade III injuries):[1][10]

- Recurrent pain and swelling

- Positive bone scan with the patient being unable to modify his/her activities

- In cases where combination injuries are present, surgery is indispensable

Surgical procedure

- Tibial inlay procedure: Starts with a diagnostic arthroscopy, but the inlay itself is an open surgery. The femoral tunnels are established with an outside-in technique to closely duplicate the femoral insertion of the PCL-meniscofemoral ligament complex. The graft is prepared during the exposure. Then it is placed in the graft passer and passed through the femoral tunnel, tensioned and screwed to the bone.

- Limiting knee range of motion bracing is needed after the surgery (see physiotherapy management).

- Tibial tunnel method: Arthroscopical approach. A guide pin is drilled from a point just distal and medial to the tibial tubercle and aimed at the distal and lateral aspect of the PCL footprint. The femoral tunnel should be placed just under the subchondral bone, to reduce the risk of osteonecrosis. The direction of the graft passage depends on the type of graft used. The tibial inlay procedure avoids this difficult part. The graft is placed in 70° to 90° flexion. In the single bundle reconstruction only 1 tunnel is drilled. In a double-bundle reconstruction two tunnels are drilled, which is technically more challenging.[6][10]

Complications

Possible complications after or during a PCL reconstruction include:[6]

- Fractures

- Popliteal artery injury

- Deep vein thrombosis

- Residual laxity (can be caused by an undiagnosed non-isolated PCL injury)

- Decrease range of motion (can be caused by improper placement or too much tension of the graft).

- Manipulation under anesthesia can be considered to improve range of motion if physiotherapy is unsuccessful

Physiotherapy management

Conservative management

Grade 1 & II injuries

Two weeks of relative immobilization of the knee (in a locked range of motion brace) is recommended by orthopaedic surgeons. Physiotherapy in this time period includes:[1][4][6][10]

- Partial to full weight-bearing mobilisation

- Reduce pain and inflammation

- Reducing knee joint effusion

- Restore knee range of motion

- Knee strengthening (especially protective quadriceps rehabilitation)

- Strengthening the quadriceps is a key factor in a successful recovery, as the quadriceps can take the place of the PCL to a certain extent to prevent the femur from moving too far forward over the tibia.

- Hamstring strengthening can be included

- Important to incorporate eccentric strengthening of the lower limb muscles

- Closed chain exercises

- Activity modification until pain and swelling subsides

After 2 weeks (on the orthopaedic surgeon’s recommendation):[4]

- Progress to full weight-bearing mobilisation

- Weaning of range of motion brace

- Proprioception, balance and coordination

- Agility programme when strength and endurance has been regained and the neuromuscular control increased

- Return to play between 2 and 4 weeks of injury

Grade III injuries

The knee is immobilised in range of motion brace, locked in extension, for 2-4 weeks. Physiotherapy management in this time includes:

- Activity modification

- Quadriceps rehabilitation

- Initially isometric quadriceps exercises and straight-leg raises (SLR)

- Avoid isolated hamstring strengthening

- Active-assisted knee flexion

- Progress weight-bearing within pain limits

- Quadriceps rehabilitation: Promote dynamic stabilization and counteract posterior tibial subluxation

- Closed chain exercises

- Open kinetic chain eccentric excercises and eventually

- Progress to functional exercises such as stationary cycling, leg press, elliptical exercises and stair climbing

Return to play is sport specific, and only after 3 months.[4]

Chronic injuries

Chronic PCL injuries can be adequately treated with physiotherapy. A range of motion brace is used, initially set to prevent the terminal 15° of extension. After a while the brace is opened to full extension.[10]

Post-operative rehabilitation

Post-operative rehabilitation typically lasts 6 to 9 months. The duration of each of the five phases and the total duration of the rehabilitation depends on the age and physical level of the patient, as well as the success of the operation. Also see page on PCL reconstruction.

Phase I: Post-operative phase

- Bracing:

- Range of motion brace locked in full extension (to protect PCL graft)

- Brace may be unlocked when sitting and for exercises

- Unlocked after 4 weeks

- Functional PCL brace after 4-6 weeks

- Range of motion brace locked in full extension (to protect PCL graft)

- Weight-bearing as tolerated mobilisation

- Progress to unassisted mobilisation when functional PCL brace is fitted

- RICE-method for knee effusion:

- Rest

- Ice: 10-20 minutes every 2-4 hours

- Elevation

- Compression

- Exercises (0° to 90°):

- Passive knee flexion:

- Active knee extension:

- 10-25 repetitions, 3-4x/day

- Patella mobilisations in all directions to prevent arthrofibrosis

Phase II: Maximum protection phase

- Continued with RICE-metod

- Knee range of motion to 0° tot 120°

- Full unassisted weight-bearing, if:

- Good quadriceps control

- No extension lag during SLR

- Full extension range of motion

- Ability to do single leg stance without pain or unsteadiness

- Non-antalgic gait

- Normalize gait pattern, especially the loading and stance phases with quadriceps activation.

- Exersises:

- Open chain knee extension exercises (0°-70°)

- Closed chain weight bearing exercises (range 0°-45°):

- Bilateral and unilateral leg press

- Stationary cycling once knee flexion >100°

- Hydrotherapy

- SLR using maximum resistance of 10% of the body weight

- Mini-squats (0°-45°) – progress from double to single leg

Phase III: Controlled ambulation phase

- Bilateral to unilateral closed chain exercises (0°-45°)

- Wall squatting, single leg squats and lunges

- Increase resistance

- Increase range of motion.

- Other exercises:

- Balance and proprioceptive drills

- Forward and lateral step-ups

- Stair climbing

- Treadmill walking

- Pool jogging are performed during this phase.

- Resisted knee flexion exercises should ONLY be done at the end of this phase

- Discontinue knee brace in the first half of this phase

Phase IV: Light activity phase

- Progress walking to running on the following criteria:

- Normal gait

- 0°-120° knee range of motion

- No joint effusion

- Ability to do single leg hops without pain

- Walking tolerance of minimum 25 minutes

- Light agility drills:

- Line hops, bounding and ladder drills.

- Exercises:

- Improve range of motion, speed, resistance and/or volume or duration of the exercises

- Continue knee and hip strengthening exercises, including:

- Open chain quadriceps exercises (90°-0°)

- Open chain hamstring excercises (0°-45°)

- Closed chain squatting and lunging (0°-75°).

- Initiate swimming and agility drills in water

Phase V: Return to sport

- Criteria for progression to phase V:

- Hop test with an outcome of minimum 80% compared to the unaffected leg

- Exercises:

- Increase strengthening exercises and neuromuscular control demands.

- E.g. multi-directional lunges, single leg stance with perturbation, running, change of direction drills and bench/box jumps

- Sport specific activities to incorporate movements in the sagittal, frontal and transverse planes

- Closed chain exercises (0°-90°)

- Open chain hamstring exercises (0°-60°)

- High impact activities can be performed in this phase, 2-4x/week

- Increase strengthening exercises and neuromuscular control demands.

- Return to sport:

- Hop test: Minimum 90% compared to the unaffected limb.

- Observe jumping and landing of the patient to avoid hyperextension and varus or valgus angulation

- Functional knee brace may be used to increase proprioception and facilitate normal knee mechanics during running and pivoting activities.

- Hop test: Minimum 90% compared to the unaffected limb.

- Discharge from physiotherapy with home exercise programme

Resources

Clinical bottom line

PCL injuries are mostly caused by hyper-flexion and injuries do not occur frequently. This is due to the strength of the ligament and the fact that hyper-flexion, possible through a force to the anterior aspect of the proximal tibia, does not commonly occur. PCL injuries will mostly happen during sports, such as football, soccer and skiing. Another possible mechanism of injury can be a car accident, resulting in a ‘dashboard injury’. The severity is divided in three degrees and an acute injury is distinguished from a chronic injury. Clinical presentation will depend on the degree and the condition of the injury. If symptoms are observable, these usually include swelling, pain, a feeling of instability, limited range of motion and difficulty with mobilisation. The treatment depends on the grade and the individual patient. A grade I and II injury are usually treated non-surgically, unless it occurs in an young athlete or high demand individual. A grade III injury is usually treated by a surgical intervention, however non-surgical treatment is also possible. Physiotherapy plays a role in conservative management, as well as post-operative rehabilitation. Both rehabilitation programs focus on the quadriceps muscle group, because of its ability to partially take over the function of the PCL. The structure and the build-up of the rehabilitation program depends on the degree of the injury, the individual patient and the success of the operation (if applicable).

References

- ↑ 1.001.011.021.031.041.051.061.071.081.091.101.111.121.131.141.151.161.171.181.191.201.211.221.23 Medscape. Drugs & Diseases, Sport Medicine. Posterior Cruciate Ligament Injury. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/90514-overview (accessed 20/08/2018).

- ↑ 2.02.12.22.32.42.52.6 Paulsen F, Waschke J, Sobotta. Lower extremities, Knee Joint. Elsevier, 2010. p 272-276.

- ↑ 3.03.1 Schulz MS, Russe K, Weiler A, Eichhorn HJ, Strobel MJ. Epidemiology of posterior cruciate ligament injuries. Archives of orthopaedic and trauma surgery 2003;123(4):186-91.

- ↑ 4.004.014.024.034.044.054.064.074.084.094.104.114.124.134.144.154.164.174.18 Lee BK, Nam SW. Rupture of Posterior Cruciate Ligament: Diagnosis and Treatment Principles. Knee Surgery and Related Research 2011 Sep;23(3):135-141.

- ↑ 5.05.15.2 American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Diseases & Conditions: Posterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries. http://orthoi/nfo.aaos.org/topic.cfm?topic=a00420 (accessed 20/08/2018).

- ↑ 6.006.016.026.036.046.056.066.076.086.096.106.116.126.13 Fowler PJ, Messieh SS. Isolated posterior cruciate ligament injuries in athletes. The American Journal of Sports Medicine 1987;15(6):553–557.

- ↑ 7.07.17.2 Malone AA, Dowd GSE, Saifuddin A. Injuries of the posterior cruciate ligament and posterolateral corner of the knee. Injury 2006;37(6):485-501.

- ↑ 8.08.18.28.38.48.5 Bisson LJ, Clancy Jr WG. Chapter 90: Isolated posterior cruciate ligament injury and posterolateral laxity. In: Chapman’s Orthopaedic Surgery. 3rd edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 2001.

- ↑ 9.09.1 British Medical Journal Best Practice. Evaluation of knee injury. https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-us/575 (accessed: 22/08/2018).

- ↑ 10.0010.0110.0210.0310.0410.0510.0610.0710.0810.0910.1010.1110.1210.1310.1410.1510.16 Wind WM, Jr, Bergfeld JA, Parker RD. Evaluation and treatment of posterior cruciate ligament injuries: revisited. The American Journal of Sports Medecine 2004, 32(7):1765–1775.

- ↑ 11.011.111.2 Walters J, editor. Orthopaedics – A guide for practitioners. 4th Edition. Cape Town: University of Cape Town, 2010.