Introduction

Spina bifida is a variable defect in which the vertebral arch of the spinal column is either incompletely formed or absent. The term Bifida is from the Latin word Bifidus, or “left in 2 parts.” It is classified as a defect of the neural tube (i.e. the embryonic structure that develops into the spinal cord and brain). Neural tube defects have a range of presentations, from stillbirth to incidental radiographic findings of spina bifida occulta. The term myelodysplasia has been used as a synonym for Spina bifida.[1][2]Lesions most commonly occur in the lumbar and sacral regions but can be found anywhere along the entire length of the spine.[1] It is a treatable spinal cord malformation that occurs in varying degrees of severity.[2]

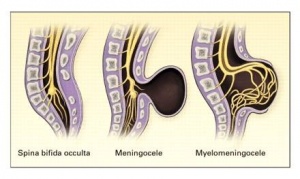

Types of Spina Bifida

Spina bifida occulta: It can occur without neurologic defects.

Meningocele: A cystic swelling of the dura and arachnoid, protrudes through the spina bifida defect in the vertebral arch.

Meningomyelocele: when cord tissue extends into the meningocele.

Myeloschisis: If the spinal cord is exposed on the surface of the back, the condition is called myeloschisis [3]

Embryology

Neural tube defects occur between the 17th and 30th day of gestation. This defect then disrupts all of the overlying tissues, preventing the vertebral arch from closing.[4]If the posterior vertebral arch and overlying tissues do not form normally, the normal spinal cord and meninges may then herniate out through the defect and cause a meningomyelocele (MMC) .If the vertebral arch fails to grow and fuse normally and the spinal cord and meninges are not disturbed spina bifida occulta results.[2]

Pathophysiology

MMC is associated with abnormal development of the cranial neural tube, which results in several characteristic CNS anomalies. The Chiari type II malformation is characterized by cerebellar hypoplasia and varying degrees of caudal displacement of the lower brainstem into the upper cervical canal through the foramen magnum. This deformity impedes the flow and absorption of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and causes hydrocephalus, which occurs in more than 90% of infants with MMC. Numerous other associated nervous system malformations include syringomyelia, diastematomyelia, and agenesis of the corpus callosum. Non-neurologic associations include spine malformations, hydronephrosis, cardiac defects, and gastrointestinal anomalies.[2]

Epidemiology

There are variations in incidence between some racial populations. The incidence of MMC in America: 1.1 in 1000 births. The current incidence in America is about 0.6 per 1000, and there is good evidence that this has been steadily declining.[5] African-American cases are often a third of those found for white Americans, while those for Hispanic-Americans are two to three times greater[2].1 case in 10,000 is reported in Finland and 5 in 1000 in Northern Ireland 5. There are at least 2000 cases/year in the US [5]

Aetiology

The risk of an adult with MMC having a child with a neural tube defect is 5% [6]. Women with low RBC cell folate levels during early pregnancy have up to a 6x greater risk of having a child with a neural tube defect. Intrauterine exposure to antiepileptic drugs, particularly valproate and carbamazepine, and to drugs used to induce ovulation. Maternal exposures to fumonisins, EM fields, hazardous waste sites, disinfection by-products found in drinking water, and pesticides.[2]Other risk factors for MMC include maternal obesity, hyperthermia (as a result of maternal fever or febrile illness or the use of saunas, hot tubs, or tanning beds), and maternal diarrhoea.[6]

Diagnostic Procedures

Measurement of maternal serum α-fetoprotein (MSAFP) levels is a common screening test. If the level is elevated, indicating that any portion of the fetus is not covered by skin, this screening test is then followed by detailed ultrasonography. Ultrasound scans will diagnose 92% of neural tube defects. Mothers with elevated MSAFP levels and a normal appearing ultrasound scan may be evaluated by amniocentesis for the presence of elevated acetylcholinesterase levels in the amniotic fluid.[2]

Outcome Measures

The Functional independence measure (FIM) is the most widely accepted functional measure. FIM consists of 18 scales scored from 1 to 7; higher numbers mean greater ability. Others include the Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ), Barthel Index (BI).

Management / Interventions

Generally, surgery follows within the first few days of life to close the spinal cord defect.[2] It is also important to prevent infection and additional trauma to the exposed tissues. Additional surgeries may be required to manage other problems in the feet, hips, or spine. The individuals with hydrocephalus will also require subsequent surgeries due to the shunt needing to be replaced. Due to the bowel and bladder problems that are often caused by the neural tube defect, catheterization may be necessary.

The Management of Myelomeningocele Study (MOMS).[7]The MOMS trial is an NIH-sponsored multicenter clinical trial which began in 2002 to evaluate what was the best treatment for myelomeningocele — fetal surgery or surgical repair after birth.

The clinical trial results showed prenatal surgery significantly reduced the need to divert, or shunt, fluid away from the brain; improved mental development and motor function; and increased the likelihood that a child will walk unassisted. The MOMS trial has proved that some of the factors causing problems like Chiari II malformation and hydrocephalus are in fact those that develop during the second half of pregnancy. Closing the fetus’s back early may allow some nerve function to be restored in pregnancy, and actually, reverse the development of this serious condition.

Physiotherapy Management

A multidisciplinary approach towards managing patients with MMC is essential for successful outcomes. The patient should be assessed as soon after birth as possible. At different stages, the focus of physiotherapy will change with the changing needs of the patient. Regular review is essential to meet up with patient needs. Parents and caregivers should be involved in patient care.

- CLINICAL PRESENTATION – The following can be observed in the case of MMC.[2]Flaccid or spastic paralysis of the lower limbs, Urinary and or faecal incontinence, Hydrocephalus, Poor trunk control, Musculoskeletal complications, Scoliosis, Hip dysplasia, Hip dislocation, Hip/knee contracture, Clubfoot, Muscle Atrophy

- PHYSICAL ASSESSMENT- The following may be observed during the physical assessment.

- Open wound

- Deformities

- Skin abnormalities

- Sensation

- Muscle tone

- Muscle Strength

- Range of Motion

- Contractures

- Dislocation

- Developmental Milestones

- PLAN OF CARE

- Prevent/correct deformity

- Maintain/improve physiological properties of joints and muscles

- Monitor normal motor development

- Educate parent(s), caregivers

- Encourage and maximise independent mobility

- Encourage participation in regular physical activity.

- MEANS OF TREATMENT

- Serial casting (CTEV)

- Passive mobilization, graded exercises and stretches.

- Tactile stimulation

- Balance & Trunk control exercises

- Positioning

- Orthosis & Assistive devices

- Parent education: Parents should be educated about the child’s condition, progress, and prognosis and involved in treatment planning and home programmes.[8] Serial casting for CTEV.

Complications

Common Complications of MMC Include the Following.[2]

- Reproductive organs impairment

- Neurogenic Bladder: The vast majority of children with MMC have a neurogenic bladder.

- Only 5.0% to 7.5% of the MMC population have a normal urologic function.

- Neurogenic Bowel: Traditional bowel continence is present in approximately 10% of children with MMC.

- Musculoskeletal complications.

- Psychosocial issues: Vulnerable child syndrome.

- Pressure sores

- Learning disabilities

Neurosurgical Complications

- Wound infection rates range from 7% to 12% [2]

- Hydrocephalus; visual impairment

- Ventriculitis: low subsequent IQ

- Shunt failure

- 5% – 32% of infants with MMC will present with signs of Chiari compression, making it the most common cause of death in patients with MMC

- Chiari compression can occur at any time, presentation in the first year of life is associated with up to 50% mortality.[9]

- Chronic headaches are the most frequently reported symptom.[9]

- Obesity – Obesity is prevalent in children with MMC. The higher the level of the lesion along the spine the higher her percentage of body fat.[2]In children with L1–L3 lesions, the effect of increasing obesity is a critical factor in the loss of ambulation[2]Typically, children with MMC reach their peak ambulatory abilities around the age of 10 years. They then experience a slow decline in function over the next 10 years. The children who ambulate more have a lower percentage of body fat. [2]

Conclusion

About 90% of babies born with Spina Bifida now live to be adults, about 80% have normal intelligence and about 75% play sports and do other fun activities.

Most do well in school, and many play sports.[2]

References

- ↑ 1.01.1 Lundy-Ekman L (2007). Neuroscience: Fundamentals for Rehabilitation. 3rd edition. St. Louis: Saunders, 2007

- ↑ 2.002.012.022.032.042.052.062.072.082.092.102.112.122.132.14 Spina Bifida: Background, Pathophysiology, Etiology [Internet]. Emedicine.medscape.com. 2019 [cited 2 March 2019]. Available from: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/311113-overview

- ↑ 4. Burke R, Liptak G. Providing a Primary Care Medical Home for Children and Youth With Spina Bifida. PEDIATRICS. 2011;128(6):e1645-e1657.

- ↑ Fletcher JM, Copeland K, Frederick JA (2005). Spinal lesion level in spina bifida: a source of neural and cognitive heterogeneity. Journal of Neurosurgery. 102(3 Suppl):268-79

- ↑ 5.05.1 5. Shin M, Besser L, Siffel C, Kucik J, Shaw G, Lu C et al. Prevalence of Spina Bifida Among Children and Adolescents in 10 Regions in the United States. PEDIATRICS. 2010;126(2):274-279.

- ↑ 6.06.1 6. Canfield M, Ramadhani T, Shaw G, Carmichael S, Waller D, Mosley B et al. Anencephaly and spina bifida among Hispanics: Maternal, sociodemographic, and acculturation factors in the National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Birth Defects Research Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology. 2009;85(7):637-646.

- ↑ 7. McLone D, Knepper P. The Cause of Chiari II Malformation: A Unified Theory. Pediatric Neurosurgery. 1989;15(1):1-12.

- ↑ 8. McDonnell G, McCann J. Issues of medical management in adults with spina bifida. Child’s Nervous System. 2000;16(4):222-227.

- ↑ 9.09.1 Campbell, SK, Linden, DW, Palisano RJ (2000). Physical Therapy for Children (2nd Edition). Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders.