Introduction

Despite recent advances in research tendinopathy rehab remains somewhat in its infancy. Our management of this condition is very different now than 10 years ago and 10 years from now will likely see different treatments again. There appears to be a bountiful supply of theoretical research but little in terms of high quality clinical trials. By this I mean that we have established a host of theories on tendon pathology, function and rehab but we have surprisingly few high quality studies proving clinically significant improvement from treatment.

Peter Malliaras et al[1] reviewed the literature recently on loading programmes for achilles and patellar tendinopathy (2 of the most common) and found a number of methodological flaws. Just 2 studies were deemed ‘high quality’, only 2 described adequate blinding and the majority did not use a validated outcome measure. They also found that around 45% of patients didn’t improve significantly with exercise programmes. So, while we can make some recommendations, there is still some way to go before we have conclusive evidence on tendinopathy rehab.

The development of a rehabilitation plan for an individual presenting with confirmed symptomatic tendinopathy requires complex clinical reasoning, with reference to the pathoanatomical diagnosis. Tendon pathology and subsequent rehabilitation will vary considerably depending on the site of pathology; stage of the tendinopathy; functional assessment; activity status of the person; contributing issues throughout the kinetic chain; comorbidities; and concurrent presentations[2].

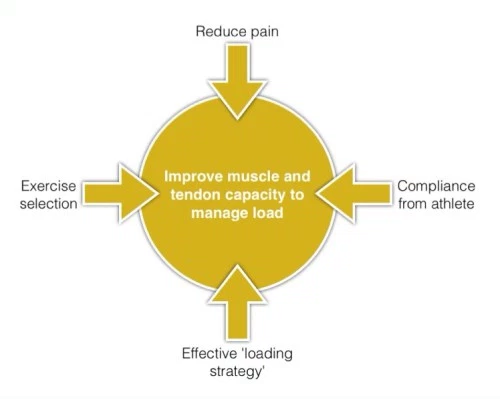

There are many treatment options for tendinopathy and many factors to consider, it can be helpful to think of what our main treatment goal is and keep this in mind. Our key goal in tendinopathy rehab is improving the capacity of the tendon and muscle to manage load. It is important to introduce Patient education and counselling as key part of our intervention. For patients with non-acute Achilles tendinopathy, clinicians should advise that complete rest is not indicated and that they should continue with their recreational activity within their pain tolerance while participating in rehabilitation. Clinicians may counsel patients with Achilles tendinopathy. Key elements of patient counselling could include[3];

- theories supporting use of physical therapy and role of mechanical loading

- modifiable risk factors, including body mass index and shoe wear

- typical time course for recovery from symptoms.

Tendon and muscle function together as a musculotendinous unit – we need to consider this in rehab, not just the tendon.[4]. Each component of the rehabilitation programme, in particular loading, must be manipulated in relation to the nature, speed and magnitude of the forces applied to the muscle/tendon/bone unit in order to achieve the goals of the particular management phase without causing an exacerbation of the pathological state or pain[2].

Rehabilitation Progression

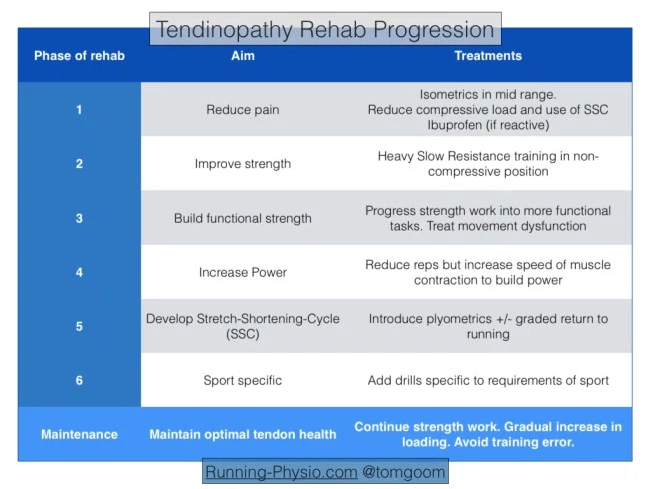

The aim of any rehabilitation strategy is to progress from pain to performance. Goon[4][5] suggests considering this in phases:

The 6 phases suggested by Goon[4][5] is combined in 4 stages by Malliaris et al. [6]

| Protocol as described by Malliaris et al. (2015) (level of evidence: 2a) [6] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Stage | Indication | Dosage |

| 1. Isometric loading | More than minimal pain during isometric exercise | 5 repetitions of 45 seconds, 2 to 3 times per day; progress to 70% maximal voluntary contraction as pain allows |

| 2. Isotonic loading | Minimal pain during isotonic exercise | 3 to 4 sets at a load of 15RM, progressing to a load of 6RM, every second day; fatiguing load |

| 3. Energy-storing loading | Adequate strength and consistent with other side and load tolerance with initial-level energy storage exercise (ie, minimal pain during exercise and pain on load tests returning to baseline within 24 hours) | Progressively develop volume and then intensity of relevant energy-storage exercise to replicate demands of sport |

| 4. Return to sport | Load tolerance to energy-storage exercise progression that replicates demands of training | Progressively add training drills, then competition, when tolerant to full training |

Phase 1 – Reduce Pain

The first aim with managing tendinopathy is often to reduce pain. It is usually the most troubling complaint for a patient and pain in the tendon can lead to reduced activity in the muscle it’s attached to. Henriksen et al[7] tested the effect of experimentally induced achilles tendon pain. They found that tendon pain causes “widespread and reduced motor responses with functional effects on the ground reaction force“.

Pain will often be more severe during a reactive tendinopathy. Typically the tendon swells in response to an increase in load. This has been described in more detail in our previous piece linked above. In short phase 1 is essentially about reducing pain in a reactive tendon (whether this is truly reactive or a reactive response on top of an underlying degenerate tendon).

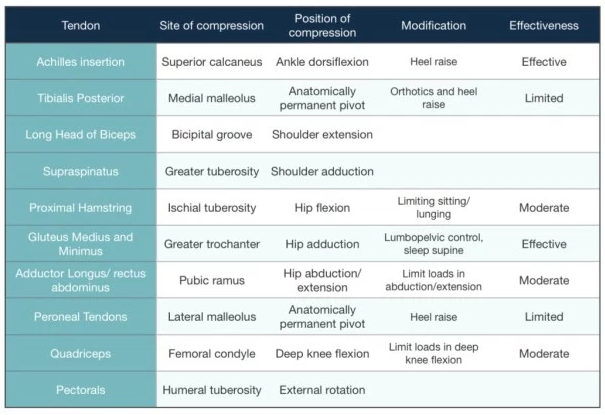

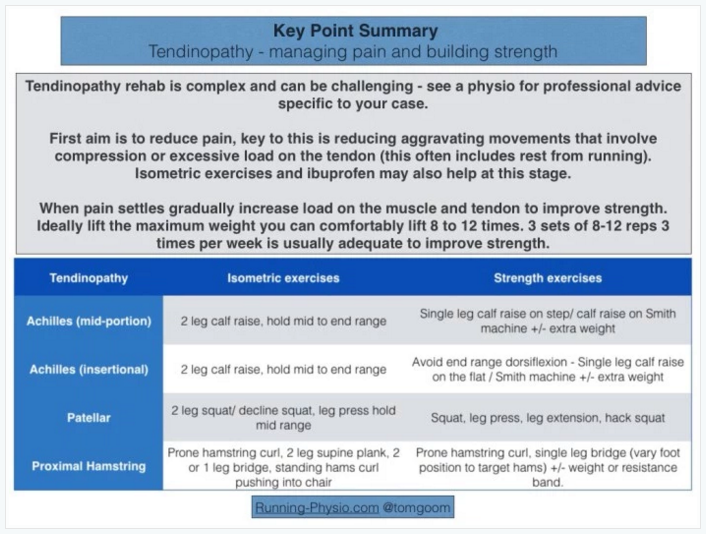

Key to reducing pain is managing the load on the tendon:

- Avoid activities that place a compressive load on the tendon, usually this is any activity that would involve stretching the effected muscle or direct tendon compression.

- Cut out activities that involve the Stretch-Shortening-Cycle (SSC) which occurs when the tendon has to behave a like a spring, stretching then shortening to store and then release energy.

- Isometric exercises can help to reduce pain[8][9]. These exercises should be done in a position where there is no tendon compression, usually in the mid-range of the muscle. They can be repeated several times a day, utilising 40-60 s holds, 4-5 times, to reduce pain and maintain some muscle capacity and tendon load. In highly irritable tendons, a bilateral exercise, shorter holding time and fewer repetitions per day may be indicated[10].

- Anti-inflammatory medications, such as ibuprofen can be used to help to reduce the reactive response.

Phase 2 – Improve Strength

Once pain has settled you can progress to phase 2 and work on strength. Strength is the ability to produce force and in this context we are aiming to improve the muscle and tendon’s ability to produce force and manage load. Muscle and tendon respond to load but it is thought that repetitive loading, such as walking or running, is unlikely to stimulate significant adaptive changes. Instead heavy load is needed to promote changes in muscle and tendon that improve their load capacity. Strength is an essential building block for muscle function, without adequate strength muscle will have poor power and endurance.

There are a number of options available to us in terms of exercise prescription, there is no recipe for this. It will depend on levels of pain and areas of weakness, patient goals and requirements of their sport. The question is how much strength is needed? In general we aim to achieve equal strength left and right and this can be measured using 10 rep max (10RM – maximum weight you can lift 10 times).

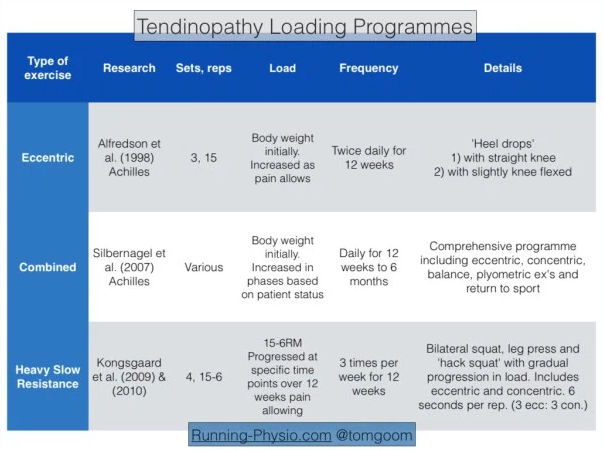

Research has focused on tendinopathy loading programmes that generally fit within 3 categories eccentric, combined or heavy slow resistance training. Goon[4] summarises the evidence for lower limb strength programmes:

For this phase of rehab you are aiming to achieve strength changes by exercising with sufficient load in a a muscle’s mid-range position. Avoid exercising with heavy loads in positions where there is likely to be tendon compression. Following research by Alfredson et al[11]. eccentric exercises have been considered the gold standard for many years. More recently research has demonstrated the importance of also including the concentric phase of exercises with heavy slow resistance training[12].

Heavy Slow Resistance training (HSR) has emerged more recently as another exercise option. Gaida and Cook[12] discuss HSR and eccentric exercise briefly in their 2011 paper on patellar tendinopathy. They note there are pros and cons of each approach; eccentric work is often prescribed as a high frequency exercise – with Alfredson’s work recommending 3 x 15 reps of 2 exercises done twice per day. HSR by contrast is usually done 2-3 times per week but in many cases will require access to gym equipment.

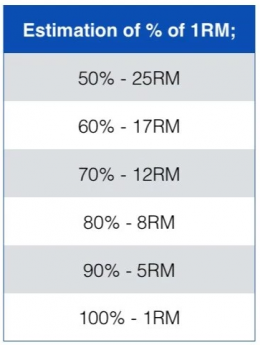

HSR involves using high loads – approx. 70-85% of 1RM (1RM – 1 repetition maximum – refers to the maximal weight you can lift once with good technique). Determining 1RM is difficult, especially in patients with pain so it can be approximated. 80% of 1RM is roughly equal to 8RM i.e. the maximal weight you can lift 8 times with good technique.

Choosing load depends on the stage and severity of your condition and how confident you are with resistance training. Those with less pain that respond well to heavy loads may start closer 8RM. Others may need to build up more gradually. Ultimately though the goal is to reach these higher loads to create optimal tendon adaptation and muscle strength changes. The ACSM guidelines[13] recommend working at between 8 and 12RM when starting strength work, although there is some debate on exact parameters and this is based on research on a health population not those with tendinopathy. They suggest 3 sets of 8-12 reps separated by 2-3 minute rest periods, repeated 2-3 times per week. Kongsgaard et al[14][15] used a graduated approach starting with lower loads at 15RM and building up to 6RM over 9-12 weeks providing there was no significant increase in pain. They used the squat, leg press and ‘hack squat’ and recommended 4 sets of each exercise with a 2-3 minute rest between sets, repeating 3 times per week.

A third option with strength work is the combined approach of Silbernagel et al[16]. They used rehabilitation phases and progressed patients depending on their symptoms. They also encouraged a monitored return to sport. Silbernagel et al. don’t describe a specific amount of load in terms of % of 1RM, instead they start with the resistance of body weight (for calf raises) and progress in a similar manner to Alfredson – using a back pack or weights machine to increase load. There are however several key differences. Silbernagel et al. include both the concentric and eccentric component of the exercise and progress to include power and plyometric exercises. As such the findings from Silbernagel apply across most of the rehabilitation phases, not just strength.

Malliaras et al[1] reviewed the literature on achilles and patellar tendinopathy. They found that HSR training was more likely to lead to tendon adaptation but required further research. They didn’t find evidence to support isolating the eccentric component (as in Alfredson) although they did acknowledge that several potential mechanisms, such as neural adaptations, had not been investigated. Overall Malliaras et al[1] found combined and eccentric as well as HSR loading had the highest level of evidence for improving neuromuscular function.

There are a host of variables that can be modified to tailor strength work to an individuals needs and to have specific effects on the musculotendinous unit. These include time under tension, speed of contraction, position of limbs during exercise, range of movement covered, rest between sets and scheduling of exercise sessions. For example increasing time under tension during heavy slow loading may increase strain on the tendon and result in greater adaptation, however increasing speed will be more likely to improve power and prepare for activities involving the Stretch Shortening Cycle. Changing limb position during exercise (e.g. Foot position with squat) will vary the direction of the load and is useful to consider as people move in multiple directions so will encounter varying loads.

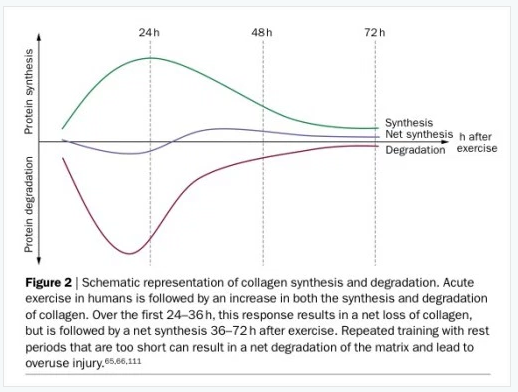

On a practical note it is worth remembering that tendon response to load takes time, consider both short term and long term reaction to load. In the short term there will be a net loss of collagen production for around 24-36 hours post exercise – so allow adequate rest days between strength sessions.

In the longer term consider that significant changes in muscle strength take 6-8 weeks and tendons change slowly so may take 3-4 months to respond to a loading programme. All the studies mentioned above included at least 12 weeks of rehab – there’s no quick fix!

Phase 2 summary – tendinopathy is likely to result in reduced muscle strength and function. Restoring this is essential for the long term health of the tendon. Several strengthening options exist but all share a common goal – gradually increase the load on the muscle and tendon while carefully monitoring pain. Strength work should be done in mid-range positions to avoid tendon compression. Ideally for optimum strength changes the load should be sufficient that your patient can only manage around 8-12 reps (i.e. 8-12RM) you may need to build up for this as pain allows.

Phase 3 – Functional Rehabilitation

For many reducing pain and building strength combined with a gradual return to usual activities will be enough to rehabilitate a tendinopathy. If this is combined with ongoing strength work to maintain tendon load capacity and a sensible training schedule then risk of recurrence will be fairly low. However for some with more severe or persistent tendinopathy or those whose sport requires a high level of loading then progression through the phases to including functional rehabilitation is recommended.

Prior to starting functional rehab pain must be well managed and there must be adequate basic strength. As a rough guide 10 rep max should be equal left and right for the muscle involved.

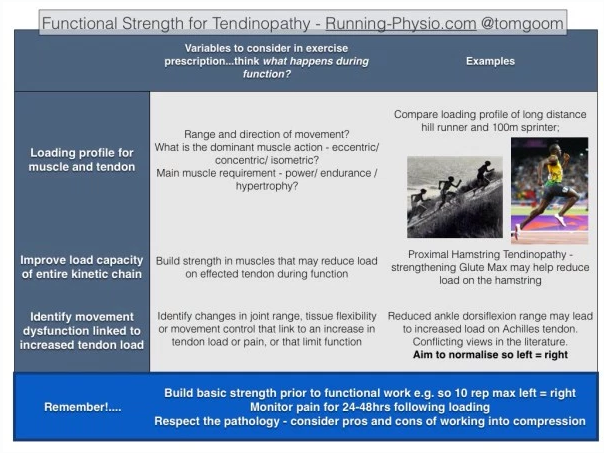

For every athlete, there will be a specific amount and type of load the tissues will have to cope with. When building functional strength we must consider what activities our patients are working toward and adapt the functional strength and conditioning to suit. It can help to think of functional rehab in 3 broad categories:

- exercise specific to the functional requirements of the effected muscle and tendon,

- improving the load capacity of the entire ‘kinetic chain’,

- and addressing movement dysfunction that links to the tendinopathy.

Functional rehab for muscle and tendon

For this we must think more broadly in terms of muscle function and change position, reps, sets. This involves working out how the muscle is working and in what positions through the activity, then adapting exercises to be performed in these situations. Also think about the strength-endurance demands on the muscle and consider changing load and reps to match.

Strengthening the entire kinetic chain

By ‘kinetic chain’ we mean the rest of the body that’s involved in a function. If we strengthen other muscles involved in this process we should, in theory, be able to reduce some of the load on the effected muscle and tendon. In doing so we can also improve economy and performance. For example in a trail runner with achilles tendinopathy we would also look at how the gluts and hamstrings are performing to optimise uphill running.

Addressing movement dysfunction

Movement dysfunction is a complex. It covers a number of factors including strength, joint range of movement, tissue flexibility, movement control and biomechanics. There is a huge amount of variety in what is ‘normal’ and some debate about what aspects of movement we should change or even if we can actually change some of these aspects. Load is such a key area in development of tendinopathy it is perhaps more likely that it is extrinsic factors such as training volume and intensity that are more relevant than intrinsic factors such as biomechanics. Like many aspects of patient care it comes down to assessing the individual and reasoning how each factor is linked and what is key. In terms of movement dysfunction look for differences between the symptomatic and asymptomatic side and see if they link with the pathology. Also aim to restore enough range and control of movement for function.

If we really want to replicate function why not just do our usual sport?

Silbernagel et al[16] demonstrated that there are specific benefits associated with continuing sport as part of your rehab as long as pain is closely monitored. For example, running is likely to have benefits on cardiovascular fitness but is less likely to be as effective in building strength or improving tendon load capacity. In addition running activates the tendon’s Stretch-Shortening-Cycle which requires adequate muscle strength to avoid excessive load on the tendon. The difference between functional rehab and just doing your sport comes down to the type of loading and how the muscle and tendon respond to it. A graded return to sport is a valuable part of tendon rehab but it isn’t a replacement for appropriate strength work.

In summary

Functional rehab can be a complex area and requires an individualised assessment of the individual. Exercises should be designed to improve the load capacity of the effected tendon and muscle during function as well as the rest of the kinetic chain. Identifying relevant movement dysfunction can be challenging but should involve assessment of joint range of movement, tissue flexibility, control of movement and biomechanics. These areas should be addressed while respecting the pathology involved and monitoring pain in response to loading. Exercises in positions with tendon compression should be use with caution.

Return to sport [6][4][5]

The following should be done to progress from stage 3 on move towards Return to Sport:

- Increase in power: by reducing the repetitions but increasing the speed of the muscle contraction to build power

- Develop Stretch-Shortening-Cycle (SSC): by introducing plyometrics and graded return to running

- Load tolerance to energy-storage exercises by adding progression to will replicate the demand placed on the tendon by training

- Add training drills specific to the sport

- Competition when the patient is tolerant to full training

Tendon neuroplastic training[17]

Rio et al found that current rehabilitation uses self-paced strength training (for e.g. a patient does 3×10 contractions lifting a weight – without any external cues/advice on timing). This type of training may lead to recurrence of tendinopathy, as it does not address motor control sufficiently and thus does not change the corticospinal drive to the muscle.

Externally paced training would be when the patient contract the muscle, concentrically and eccentrically on auditory (like using a metronome) or on visual cues. Externally paced strength training was shown to alter tendon pain and corticospinal control of the muscle.

Tendon neuroplastic training uses strength-based training with external cues as a strategy to optimise neuroplasticity. This was shown effective with patellar tendinopathy and further research is required into other tendinopathies.

Resources

Click on References

Ola!

Como podemos ajudar?