Definition/description

Sacroiliac joint syndrome is a significant source of pain in 15% to 30% of mechanical low back pain sufferers. The posterior sacral ramus of the spinal nerve is the main nerve that innervates the sacroiliac joint.[1] Mechanical dysfunction of the sacroiliac joint results in more pain and decreased mobility. The symptoms are often described as pain over the posterior aspect of the joint. The pain varies in its degree of severity; it can be referred to the groin, over the greater trochanter, down the back of the thigh to the knee, and sometimes down the lateral or posterior calf to the ankle, foot and toes.[2] Sacroiliac joint syndrome occurs when the sacroiliac ligaments are damaged or torn by age causing too much play in the joints.[3] This causes an inflammation of the joint making it possible to disrupt. Degenerative changes need to be considered as well. Traumatic incidents such as motor vehicle accidents, falls landing on the buttocks, and cumulative injuries, such as lifting and running, are the most common causes.[4] It occurs more frequently in older people, but there is too little research done to substantiate this conclusion.

Sacroiliac Joint Syndrome is a condition that is difficult to diagnose and is often overlooked by physicians and physiotherapists.[5]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

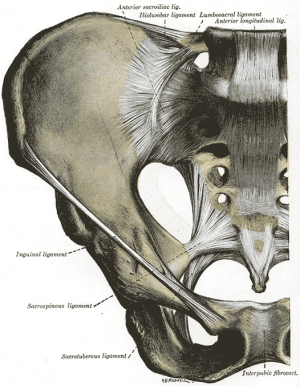

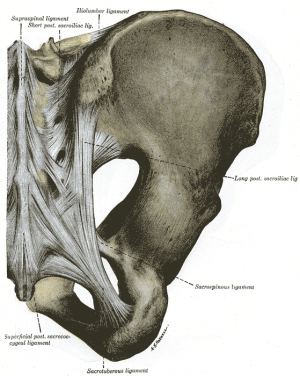

The sacroiliac joints are located on each side of the spine between the two pelvic bones, which attach to the sacrum.[6]

Multiple structures are involved in the support and movement of the sacroiliac joints.[7] The ligaments which contribute to this synovial joint are the anterior and posterior sacroiliac ligament, interosseus ligament, sacrotuberous ligament, sacrospinous ligament and iliolumbar ligament.[5] The joints are surrounded by some of the most powerful muscles of the body, but none of these have direct influence on joint motion.[8]

The main function within the pelvic girdle is to provide shock absorption for the spine and to transmit forces between the upper body and the lower limbs.[9]

Epidemiology/Etiology

It is often hard to determine exactly what caused the wear and tear to the joints. One of the most common causes of problems at the Sacroiliac joint is a trauma. The force from these kind of injuries can strain the ligaments around the joint. Tearing of these ligaments leads to too much motion in the joint and over time it will lead to degenerative arthritis.

Pain can also be caused by an abnormality of the sacrum bone, which can be seen on X-rays.

Pregnant women have a greater chance to develop sacroiliac joint syndrome. Female hormones are released during pregnancy, relaxing the sacroiliac ligaments. This stretching in ligaments results in changes to the sacroiliac joints, making them hypermobile.[9]

Clinical Presentation

Symptoms of sacroiliac joint syndrome are often difficult to distinguish from other types of low back pain. This is why making a diagnosis of sacroiliac joint syndrome is very difficult. The most common symptoms include:[9]

- Low back pain

- Buttock pain

- Thigh pain

- Difficulty sitting in one place for too long due to pain

- Local tenderness of the posterior aspect of the sacroiliac joint (near the PSIS)[10] (level of evidence B)

– Pain occurs when the joint is mechanically stressed

- Forward bending causes also pain

- Absence of neurological deficit

- Absence of nerve root tension signs

- Aberrant sacroiliac movement pattern[11]

Differential Diagnosis

Sacroiliac joint syndrome is a controversial diagnosis, therefore pain and injury to the sacroiliac joint is commonly overlooked.[12] This condition is often listed under the general term dysfunction, a term that serves as a collective term for different conditions. The differential diagnosis should include:

Important to note: the sacroiliac joint syndrome is not a synonym of sacroiilitis!

Diagnostic Procedures

Physiotherapists use a variety of orthopedic provocation tests. The diagnosis can be conclusive if at least one of these tests is positive. Besides the known provocation tests: Gaenslen Test, Sacral Thrust Test, Thigh Thrust test, Compression test and Distraction Test[14], there are also the Yeoman’s test, Faber test (Patrick Sign), Gillet test, Laguerre test and the Sacroiliac Stress Test; described below.

- Yeoman’s test: The patient is prone with the knee flexed 90°. The examiner raises the flexed leg off the examining table, hyperextending the hip. This test places stress on the posterior structures and anterior sacroiliac ligaments. Pain suggests a positive test.[15]

- Gillet test:[16] The examiner’s thumbs are placed under the posterior superior iliac spine and S2. The patient is asked to stand on one leg while moving the opposite leg towards the chest. If the joint side that is flexed moves up, this is considered a positive test.[7]

- Laguerre test:[7] The patient lies supine and the examiner flexes, abducts and rotates the patients affected joint. The pelvis must be stabilized and pain signifies a positive test. This test differentiates hip pain from sacroiliac pain.

- Sacroiliac Stress Test:[15] The patient lies supine. The examiner exerts anterior pressure on the iliac wings with both hands. By crossing his or her hands, the examiner adds a lateral force to the compression. Pain is a sign of strained anterior sacroiliac ligaments.

CT and MRI are often used to confirm the diagnosis.

Examination

Physical Therapy Management

In the first stage of the treatment the aim is to reduce the inflammation with icepacks and anti-inflammatory medication. A second important goal is to improve mobility using mobilizations, manipulation or exercise therapy. If there are complaints of instability, it can be useful to make use of a sacroiliac belt to temporarily support the pelvis, together with progressive stabilization training to increase motor control and stability. If the sacroiliac joint is severely inflamed, a sacroiliac belt can also be used. Finally, postural and ergonomic advice will help the patient to decrease the risk of reinjury.[17][18]

Core Stability

Exercises is a major component of a programme when treating Sacroiliac pain and core stability has been shown to be effective.

Stabilization Exercises.

For the lumbar exercises, awareness is necessary in order to isolate the co-contraction of the local muscle system, which happens without global muscle substitution. It’s necessary to train the specific isometric co-contraction of two important core stabilizers: musculus transversus abdominis and the lumbar multifidi. These muscles have to be trained at low levels of maximal voluntary contraction; it’s important to maintain controlled respiration and neutral lordosis in weight bearing exercises.[19] It’s really important to take into account the following principles: breathe in and out, tighten the lower abdomen below the umbilicus carefully and slowly without moving the upper stomach, back or pelvis such as a hollowing. Furthermore, a bulging of the multifidus muscle may be felt by the physiotherapist. There is a need of precise palpation of the muscles to ensure effective muscle activation.[20]

Isolated Lumbar Stabilizing Muscle Training.

Specifically for stabilization exercises, it’s recommended to begin in a quadruped position. The physiotherapist can manually guide the spine through the full arc of flexion and extension. It’s essential to tuck in the chin and hollow the abdomen by tilting the pelvis posteriorly. Lift one arm slowly while continuing to maintain the neutral position of the spine, without changing the natural curves; return the arm and then continue with the other.

The lumbar multifidi can be palpated medial to the lumbar facet joints bilaterally; this allows the physiotherapist to avoid changes in muscle activity of the long spinal extensor muscles, ensuring that the patient is performing the exercise correctly.

Activation of the musculus transversus abdominis and multifidus together in sitting and standing positions, or while performing stepping and balance activities are essential[20][21]

Integration of Lumbar Stabilization into Light Dynamic Functional Tasks

Sit on an unstable base of support and co-contract the transverse abdominis and multifidus muscles while performing the following stabilizing exercises individually to improve lumbopelvic control: hip extension, lumbar spine extension, and thoracic spine extension with co-contractions. These co-contractions can also be performed while walking and performing other activities of daily living. [21]

Integration of Lumbar Stabilization into Heavy-Load Dynamic Functional Tasks

The next exercises are isometric co-contractions to be performed with the addition of heavier external loads to the lumbar spine: bridging and single-leg extension in quadruped.

Single-leg extension from quadruped can provide further challenge with alternating arm/leg extensions.

To increase the complexity and the load of these exercises, single-leg bridging and the bilateral bridging exercises can be performed with the lower extremities on an unstable base of support such as a Swiss ball.

Finally an example of an exercise to improve coordination is single-leg bridging with alternating lower extremities on an unstable base of support. Alternating the stabilizing lower extremity on the Swiss ball further challenges coordination and balance while improving the stabilization capabilities of the core musculature.

During all these exercises the co-contraction of the musculus transversus abdominus and multifidi are imperative.[21]

Manipulation

Treatment of Sacroiliac Joint (SIJ) Syndrome is best approached from a multidisciplinary standpoint and it is not uncommon to see modalities such as manipulation included in the programme. Conservative treatment consists of exercise therapy and manual therapy. It’s important to determine and address the underlying causes of dysfunction during the treatment.[22]

There is evidence for both SIJ manipulation and lumbar manipulation. Following the performance of each of these manual therapy techniques pain and functional disability are significantly improved in patients diagnosed with SIJ syndrome. Manual spinal thrust manipulation may be considered as a component of effective treatment for patients with SIJ syndrome.[23]

SIJ Manipulation

The patient lies on his back with the therapist standing opposite the side to be manipulated. The patient places his hands behind his head and the therapist then moves the patient passively into side bending to end range toward the target side. The therapist then delivers a quick thrust to the Anterior Superior Iliac Spine (ASIS) in a posterior and inferior direction (Cleland et al., 2006; Edmond, 2006).[23]

Lumbar Rotational Manipulation

The patient lies on the unaffected side and the therapist stands opposite the patient, flexing the patient’s hip until the lumbar spine is in flexion. The therapist grasps the patient’s lower shoulder and arm to stabilize him, and moves him into left trunk side bending and right rotation, until motion is felt at the desired segment of the lumbar spine. The arms of the patient are placed above the therapist’s arm. This position is maintained while the patient is rolled toward the therapist. The therapist’s other arm is used to apply a high-velocity low-amplitude thrust to the pelvis in an anterior direction (Cleland et al., 2006).[23]

Posterior Iliac Rotation Sacroiliac Joint Manipulation

The purpose of this technique is to manipulate an iliac anterior rotation displacement sacroiliac joint dysfunction and to restore posterior rotation of the ilium. The patient lies on his side and toward the therapist. The therapist places his hand on the ASIS and the other is on the ischial tuberosity. The top hip is flexed to 90° and the other leg is relatively extended. Rotate the spine to the level of the L5-S1 segment pull the patient’s bottom arm in an anterior and superior rotation. The hand on the ASIS pushes posteriorly and the other pushes anteriorly. This must be maintained for 10 to 30 seconds.[24]

Anterior Iliac Rotation Sacroiliac Joint Manipulation

The aim is to manipulate a posterior iliac rotation displacement to restore anterior rotation of the ilium. The patient lies prone with a pillow under his pelvis. The therapist supports the thigh just above the knee. To stabilize the ilium, the other hand is on the ipsilateral PSIS (Posterior Superior Iliac Spine) pushing in an anterolateral direction. The therapist’s fingers should point toward the patient’s feet. After positioning, the therapist brings the leg above the table into hip extension just enough to take up the slack in the hip flexors. It is recommended to hold this position for 10 seconds with the knee either extended or flexed.[24]

Stabilisation

Pelvic Belt

The tension of a pelvic belt is comparable to the muscle activity of the transversus abdominis (and the obliquus internus abdominis) muscle. Transversus abominis has an anterior attachment on the iliac crest, an ideal place to act on the ilium producing compression of the SIJ in combination with stiff dorsal sacroiliac ligaments.

A minimum contraction of 30-40% of the maximum voluntary force of the transversus abdominis is sufficient to achieve stability of the pelvis according to Richardson et al. No greater contraction is needed to achieve joint stabilization because the lever arm of the transversus abdominis is almost equal to the lever arm of the pelvic belt. There is also no significant change of stability by increasing belt tension from 50 to 100 N, but if the belt is placed in too low of a position, it may lead to a small decrease of laxity. Greater belt tension isn’t recommended secondary to the potential of skin pressure and discomfort.

When the pelvic belt is worn there is a decrease of the sacroiliac joint laxity. This difference in laxity is due to the position of the belt. Positioning the pelvic belt just below the anterior superior iliac spines (the high position) is more effective than the low position (at the top of the pubic symphysis). However, the tension of the belt has no significant influence on the stability of the SI-joint. [25]

Sacroiliac Binder

When the use of the sacroiliac belt for a hypermobile SI-joint is appropriate, it should be worn for 24 hours per day up to 6 to 12 weeks. This belt should be used in combination with physical exercises and manual therapy in the case of joint dysfunction and muscle imbalance. The belt may be removed once the patient has improved control of the lumbopelvic musculature. The location of the sacroiliac belt should be at the superior aspect of the PSIS to assist in stabilizing and supporting the pelvis.[26]

Key Research

- Kamali, F., Shokri, E., The effect of two manipulative therapy techniques and their outcome in patients with sacroiliac joint syndrome. Journal of Bodywork & Movement Therapies, 2011.

Sacroiliac joint and lumbar manipulation was more effective for improving functional disability than Sacroiliac joint manipulation alone in patients with Sacroiliac Joint Syndrome. Spinal high-velocity low-amplitude manipulation may be a beneficial addition to treatment for patients with SIJ syndrome.

- SLIPMAN W.C. Sacroiliac Joint Syndrome. Pain Physician. Vol. 4, N° 2, p 143-152, 2001. ISSN 1533-3159

History and physical examination can enter Sacroiliac Joint Syndrome into the differential diagnosis, but cannot make a definitive diagnosis of Sacroiliac Joint Syndrome. Treatment options for Sacroiliac Joint Syndrome include physical therapy, orthotics and manipulation.

It is important to notice that there is only a small amount of research available about the Sacroiliac Joint Syndrome. Further research will be a great contribution.

Clinical Bottom Line

A Sacroiliac Joint Syndrome is a condition that is often overlooked by physiotherapists. It is often listed under the general term “dysfunction”, but this syndrome has to be differentiated from other sacroiliac joint disorders. To get a clear view of the Sacroiliac Joint Syndrome, further research has to be done in the future.