Although not clearly defined, Second Impact Syndrome (SIS) most commonly describes the occurrence of rapid cerebral edema after a second head injury that is sustained while an individual is still recovering from symptoms caused by a prior concussion. [1][2] [3] It has also been suggested that indirect head injuries, for example caused by trauma to the chest which can transfer forces to the head, can cause SIS. [4] It is controversial whether or not SIS truly exists, in part due to its ambiguous definition and lack of supporting evidence. Further investigation is necessary in order to better understand SIS as it is difficult to differentiate the impact of the subsequent injury from the primary injury and determine which factors are responsible for the fatal effects that occur with SIS. [5] Due to lack of characterization, SIS is not currently recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) and does not have its own unique ICD-10 code. [2] While the reality of SIS is uncertain and occurrence is very rare, recognition of the potential condition is important as it has shown to be associated with mortality and morbidity rates ranging from 50-100%. [2][3]

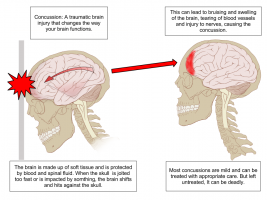

While the pathophysiology of SIS is not fully understood, theories suggest that dysautoregulation of the blood vessels that supply the brain is responsible for the substantial cerebral swelling that occurs. [4][6] It has been proposed that during the primary concussion, cerebral edema is controlled by autoregulation which limits blood flow to the brain. [4][6] Concussion is believed to alter cerebral metabolism, reducing the ability of the brain to respond appropriately to the stress incurred by subsequent concussions. [4][6] Hence, there is a window of vulnerability for approximately 10-15 days after an initial head injury. [4][5] The rapid increase in intracranial pressure may lead to herniation and compression of the brainstem, causing dilation of the pupils, respiratory failure and potentially death within minutes. [4][6]

With SIS, the events that occur after a second impact may start with the athlete appearing stunned with no loss of consciousness. [2][4] The athlete is often able to get up and stay on his or her feet long enough to walk off the field, then within seconds to minutes will collapse into a semi-comatose state during which rapid dilation of the pupils may occur and possible respiratory failure. [2][4] Other signs and symptoms may include seizures, vomiting and headache. [2]

Neuroimaging Findings [2]

- Cerebral swelling

- Midline brain herniation

- Potential acute subdural hematoma

Associated Conditions [2]

- Concussion – initial injury caused by single head trauma

- Post-concussion syndrome – post-concussive symptoms that can last weeks to years after initial concussion

- Malignant brain edema – can follow an initial head injury. With SIS, brain edema can occur with forces less than would typically be needed to cause such injury with initial head trauma

Risk Factors

- Children, adolescents, and young adult – possibly due to increased risk taking behaviours or underdevelopment of the brain [2][5]

- Male gender – perhaps due to genetics or higher rate of participation in sports with the highest risk of SIS [2]

- Athletes in certain contact sports; American football, boxing, rugby, karate [2][3][4][5]

- Post-concussive symptoms [5]

See Concussion and Post-concussive syndrome to determine when an athlete is symptom-free and able to return to play in order to reduce the risk of SIS.

As SIS generally results in fatality within minutes, treatment options are currently very limited. [6] In the event that the athlete is able to receive medical attention, management revolves around stabilizing the athlete, controlling intracranial pressure and maintaining respiratory function. [6]

As there is no consensus on evidence-based guidelines regarding timing and level of participation to prevent SIS when considering return to play, the following tips are suggested to reduce the risk of occurrence:

- Restrict return to play if athlete demonstrates signs or symptoms of concussion

- Observe athletes closely after initial head injury

- Ensure appropriate follow-up with neurosurgeon or physician experienced in concussion after initial head injury and before return to play

- ↑ Saunders RL, Harbaugh RE. Second impact in catastrophic contact-sports head trauma. JAMA. 1984;252(4):538-539.

- ↑ 2.002.012.022.032.042.052.062.072.082.092.10 Hebert O, Schlueter K, Hornsby M, Van Gorder S, Snodgrass S, Cook C. The diagnostic credibility of second impact syndrome: A systematic literature review. J Sci Med Sport. 2016;19:789-794. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2015.12.517.

- ↑ 3.03.13.2 Stovitz SD, Weseman JD, Hooks MC, Schmidt RJ, Koffel JB, Patricios JS. What definition is used to describe second impact syndrome in sports? A systematic and critical review. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2017;16(1):50-55.

- ↑ 4.04.14.24.34.44.54.64.74.8 Cantu RC. Dysautoregulation/second-impact syndrome with recurrent athletic head injury. World Neurosurg. 2016;95:601-602. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2016.04.056.

- ↑ 5.05.15.25.35.4 McCrory P, Davis G, Makdissi M. Second impact syndrome or cerebral swelling after sporting head injury. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2012;11(1):21-23.

- ↑ 6.06.16.26.36.46.56.6 Quintana LM. Second impact syndrome in sports. World Neurosurg. 2016;91:647-649. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2016.04.035.

- ↑ Brainline. Second Impact Syndrome. Available from: ↑ Brainline. The Science Behind Second Impact Syndrome and Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. Available from: function gtElInit() { var lib = new google.translate.TranslateService(); lib.setCheckVisibility(false); lib.translatePage('en', 'pt', function (progress, done, error) { if (progress == 100 || done || error) { document.getElementById("gt-dt-spinner").style.display = "none"; } }); }

Ola!

Como podemos ajudar?