Introduction

Suctioning is ‘the mechanical aspiration of pulmonary secretions from a patient with an artificial airway in place’. The procedure involves patient preparation, the suctioning event(s) and follow-up care[1].

Suction is used to clear retained or excessive lower respiratory tract secretions in patients who are unable to do so effectively for themselves[2]. This could be due to the presence of an artificial airway, such as an endotracheal or tracheostomy tube, or in patients who have a poor cough due to an array of reasons such as excessive sedation or neurological involvement[3].

Having an artificial airway in situ impairs the cough reflex and may increase mucus production[4]. Therefore, in the neonatal and paediatric ICU, suctioning of an artificial airway is likely to be the most common procedure[5][6].

Oropharangeal and nasopharangeal suction is a technique intended to stimulate a cough to remove excess secretions and/or aspirate secretions from the airways that cannot be removed from a patient’s own spontaneous effort[2]. A cough may be stimulated by a catheter in the pharynx (oropharangeal suction) or by passing a catheter between the vocal cords and into the trachea to stimulate a cough (nasopharangeal suction). The trachea is accessed by insertion of a suction catheter either via the nasal passage and pharynx (nasotracheal suction) or via the oral cavity and pharynx (orotracheal suction) using an airway adjunct. Nasotracheal suction may be undertaken directly via the nostril without an airway adjunct. However, in some situations, where repeated suction is anticipated and therefore a nasopharyngeal airway should be utilised. Secretions are removed by the application of sub-atmospheric pressure via wall mounted suction apparatus or portable suction unit[6].

Terminology

- Airway Suction: The removal of airway secretions/foreign material by artificial means, using an applied negative pressure

- Yankauer Suction Catheter: A rigid suction tip used to aspirate secretions from the oropharynx

- Oropharyngeal Suction: (OP) requires the use of an airway adjunct (Guedel Airway)

- NasopharyngealSuction: (NP) may be undertaken directly via the nostril without an airway adjunct. If repeated suction is anticipated a nasopharyngeal airway should be utilised. This is inserted only by those that are trained to do so.

- Suction is an invasive procedure and should NOT be carried out on a routine basis. But, suctioning is an integral part of the management of intubated/ventilated patients.[2][7]

Two Systems Used:

-

Closed Suction System

- Do not disconnect from ventilator. Similar procedure to open technique but no application of sterile glove

- Enables a clinician to clear the lungs of secretions whilst maintaining ventilation and minimising contamination with the least possible disruption to the patient

- Helpful in preventing cross contamination and infection[8]

-

Open Sterile Technique–

- Clearing the airways of a mechanically ventilated patient with a suction catheter inserted into the endotracheal tube after the patient has been disconnected from the ventilator circuit.[9]

A Cochrane review that included results from 16 trials concluded that suctioning with either closed or open tracheal suction systems did not have an effect on the risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia or mortality. They reported that more studies of higher methodological quality are required, particularly to clarify the benefits and hazards of the closed tracheal suction system for different modes of ventilation and in different types of patients[10].

Airway Suction via Nasopharyngeal and Oropharyngeal Airways

Oropharyngeal (OPA) and Nasopharyngeal Airways (NPA) can be used to:

- Restore airway patency by separating the tongue from the posterior pharyngeal wall

- Help maintain adequate oxygenation through providing an avenue for adequate ventilation

- Provide access for the removal of secretions in the upper airway via suctioning.

The insertion of an NPA or OPA is indicated for secretion removal in patients who have evidence of secretions in their upper airway but have an absent cough reflex or an impaired, ineffective cough. This often reflects patients who have an altered conscious state, are weak, or neurologically impaired.[11]

Indications that secretions are present in the upper airway that may be accessible via suction include:

- Audible, upper airway transmitted sounds

- Muffling of a patient’s voice by secretions

- Transmitted sounds on auscultation of the chest wall

- Tactile fremitus

- Moist, rattling cough[2]

When these signs are present and the patient is unable to clear secretions via a voluntary, stimulated, or assisted cough – or by other means (e.g. physiotherapy techniques), suction may be indicated.[11]

Stimulating a Cough

During an assisted cough the physiotherapist applies pressure to the chest wall in synchrony with a patient’s cough in order to increase the PEFR achieved. Two common methods include

- An inwards pressure applied to the lower lateral rib

- An A-P pressure applied to the upper anterior chest wall.

If a patient does not have a strong, effective, spontaneous cough, several methods can be used to try and stimulate a stronger cough. These include a tracheal rub and catheter stimulation in the oropharynx.[12]

- Tracheal rub

The physiotherapist uses a finger or thumb to rub using blunt pressure across the trachea above the supra-sternal notch. (i.e. a flat finger/thumb is used, not pointed)

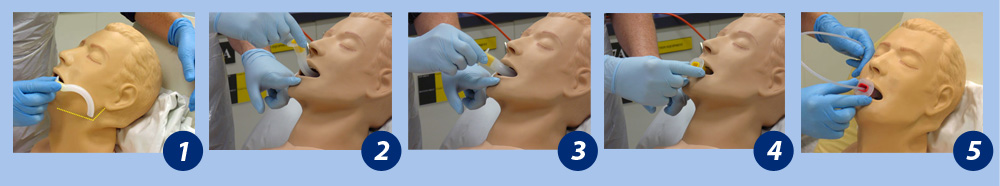

2. Catheter stimulation of a cough

A cough can be stimulated by inserting the tip of a catheter (FG 10 or 12) along the outside of the teeth and around in to the back of the oropharynx. As the catheter is passed along the side of the teeth, a block is commonly felt when the catheter comes in contact with the mandible. Rotating the catheter gently will allow the catheter to move off the mandible and in to the back of the oropharynx where a cough may be stimulated and/or secretions suctioned.

Avoid passing the catheter directly over the tongue, as this can stimulate the gag reflex.

If successful, this technique may prevent the need for suctioning via the nasopharynx or with a Guedel airway. It may also provide information on a patient’s tolerance of oropharyngeal stimulation (e.g. stimulation of biting reflexes, gag reflexes) which may bias selection of nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal airway insertion if required.[11]

Oropharyngeal Suction

Oropharyngeal (OPA) or “Guedels” Airways

An OPA is a rigid PVC tube that is flanged at the proximal (mouth) end and is shaped to conform to the curvature of the palate. When inserted properly, the flange sits just outside the lips and the tube keeps the patient’s tongue extended and prevents it from opposing against the posterior pharynx.

Choosing the Correct OPA Size

OPAs are made in various sizes. The correct size OPA should track from the corner of the patient’s mouth to the angle of the jaw. Insertion of an OPA of incorrect size may push the tongue back toward the pharynx creating an obstruction.

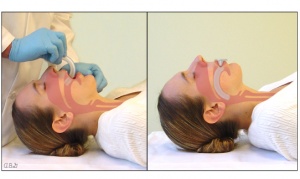

OPA insertion

Suction the oropharynx and inspect it for possible obstructions e.g. food, tumours, and dentition e.g. false teeth. Select a size ten or twelve suction catheter. Lubricate the tip of the catheter and insert the catheter into the OPA prior to insertion into the patient’s oropharynx (this step is optional but can speed up the process). Ensure the catheter moves easily through the OPA orifice and position its tip to protrude just beyond the end of the OPA.

Initially, the airway goes in upside down, with the distal end pointing towards the roof of the mouth or sideways. This prevents pushing the tongue back into the oropharynx during insertion. When the airway reaches the back of the throat, rotate it so that the curved part fits over the tongue. Proceed with airway suction. If the gag reflex is stimulated and the patient vomits, be prepared to suction the patient’s mouth with a Yankauer, and turn them onto their side if necessary.[11]

Duration of use

When suctioning via an OPA, the OPA is usually removed when the suctioning is complete.

Sequence showing correct insertion of an OPA

Nasopharyngeal airways

Suction via the nasopharynx can be performed with or without the use of a nasopharyngeal airway (NPA). Use of an NPA may be preferable in patients who have evidence of secretion retention, and where the quantity of secretions would require frequent suctioning to be performed.[13]

The NPA is a robust, supple but kink-resistant tube made of soft rubber. They are flanged at the proximal (nasal) end. When properly placed, the tip rests behind the tongue, just above the epiglottis, having separated the soft palate from the posterior wall of the oropharynx. A suction catheter can be passed through the tube and into the posterior pharynx and trachea.

The NPA has some advantages over the OPA, they include:

- an NPA does not stimulate a patient’s gag reflex

- an NPA is better tolerated than an OPA in conscious patients

- an NPA can often be left in situ for longer periods than an OPA

- even while the NPA is in situ, a patient is still able to speak

- it can be used when access to the mouth is technically difficult (trismus, convulsions).[11]

Choosing the Correct NPA Size

NPAs are available in a variety of sizes, with variation in both the internal diameters of the airway, and in length.[13]

Research Support

Research has validated that when sizing an NPA for a patient:

- the length of the NPA is more critical than its diameter

- ideal NPA length is best judged by considering the patient’s height and gender

- estimating NPA length by measuring the distance from the tip of the nose to the tragus of the ear has not been validated in adults. A study in Chinese children found a close association between nares-vocal cord distance and nose tip-earlobe distance, with the ideal NPA length being slightly less than this anthropometric measurement[3].

Duration of Use

There is no clear evidence for the ideal duration of NPA placement. General consensus indicates that if clinically indicated, they can remain in place for up to 24 hours. However, to prevent pressure areas, switching the NPA from one to the other nostril every six to eight hours is recommended. The nose should be inspected regularly for pressure areas around the flange of the NPA.

If a patient requires suctioning relatively infrequently e.g. one to four times a day after physiotherapy treatment, then re-inserting the airway before each suction procedure or performing suction without the NPA may be appropriate.

If the patient has copious pulmonary secretions requiring suction every hour or twice hourly, then inserting an NPA and leaving it in situ is warranted to permit easy access and to minimise trauma to the nasal mucosa from repeated insertion of the suction catheter.[11]

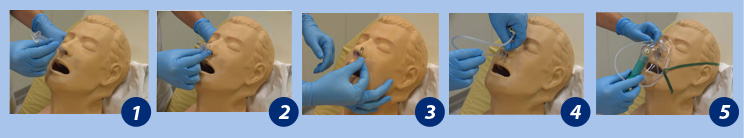

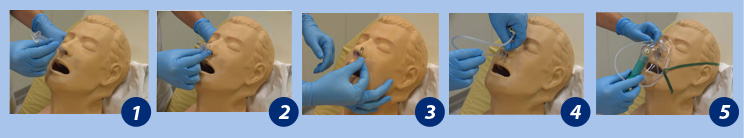

Insertion

Suction the oropharynx and inspect it for obstructions e.g. food, tumours, and dentition e.g. false teeth. Inspect the nose to exclude obvious nasal polyps or septal deviation in either nostril. Determine the length of the NPA to use based on the patient’s gender, height and/or nose-eartip.

Before inserting the NPA, place a large safety pin through the shorter edge of the rubber flange of the NPA. Passing suction catheters through the NPA can exert considerable force. A safety pin aids you in supporting the airway and prevents its migration into the nasopharynx. Do not place the safety pin through the lumen of the tube, which will prevent insertion of suction catheters into the lumen.

Lubricate the outside of the airway with a water-soluble/aqueous gel (e.g. KY Jelly). Initially, choose the larger nostril that is clear from other tubes (e.g. nasogastric tube). Insert the tip of the NPA into the nostril, then slightly lift the nares up and direct the airway to follow a path along the floor of the nose, parallel to the hard palate. Apply a gentle partial rotation to the NPA if resistance is felt during insertion e.g. from opposition against the turbinates. If this does not relieve the resistance/obstruction then withdraw the airway and try the other nostril before selecting a smaller size. Insert the airway until the flange is resting against the nostril. Being able to gently rotate the airway is an indication that the size is correct.[13]

Sequence showing correct insertion of an NPA

Suction without an NPA

Suction via the nasopharynx can also be performed without the use of a nasopharyngeal airway. This may be preferable in patients who have evidence of secretion retention but where the quantity of secretions may not require frequent suctioning to be performed.

The catheter can be advanced in a similar manner as described above for insertion of a nasopharyngeal airway.

Insertion of a catheter into the nasopharynx involves lifting the nares to reveal the nasal airway and advancing the catheter parallel to the nasal floor.

Considerations and Suctioning Procedure

| Indication | Establish need for airway suction |

| Contraindications | Review the patient’s medical history and identify contraindications and/or precautions to the insertion of an NPA or OPA (See contraindications below)

Seek approval from medical staff prior to insertion/suction via nasopharyngeal or guedel airways |

| Explanation | Explain the procedure to the patient regardless of their alertness.

Obtain consent when able |

| Infection Control | Don gloves, gown, and googles |

| Position | Position the patient in high supported sitting, with head supported in a neutral position |

| Hyper-oxygenate | Hyper-oxygenate the patient if able (increase mask flow rate or FiO2) delivery of 100% oxygen for > 30 secs prior to the suction event |

| Preperation | Prepare for suction procedure

|

| Insert the airway | Insert the NPA or OPA (see instructions above) |

| Assess |

|

| Suction |

|

| Assessment of Outcome |

|

| Hints on suction |

|

| Documentation |

|

Precautions, contraindications, and complications of inserting an OPA or NPA

| Contraindications |

|

| Precautions |

|

| Complications |

|

Clinical Bottom Line

Nasotracheal and orotracheal suction should only be undertaken when other less invasive techniques have proved unsuccessful, and where the secretions are causing physiological deterioration and/or distress[2] Indications that the patients may need suctioning include audible secretions in upper airway or noisy crackles, on auscultation, palpable secretions, ineffective or weak coughing, desaturation despite increased oxygen requirements or raised respiratory rate.

Nasotracheal and orotracheal suction should only be performed by staff who, have been trained and deemed competent as per local policy with relevant training and education being included in an in-service training programme. In addition, opportunities should be offered locally to competent practitioners at all levels wishing to maintain their skills in tracheal suction.

Key Evidence

References

- ↑ 1.01.11.2 Endotracheal Suction Guidelines ICU Working Party, Clinical Interest Group of ISCP

- ↑ 2.02.12.22.3 Pryor JA, Prasad AS. Physiotherapy for respiratory and cardiac problems: adults and paediatrics. 4th edition. Edinburgh : Churchill Livingstone. 2008.

- ↑ 3.03.13.2 American Association for Respiratory Care. Clinical Practice Guidelines: Endotracheal Suctioning of Mechanically Ventilated Patients with Artificial Airways. Respir Care. 2010;55 (6): 758-764

- ↑ Walsh BK, Crotwell DN, Restrepo RD. Capnography/Capnometry during mechanical ventilation. Respiratory care. 2011;56(4):503-509.

- ↑ Argent AC. Endotracheal suctioning is basic intensive care or is it?: Commentary on article by Copnell et al. on page 405. Pediatric research. 2009;66(4):364-367.

- ↑ 6.06.16.2 Carneiri W, Walker A. Adult, Paediatric and Neonatal Airway Suction Policy (All Routes and Methods). St George’s Healthcare NHS Trust. Portex, Kent. 3015; Clin 4.7

- ↑ 7.07.1 Dean B. Evidence-based suction management in accident and emergency: a vital component of airway care. Accident and Emergency Nursing. 1997;5(2):92-8.

- ↑ Carlon GC, Fox SJ, Ackerman NJ. Evaluation of a closed-tracheal suction system. Critical care medicine. 1987;15(5):522-5.

- ↑ 9.09.1 Johnson KL, Kearney PA, Johnson SB, Niblett JB, MacMillan NL, Mcclain RE. Closed versus open endotracheal suctioning: costs and physiologic consequences. Critical care medicine. 1994;22(4):658-66.

- ↑ Subirana M, Solà I, Benito S. Closed tracheal suction systems versus open tracheal suction systems for mechanically ventilated adult patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD004581

- ↑ 11.011.111.211.311.411.511.611.7 Clinical Skills Development Service. Airway Suctioning via the Oropharynx and Nasopharynx. Available from: ↑ Irwin RS, Madison JM, Fraire AE. The cough reflex and its relation to gastroesophageal reflux. The American journal of medicine. 2000;108(4):73-78.

- ↑ 13.013.113.2 GOSH (2014) Nasopharyngeal airway (NPA). Available from: function gtElInit() { var lib = new google.translate.TranslateService(); lib.setCheckVisibility(false); lib.translatePage('en', 'pt', function (progress, done, error) { if (progress == 100 || done || error) { document.getElementById("gt-dt-spinner").style.display = "none"; } }); }