Definition/Description

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN), also known as periarteritis nodosa or Kussmaul-Maier disease, is a serious ideopathic vascular disease that commonly affects both small and medium-sized arteries throughout the body. It falls under the category of primary systemic vasculitis, and more specifically as a necrotizing inflammation without vasculitis of the arterioles, capillaries, or venules.[1] Due to the inflammatory nature of the disease, arteries become swollen and blood flow is diminished.[2] The inflammation, which affects the entire arterial wall, typically manifests where the arteries branch and ultimately the affected vessel tissues become necrotic.[3][4] As the outer and inner layers of the artery swell, blood clots can form and potentially damage various organs and tissues in the body such as the liver, kidneys, heart, GI tract, testes, and muscles.[5]

Prevalence

- Development and diagnosis of the disease seems to occur between the ages of 40 and 60.

- While it affects adults more so than children, it can present at any age.

- Twice as likely to occur in men than women.

- Can affect every ethnicity and race.

- Rare disease, but estimates of frequency in the US are around 77/1,000,000.[6]

- Internationally, reports have listed frequency in south Sweden at 1.6/1,000,000; 4.6/1,000,000 in England; 30.7/1,000,000 in Paris, France.[6][7]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation

Polyarteritis nodosa is clinically similiar to many diseases such as hepatitis B and C infections, Churg-Strauss syndrome, Kawaski disease, hypersensitivity angitis, as well as Cogan’s syndrome.[2] The speed at which the disease affects an individual often varies. Within months, it may initially present with mild symptoms that rapidly progress to fatal symptoms, or it can develop into a chronic state that incapacitates the individual.[3] With the exception of the lungs, polyarteritis nodosa has the ability to affect many organs and organ systems at the same time by damaging the arteries that supply blood flow. The heart, intestines, liver, and kidney arteries are prevalently damaged.[2] Listed below are some of the most common symptoms associated with this disease, affecting the skin, joints, brain, nerves, heart, digestive tract, liver, and kidneys:

- Rashes with raised patches along arteries, discoloration of fingers or toes, blotches that appear purple[3][2]

- Joint pain and inflammation, muscle aches and pain[3][4]

- Fever, headaches, strokes, seizures[3][4]

- Weakness, numbness, tingling, or hand or foot paralysis[3]

- Angina and myocardial infarctions[3]

- Peritonitis (infection of the abdomen), nausea, vomiting, bloody diarrhea, intestinal tears, and rapid weight loss[3]

- Liver damage and failure[3][4]

- Hypertension, edema, decreased output of urine, urine with high levels of protein[3][2]

Associated Co-morbidities

- Cholecystitis

- Pericarditis

- Myocarditis

- Arrhythmias

- GI hemorrhage

- CHF

- Infections

- Hypertension

- Peripheral neuropathies

Medications

Typically corticosteroids and drugs that suppress the immune system are prescribed. One such steroid is [3] If the cause of polyarteritis nodosa is related to a hepatitis infection, and the inflammation has been limited, anti-viral medication along with plasmapheresis is used to combat the infection.[8]

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values[8][3][4][9]

Diagnosis:

Currently there is not a single gold standard test for diagnosing an individual with PAN, rather a cluster of tests and criteria are used to do so. Patient history, blood testing, biopsies from affected sites, and angiograms are all common procedures used to direct the physician with their diagnosis. To further assist with this process, in 1990 the American College of Rheumatology established criteria to help differentiate PAN from other similiar diseases:[9]

1. Weight loss > 4 kg

Loss of 4 kg or more of body weight since illness began, not due to dieting or other factors

2. Livedo reticularis

Mottled reticular pattern over the skin or portions of the extremities or torso

3. Testicular pain or tenderness

Pain or tenderness of the testicles, not due to infection, trauma, or other causes

4. Myalgias, weakness or leg tenderness

Diffuse myalgias (excluding shoulder and hip girdle) or weakness of muscles or tenderness of leg muscles

5. Mononeuropathy or polyneuropathy

Development of mononeuropathy, multiple mononeuropathys, or polyneuropathy

6. Diastolic BP >90 mm Hg

Development of hypertension with diastolic BP higher than 90 mm Hg

7. Elevated BUN or creatinine

Elevation of BUN >40 mg/dl or creatinine >1.5 mg/dl, not due to dehydration or obstruction

8. Hepatitis B virus

Presenece of hepatitis B surface antigen or antibody in serum

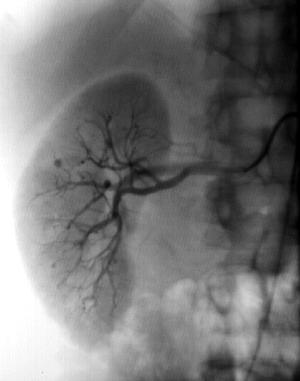

9. Arteriographic abnormality

Arteriogram showing aneurysms or occlusions of the visceral arteries, not due to arteriosclerosis, fibromuscular dysplasia, or other noninflammatory causes

10. Biopsy of small or medium-sized artery containing PMN

Histologic changes showing the presence of granulocytes or granulocytes and mononuclear leukocytes in the artery wall

* For classification purposes, a patient shall be said to have polyarteritis nodosa if at least 3 of these 10 criteria are present. The presence of any 3 or more criteria yields a sensitivity of 82.2% and a specificicy of 86.6%. BP = blood pressure; BUN = blood urea nitrogen; PMN = polymorphonuclear neutrophils.[9]

Lab tests peformed may include:

Etiology/Causes

The cause of PAN remains unknown, but there does appear to be a link to drug reactions, viral infections, and the body’s immune system. Adverse drug reactions to iodide or pencillin, or indiviudals with active hepatitis B or C appear to be at a higher risk for developing this disease.[4] In fact, for approximately every five individuals affected by PAN, one of those people has active hepatitis B.[3]

Due to its involvement with the arterial system, PAN has the ability to affect many systems in the body, notably the nervous, integumentary, renal, and GI system. Listed below are the systems most commonly affected and what is typically seen:

Nervous System:

- Peripheral neuropathy (50-70% of the time) with the individual experiencing numbness, tingling, or burning sensations in the extremities

- CNS lesions

Integumentary System: (most commonly seen affecting the legs)

- Purpura

- Livedo reticularis

- Ulcers

- Nodules

- Gangrene

Renal System:

- Flank pain

- Hypertension

- Decreased kidney function (dialysis may be needed in some cases)

- Protein in urine

Gastrointestinal System:

- GI bleeding

- Abdominal pain

- Nausea/vomiting

- Constipation

- Melena

- Hematochezia

- Possible hemmorrhage or perforation (rare)

Musculoskeletal System:

- Arthralgia

- Myalgia

- Arthritis (less common)

Cardiac System:

- Chest pain

- Tachycardia

- Pericarditis

- Myocarditis

- Arrhythmias

- Dyspnea

- Possible myocardial infarctions or congestive heart failure

Ophthalmologic:

Genitourinary System:

- Testicular pain (unilateral)

- Testicular infarction

Neuropsychiatric:

- Headache

- Depression

- Psychosis

Pulmonary System:

- Involvement of the lungs is very rare

Medical Management (current best evidence)

Medicinal Treatment and Prognosis:

Treatment is neccesary, and corticosteroids ([5][10] However, if the individual is also affected with hepatitis B, treatment becomes much more complex as these medications can make the hepatitis B infection worse. If hepatitis B is present as well, the current thought is to treat the vasculitis for two weeks using prednisone, and then undergo plasmapharesis while addressing the infection using anti-viral therapy with [10]

“5 Factor Score” – The likelihood of mortality is increased should any of the 5 factors listed below be present:[11]

- Involvement of CNS

- Involvement of the GI system (infarction, pancreatitis, bleeding, perforation)

- Cardiomyopathy

- Renal insufficiency (serum creatine >1.58 mg/dL)

- Proteinuria (>1 g/d)

Non-Hepatitis B Virus (non-HBV) related PAN treament with a 5 factor score of 1 or greater:

Non-Hepatitis B Virus (non-HBV) related PAN treatment with a 5 factor score of 0 or greater:

Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) PAN treatment:

- oral prednisolone with or without intravenous methylprednisolone

- plasmopharesis with lamivudine

Surgery:

Medication is the typical treatment for individuals with PAN, however surgery is necessary should the affected individual present with appendicitis, cholecystitis, pancreatitis, infarction of the digestive tract, hemorrhage, or bowel perforation.[12] Poor outcomes are typically seen with these surgeries with the exception of the procedures for appendicitis or cholecystitis, which have outcomes similiar to those not affected by the disease.[12]

Emerging treatments for PAN:[13]

- Use of

Additional Information:

Physical Therapy Management (current best evidence)The current best treatment for PAN primarily consists of medical management with the use of the corticosteroids and immunosuppressant drugs. Patients that present in one’s clinic with the aforementioned signs and symptoms should be referred to their physician. With the nature of the disease, many systems are affected and currently there is no practice pattern for which PAN falls under in the Guide to Physical Therapy Practice (2nd ed.). However, once the patient is medically stable, a physical therapist can help address limitations the individual may be experiencing due to the multiple system involvement. As PAN affects each individual differently, a physical therapist can work with this patient based on their unique needs, and ultimately towards helping them achieve their personal goals and activities of daily living.

Differential Diagnosis[14]

Case Reports/ Case Studies

Resources

References

see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Andrassy K, et al. Nomenclature of systemic vasculitides: proposal of an international consensus conference. Arthritis Rheum.1994;37:187-192.

- ↑ 2.02.12.22.32.4 MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia: polyarteritis nodosa. ↑ 3.003.013.023.033.043.053.063.073.083.093.103.113.12 Merck Manual: polyarteritis nodosa. ↑ 4.04.14.24.34.44.5 Cedars-Sinai: polyarteritis nodosa. ↑ 5.05.15.2 Goodman CC, Fuller KS. Pathology: Implications for the Physical Therapist. 3rd edition. St. Louis, Missouri: Saunders Elsevier, 2009.

- ↑ 6.06.16.2 eMedicine Rheumatology: polyarteritis nodosa. ↑ Mohammad AJ,Jacobsson LT,Mahr AD,et al.Prevalence of Wegener’s granulomatosis, microscopic polyangiitis, polyarteritis nodosa and Churg-Strauss syndrome within a defined population in southern Sweden. Rheumatology 2007;46:1329–1337.

- ↑ 8.08.1 PubMed Health: polyarteritis nodosa. ↑ 9.09.19.2 Lightfoot RW Jr, Michel BA, Bloch DA, Hunder GG, Zvaifler NJ, McShane DJ, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of polyarteritis nodosa. Arthritis Rheum 1990;33:1088-93.

- ↑ 10.010.110.2 Johns Hopkins Vasculitis Center: polyarteritis nodosa. ↑ Guillevin L, Lhote F, Gayraud M, Cohen P, Jarrousse B, Lortholary O. Prognostic factors in polyarteritis nodosa and Churg-Strauss syndrome. A prospective study in 342 patients. Medicine. Jan 1996;75(1):17-28.

- ↑ 12.012.1 Guillevin, L. Treatment of classic polyarteritis nodosa in 1999. Nephrol Dial Transplant.1999;14:2077-2079.

- ↑ BMJ Evidence Centre: emerging treatments for polyarteritis nodosa. ↑ Medscape Reference: polyarteritis nodosa. function gtElInit() { var lib = new google.translate.TranslateService(); lib.setCheckVisibility(false); lib.translatePage('en', 'pt', function (progress, done, error) { if (progress == 100 || done || error) { document.getElementById("gt-dt-spinner").style.display = "none"; } }); }