The Running Gait Cycle

Running is similar to walking in terms of locomotor activity. However, there are key differences. Having the ability to walk does not mean that the individual has the ability to run.[1]

Running requires:

- Greater balance

- Greater muscle strength

- Greater joint range of movement

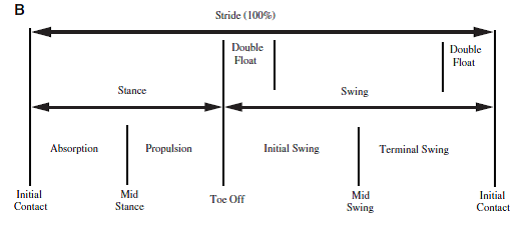

There is a need for greater balance because the double support period present in

The amount of time that the runner spends in float, increases as the runner increases in speed. The muscles must produce greater energy to elevate the head, arms and trunk (HAT) higher than in normal walking, and to support HAT during the gait cycle. The muscles and joints, must also be able to absorb increased amounts of energy to control the weight of HAT.

During the running gait cycle, the Ground reaction force (GRF) at the centre of pressure(COP) have been shown to increase to 250% of the body weight.[2]

A useful article that provides a good overview of running biomechanics can be read here:

Novacheck ’97: The Biomechanics of Running [3]

Joint Motion

- Beginning of stance phase – hip is in about 50° flexion at heel strike, continuing to extend during the rest of the stance phase. It reaches 10° of hyperextension after toe off.

- The hip flexes to 55° flexion in the late swing phase.

- Before the end of the swing phase, the hip extends to 50° to prepare for the heel strike.

- The knee flexes to about 40° as the heel strikes, then flexes to 60° during the loading response

- The knee begins to extend after this, and reaches 40° flexion just before toe-off.

- During swing phase and the initial part of the float period, the knee flexes to reach maximum flexion of 125° during the mid swing.

- The knee then prepares for heel strike by extending to 40°

- The ankle is in about 10° of dorsiflexion when the heel strikes, and then dorsiflexes rapidly to 25° DF.

- Plantarflexion happens almost immediately, continuing throughout the rest of the stance phase of running, and as it enters swing phase also.

- Plantarflexion reaches a maximum of 25° in the first few seconds of of swing phase.

- The ankle then dorsiflexes throughout the swing phase to 10° in the late stage of swing phase, preparing for heel strike.

- The lower limb medially rotates during the swing phase, continuing to medially rotate at heel strike.

- The foot pronates at heelstrike.

- Lateral rotation of the lower limb stance leg begins as the swing leg passes by the stance leg in mid stance position.

Muscle Activity

- Gluteus maximus and gluteus medius are both active at the beginning of stance phase, and also at the end of swing phase.

- TFL is active from the beginning of stance, and also the end of swing phase. It is also active between early and mid swing.

- Adductor Magnus is active for about 25% of cycle, from late stance to early part of swing phase.

- Iliopsoas activity occurs during swing phase for 35-60% of cycle.

- Quadriceps works in an eccentric manner for the initial 10% of the stance phase. Its role is to control knee flexion as the knee goes through rapid flexion. It stops being active after the first part of the stance phase, there is then no activity until the last 20% of swing phase. At this point it becomes concentric in behaviour so it can extend the knee to prepare for heel strike.

- Medial Hamstrings become active at the beginning of the stance phase(18-28% of stance), they are also active throughout much of the swing phase(40-58% of initial swing then the last 20% of swing). They act to extend the hip and control the knee through concentric contraction. in late swing, the hamstrings act eccentrically to control knee extension and take the hip into extension again.

- Gastrocnemius muscle activity starts just after loading at heel strike, remaining active up until 15% of the gait cycle (this is where its activity begins in walking). It then re-starts its activity in the last 15% of the swing phase.

- Tibialis anterior muscle is active through both stance and swing phases in running. It is active for about 73% of the cycle (compared to 54% when walking). The swing phase when running, is 62% of the total gait cycle, compared to 40% when walking, so TA is considerably more active when running. Its activity is mainly concentric or isometric, enabling the foot to clear the support surface during the swing phase of the running gait.

Elastic Support Strategy

Joanne Elphinstone (2013)[4] describes this as a mechanism for transferring force from the lower control zone to the upper control zone and back again.

In runners the diagonal elastic support mechanism is utilised. This is produced by a constant diagonal stretch and release that is enabled by the body’s counter rotation. The force continually flows up and down these force pathways alternately. The pattern of force distribution prevents force being concentrated in one area, but allows wide distribution of force throughout the body.

Elphinsone[4] maintains that it is crucial to have a well functioning central core area to allow this pattern of force distribution to take place efficiently.

Rotation through the Kinetic Chain

The kinetic chain can be described as a series of joint movements, that make up a larger movement. Running mainly uses sagittal movements as the arms and legs move forwards. However, there is also a rotational component as the joints of the leg lock to support the body weight on each side.

There is also an element of counter pelvic rotation as the chest moves forward on the opposite side. This rotation is produced at the spine, and is often referred to as the spinal engine. This is also linked to running economy[4]. This counter rotation enables the spinal forces to be dissipated as the foot hits the ground.

Runners may complain of a feeling of restriction in hamstrings or shoulders, however, when examined it may be found that there is actually limitation in rotation of the pelvis, causing the problem.

Multimedia

References

- ↑ Norkin C; Levangie P; Joint Structure and Function; A comprehensive analysis; 2nd;’92; Davis Company.

- ↑ Mann RA: Biomechanics of running. In D’ Ambrosia, RD and Drez D: Prevention and treatment of running injuries, ed 2. Slack, New Jersey, 1989

- ↑ Novacheck TF; The Biomechanics of running; Gait and Posture 7; 1998; 77-95

- ↑ 4.04.14.2 Elphinsone J; Stability, sport and performance movement 2nd ed; 2013; Lotus Publishing. pg 19.