Description

Morton’s Neuroma (MN) is a condition associated with the common plantar digital nerves, caused by entrapment of the nerve and repetitive traction underneath the deep transverse metatarsal ligament leading to epineural and perineural fibrous overgrowth[1]

Also known as Morton neuroma, Morton’s metatarsalgia, Intermetatarsal neuroma and Intermetatarsal space neuroma[2], the benign neuroma or perineural neuroma[3] most commonly affects the intermetatarsal plantar nerve of the second and third intermetatarsal spaces (between 2nd−3rd and 3rd−4th metatarsal heads), which results in the entrapment of the affected nerve.

The main symptoms are pain and/or numbness, sometimes relieved by removing footwear.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

The plantar aspect of the forefoot. Particularly the intermetatarsal spaces. The common digital nerve and its branches in the third planter webspace are often affected[4].

Mechanism of Injury

Some sources claim that entrapment of the plantar nerve because of compression between the metatarsal heads, as originally proposed by Durlacher and later Morton[5], is highly unlikely, because the plantar nerve is on the plantar side of the transverse metatarsal ligament and thus does not come in contact with the metatarsal heads. It is more likely that the transverse metatarsal ligament is the cause of the entrapment.[6][7]

Epidemiology

The onset of MN is usually between 45 and 50 years of age with women affected much more than men[8]. Pain onset is often insidious. However neuromas can be present without clinical signs. One study reported neuromas present in 33% (19/57)[8] of asymptomatic individuals.

Aetiology

Altered foot and ankle biomechanics such calf tightness, planovalgus or varus deformities play a role in overloading the foot, leading to altered pressure on the third and fourth rays and associated pain[3].

Clinical Presentation

Symptoms include pain on weight bearing, frequently after only a short time. The nature of the pain varies widely among individuals. Some people experience shooting pain affecting the contiguous halves of two toes. Others describe a feeling like having a pebble in their shoe[3] or walking on razor blades. Burning, numbness, and paresthesia may also be experienced.[9] The symptoms progress over time, often beginning as a tingling sensation in the ball of the foot (Mulder’s Sign).[10]

Morton’s neuroma lesions have been found using MRI in patients without symptoms.[8]

Diagnostic Procedures

Clinical diagnosis can be up to 99% accurate with typical complaints of plantar webspace pain, paraesthesias and/or numbness aggravated by weight-bearing activities and eased by rest and massage[1].

Clinical Examination

There is often no obvious deformity, erythema, sign of inflammation, or limitation of movement. Direct pressure between the metatarsal heads will replicate the symptoms, as will compression of the forefoot between the finger and thumb so as to compress the transverse arch of the foot.

Both legs below the knee should be observed, The plantar aspect of the foot in question should be observed and palpated for callouses, foot position (loaded and unloaded). The patient can also point to the area of pain.[3] Circulation and sensation should also be assessed. Muscle function, in particular calf muscle tightness should be assessed. This can be done using Silfverskioldt’s test[3].

A history and description of the forefoot pain and its onset should be taken, noting any aggravating and easing factors. Gait analysis could reproduce the forefoot pain as well as manifest gait changes. Footwear should also be observed for wear and tightness.

In a 2019 review[3] of MN diagnosis and management, Gougoulias et al suggest the following to make a potential diagnosis of MN:

- Web-spaced tenderness test

- Squeeze test (Mulder’s click)

- Plantar percussion test – a postive Tinel sign

- Toe-tip numbness

See Histopathology

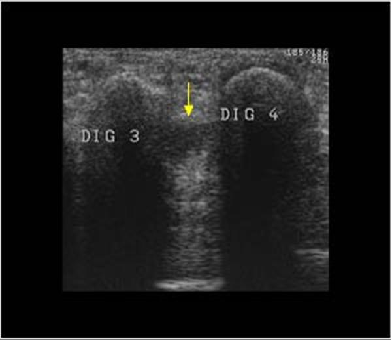

Microscopically, the affected nerve is markedly distorted, with extensive concentric perineural fibrosis. The arterioles are thickened and occlusion by thrombi are occasionally present.[11] Though a neuroma is a soft tissue abnormality and will not be visualized on standard radiographs, the first step in the assessment of forefoot pain is an X-ray in order to evaluate for the presence of arthritis and exclude stress fractures/reactions and focal bone lesions, which may mimic the symptoms of a neuroma. Ultrasound (sonography) accurately demonstrates thickening of the interdigital nerve within the web space of greater than 3mm, diagnostic of a Morton’s neuroma. This typically occurs at the level of the intermetatarsal ligament. Frequently, intermetatarsal bursitis coexists with the diagnosis. Other conditions that may also be visualized with ultrasound and can be clinically confused with a neuroma include synovitis/capsulitis from the adjacent metatarsophalangeal joint, stress fractures/reaction, and plantar plate disruption.[12][13] MRI can similarly demonstrate the above conditions; however, in the setting where more than one abnormality coexists, ultrasound has the added advantage of determining which may be the source of the patient’s pain by applying direct pressure with the probe. Further to this, ultrasound can be used to guide treatment such as cortisone injections into the webspace, as well as alcohol ablation of the nerve.

There are other causes of pain in the forefoot. Too often all forefoot pain is categorized as neuroma[3]. Other conditions to consider are capsulitis, which is an inflammation of ligaments that surrounds two bones, at the level of the joint. In this case, it would be the ligaments that attach the phalanx (bone of the toe) to the metatarsal bone. Inflammation from this condition will put pressure on an otherwise healthy nerve and give neuroma-type symptoms. Additionally, an intermetatarsal bursitis between the third and fourth metatarsal bones will also give neuroma-type symptoms because it too puts pressure on the nerve. Freiberg’s disease, which is an osteochondritis of the metatarsal head, causes pain on weight bearing or compression.

Rest and massage[14], footwear and activity modification are the first line of conservative treatment.

Manual therapy has been shown to be effective for pain resolution of symptoms,[1] however there is little evidence to support this. Manual therapy is hypothesized to alter afferent nociceptive barrages, normalize sensori-motor mismatches, activate descending anti-nociceptive pathways. [15] Therefore, utilizing manual therapy in case of pain seems appropriate.[1] Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy has been shown to be a potentially useful modality to reduce pain in patients with Morton’s neuroma[16].

Treatment often involves corticosteroid injections and surgical excision however, these approaches do not guarantee complete relief[1]. Recently, an increasing number of procedures are being performed at specialist centers which offer a range of procedures to treat Morton’s neuroma under ultrasound guidance. Recent studies have shown excellent results for the treatment of Morton’s neuroma with ultrasound guided sclerosing alcohol injections,[17] ultrasound guided radiofrequency ablation, and ultrasound guided cryo-ablation.[18] Ultrasound can be used to minister the injection on the exact location of the neuroma. By using direct in-plane approach, the needle is visualized during the whole injection.[19] These are widely used conservative treatments for Morton’s neuroma. In addition to traditional orthotic arch supports, a small foam or fabric pad may be positioned under the space between the two affected metatarsals, immediately behind the bone ends. This pad helps to splay the metatarsal bones and create more space for the nerve so as to relieve pressure and irritation. It may however also elicit mild uncomfortable sensations of its own, such as the feeling of having an awkward object under one’s foot. Corticosteroid injections can relieve inflammation in some patients and help to end the symptoms. For some patients, however, the inflammation and pain recur after some weeks or months, and corticosteroids can only be used a limited number of times because they cause progressive degeneration of ligamentous and tendinous tissues.

These are an increasingly available treatment alternative if the above management approaches fail. Dilute alcohol (4%) is injected directly into the area of the neuroma, causing toxicity to the fibrous nerve tissue. Frequently, treatment must be performed 2–4 times, with 1–3 weeks between interventions. A 60-80% success rate has been achieved in clinical studies, equal to or exceeding the success rate for surgical neurectomy with fewer risks and less significant recovery. If done with more concentrated alcohol under ultrasound guidance, the success rate is considerably higher and fewer repeat procedures are needed.[20] Is also used in the treatment of Morton’s Neuroma.[21] The outcomes appear to be equally or more reliable than alcohol injections especially if the procedure is done under ultrasound guidance.[22] If such interventions fail, patients are commonly offered surgery known as neurectomy, which involves removing the affected piece of nerve tissue. Postoperative scar tissue formation (known as stump neuroma) can occur in approximately 20%-30% of cases, causing a return of neuroma symptoms.[23] Neurectomy can be performed using one of two general methods. Making the incision from the dorsal side (the top of the foot) is the more common method but requires cutting the deep transverse metatarsal ligament that connects the 3rd and 4th metatarsals in order to access the nerve beneath it. This results in exaggerated postoperative splaying of the 3rd and 4th digits (toes) due to the loss of the supporting ligamentous structure. This has aesthetic concerns for some patients and possible though unquantified long-term implications for foot structure and health. Alternatively, making the incision from the ventral side (the sole of the foot) allows more direct access to the affected nerve without cutting other structures. However, this approach requires a greater post-operative recovery time where the patient must avoid weight bearing on the affected foot because the ventral aspect of the foot is more highly enervated and impacted by pressure when standing. It also has an increased risk that scar tissue will form in a location that causes ongoing pain.

This is a lesser known alternative to neurectomy surgery. Cryogenic neuroablation (also known as cryo injection therapy, cryoneurolysis, cryosurgery or cryoablation) is a term that is used to describe the destruction of axons to prevent them from carrying painful impulses. This is accomplished by making a small incision (~3 mm) and inserting a cryoneedle that applies extremely low temperatures of between −50 °C to −70 °C to the nerve/neuroma.[24] This results in degeneration of the intracellular elements, axons, and myelin sheath (which houses the neuroma) with wallerian degeneration. The epineurium and perineurium remain intact, thus preventing the formation of stump neuroma. The preservation of these structures differentiates cryogenic neuroablation from surgical excision and neurolytic agents such as alcohol. An initial study showed that cryo neuroablation is initially equal in effectiveness to surgery but does not have the risk of stump neuroma formation.[25]Imaging

Differential Diagnosis

Management

Physiotherapy Intervention

Medical Intervention

Orthotics and Corticosteroid Injections

Sclerosing Alcohol Injections

Radio Frequency Ablation

Neurectomy

Cryogenic Neuroablation

References

(http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1356689X08000593)

Keywords: Fibromyalgia; Central sensitisation; Whiplash; Chronic fatigue syndrome

Sule Sahin Onat, MD, Ayse Merve Ata, MD, and Levent Ozcakar, MD.