Definition/Description

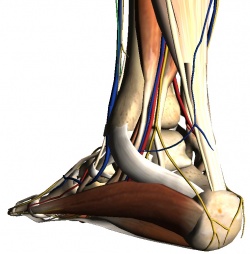

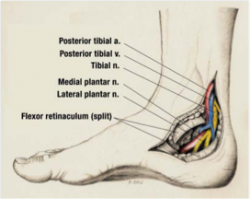

The tarsal tunnel is a channel between the medial malleolus, talus, calcaneus and the flexor retinaculum – a fibrous sheet that runs from the medial malleolus to the calcaneus. The tunnel contains[1][2]:

- Tibialis posterior tendon

- Flexor digitorum longus tendon

- Posterior tibial artery & vein

- Tibial nerve (yellow in image)

- Flexor hallucis longus tendon

The tibial nerve divides into two terminal branches – the medial and lateral plantar nerves – as it passes through the tarsal tunnel. The medial calcaneal nerve branches from the tibial nerve at or superior to the flexor retinaculum. [4][5][6]

Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome (TTS) is a rare compressive neuropathy of the tibial nerve or one of its branches as they pass under the flexor retinaculum.[6][7][2][8][9]

In the TTS literature, the tibial nerve is also referred to as the posterior tibial nerve and TTS is also known as Posterior Tibial Nerve Neuralgia[7]. Some authors [10][4] refer to compression of the deep fibular nerve as “anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome”. This page is limited to the discussion of tarsal tunnel syndrome as the entrapment of the posterior tibial nerve or its branches.

Epidemiology/Etiology

Incidence is unknown[2][8][11]. A higher prevalence is reported for women than men[2][8][9]. It can be seen at any age.[8] Causes of TTS include[7][2][8][12][4][9][13]:

- Repetitive stress activities such as running, excessive walking or standing

- Traumas such as fracture, dislocation or stretch injuries

- Heel varus or valgus

- Fibrosis

- Excessive Weight

- Space occupying lesions in tarsal tunnel region such as a ganglion, tumors, edema, osteophytes or varicosities

- Tendonitis

- Systemic diseases that cause ankle inflammation or nerve compromise (ex: diabetes mellitus, arthritis)

Many cases (20%-40%) are idiopathic.[2][4]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation

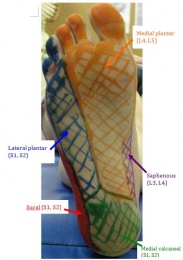

Common symptoms of TTS include paresthesia (burning, numbness or tingling) in the posterior tibial, lateral plantar and/or medial plantar nerve distributions – see picture. Burning, tingling, or pain in the medial portion of the ankle and or plantar aspect of the foot, as well as local tenderness behind the medial malleolus may be seen[14][6][15]. Symptoms usually worsen with forced eversion and dorsiflexion of foot. When the medial plantar nerve is affected in isolation patients can present with stabbing pain in the medial sole of the foot upon walking, which is usually seen in middle aged runners. In a progressed or chronic case muscle weakness of the toe abductors and flexors can be demonstrated. In more serious cases muscle atrophy can be seen[4]. Patients can also present with night pain that awakens them from sleep as well as aggravation with prolonged walking[11].

Differential Diagnosis

TTS can present similarly to other lower extremity conditions with the most common differential diagnosis being plantar fasciitis as these patients also present with plantar heel pain[5]. In addition to Plantar fasciitis (in which TTS is thought to be commonly misdiagnosed as), polyneuropathy, L5 and S1 nerve root syndromes, Morton metatarsalgia, compartment syndrome of the deep flexor compartment will have to be distinguished from tarsal tunnel syndrome as well[4].

Outcome Measures

Foot and Ankle Ability Measure (FAAM)

- The FAAM is a reliable, responsive, and valid measure of physical function for individuals with a broad range of musculoskeletal disorders of the lower leg, foot, and ankle.[16]

Rating Scale for the Severity of Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome [17]

| Absent | Some | Definite | |

| Pain, spontaneous or on movement | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Burning pain | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Tinel’s sign | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Sensory disturbances | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Muscle atrophy or weakness | 2 | 1 | 0 |

Examination

It is important to take a thorough history. The physical therapist should inquire about the following:[18]

- Mechanism of injury (MOI) – was there any trauma, strain, or overuse?

- Duration and location of pain and parathesia?

- Weakness or difficulty walking?

- Back or buttock pain associated with more distal symptoms?

- Pain getting worse, staying the same, or getting better?

Key history Findings:

- Parathesia or burning sensation in the territory of the distal branches of the tibial nerve

- Prolonged walking or standing often exacerbates patient’s pain

- Dysesthesia (an abnormal and unpleasant sensation) arises during the night and can disturb sleep

- Weakness of muscles

Observation (observe in weight bearing and non-weight bearing):

- Muscle atrophy of the abductor hallucis muscle may be seen

- Check for arch stability

- Position of the talus and calcaneous

Gait Analysis:

- Assess for abnormalities (excessive pronation/supination, toe out, excessive inversion/eversion, antalgic gait, etc.)

Sensory Testing

- Test light touch, 2-point discrimination, and pinprick in the lower extremity

- Deficits will be in the distribution of the posterior tibial nerve

Palpation:

- Tender to palpation in between the medial malleolus and Achilles tendon

- Painful in 60-100% of those affected[4]

Range of Motion (ROM):

- Focus on ankle and toe ROM

Manual Muscle Testing (MMT):

- Decreased strength generally occurs late in the progression of TTS

- The phalangeal abductors are impacted first followed by the short-phalangeal flexors

Special Tests:

Tinel’s Sign:

- Percussion of the tarsal tunnel results in distal radiation of parathesias

- Elicited in over 50% of those affected [4]

Dorsiflexion – Eversion Test: [14]

- Place the patient’s foot into full dorsiflexion and eversion and hold for 5-10 seconds[18]

- The results are that it elicits the patient’s symptoms

EMG studies: [11]

- The presence of an isolated tibial nerve lesion in the tarsal tunnel is confirmed by measurement of the sensory and motor nerve conduction velocity (NCV).

- Sensory conduction velocity of the medial and lateral plantar nerves. This is best done by recording from the tibial nerve just above the flexor retinaculum and stimulating the nerves at the vault of the foot. When surface electrodes are used, the responses to stimulation are of low amplitude.

- Measurement of the motor NCV through recording of the distal motor latency at the abductor hallucis brevis muscle is a much easier, but less sensitive method. The important finding on electromyography (EMG) is the demonstration of axonal injury when the EMG is recorded from the distal muscles supplied by the tibial nerve.

Medical Management

PHARMACOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT

Pharmacological treatments are often used in combination with physical therapy management to optimize recovery and decrease functional disability.[2][4][18]

- NSAIDS

- Corticosteroid Injections

- Pain Medications

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Surgery is indicated for patients who have not benefited from conservative treatments such as physical therapy and have symptoms that significantly impact their daily life. Individuals with a space occupying lesion tend to not to respond to conservative management and often require surgery. Godges and Klingman have identified several characteristics that have been associated with a successful response to surgery. The charateristics include; younger age, short history of symptoms, no previous history of ankle pathology, early diagnosis, and a determined etiology.

- Posterior Tibial Nerve Decompression[19]

– If there is a space occupying lesion, the lesion will be removed

and decompression will not be done. - Cryosurgery[20]

ALTERNATIVE MANAGEMENT

Physical Therapy Management

There is a lack of high level evidence concerning physical therapy management for tarsal tunnel syndrome. Further research is needed to identify specific rehabilitation exercises for patients with tarsal tunnel syndrome. Small randomized controlled trials would help analyze the effectiveness of specific treatments.[2][4]

CONSERVATIVE MANAGEMENT[22][23]

| Physical Agents | Orthotics | Therapeutic Ex | Manual Therapy | |

| Acute Stage Goal: reduce pain and swelling |

-Ice -Pulsed ultrasound -Phonophoresis -E-stim |

-Ankle bracing -CAM walker -Plantar arch taping -Medial heel wedge -Pt edu on footwear |

-Calf stretching -Nerve mobility |

-Soft tissue massage -Tibial nerve mobilization |

| Subacute Stage Goal: increase flexibility and STR |

-See above | -See above | -Posterior tibialis strengthening |

-See above |

| Settled Stage Goal: promote symmetrical flexibility, STR, and functional mobility |

-See above | -See above | -Posterior tibialis strengthening in WB |

-See above |

One of the mechanical causes of tarsal tunnel syndrome is believed to be excessive calcaneal eversion leading to collapse of the medial longitudinal arch (over pronation) which puts traction stress on the posterior tibial nerve and compression by the flexor retinaculum. Scherer proposes that custom fit orthoses will correct the over pronation and therefore decrease the stress on the posterior tibial nerve. Although there is no clinical outcome studies documenting the effectiveness of orthotics, it may be an important technique to consider when treating patients with tarsal tunnel syndrome.[24]

Several articles listed basic techniques for conservative management of tarsal tunnel syndrome as a guideline to rehabilitation, but did not provide patient outcomes.[2][25][4][12]

POSTOPERATIVE TREATMENT[26]

| Timeframe | Goals | Intervention | |

| Phase I | 1-3 wks | -Protect nerve, joint, and incision site -Control swelling -Reduce pn |

-Immobilization with NWB precautions -Ankle passive ROM -RICE -Gait training with AD |

| Phase II | 3-6 wks | -Prevent contractures -Prevent scar tissue adhesions -Increase joint mobility |

-WBAT -Gentle passive and active ankle stretching -Begin tibial nerve glide with anti-tension technique (foot PF and inverted) -Gait training to tolerance with protective splint -Aquatic therapy |

| Phase III | 6-12 wks | -Normal gait mechanics -Increase ankle mobility -Increase PF strength -Specific skill development |

-Gait training without splint -Pain free theraband exercises -Tibial nerve glide progression (foot everted and dorsiflexed) -Weight bearing exercises -Resistive exercises (impairment approach) -Balance/proprioceptive training -Specific skill development in pain free range -Cardiovascular fitness |

CASE STUDIES

Romani et al reported their findings for a 22 year old male lacrosse player experiencing tarsal tunnel syndrome. The player experienced a mild eversion ankle sprain that was successfully managed with conservative treatment. Upon a second eversion ankle sprain, the patient made an executive decision to participate in the NCAA tournament causing aggravation of symptoms ultimately leading to surgical repair. Within a 13 week rehabiliatation program, treatment consisted of RICE, ROM, balance, theraband exercises, aquatic therapy, and walking which was eventually progressed to running. At the end of 13 weeks, the athlete returned to intercollegiate lacrosse participating at an elite level. For specific postsurgical protocol, click the following link.[25]

Dr. Karen Hudes conducted a single subject case study addressing a conservative approach to treating tarsal tunnel syndrome. The 61 year old patient with diagnosed tarsal tunnel syndrome reported pain and discomfort along the medial ankle with a Verbal Rating Scale of 9/10. Initial management included orthotics for the first ten weeks after which the patient reported little to no change in her symptoms. After unsuccessful outcomes with orthotics, treatment techniques such as cross friction massage, HVLA toggle board adjustments of the talonavicular joint, and mobilizations of the cuboid were used twice per week. The patient’s symptoms began to decrease at 3 weeks, resolved by 6 weeks with low pain intermittent recurrences, and completely resolved within 12 weeks. The patient reported no pain at a ten month follow up.[2]

Key Research

Resources

Clinical Bottom Line

There is a lack of high quality research on effective management of tarsal tunnel syndrome. The physical therapist should stage the patient based on swelling, pain, duration of symptoms and/or time since surgery. Management should be impairment based to address specific strength, flexibility, gait and functional limitations of a given patient.

References